Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Similar to Friedrich Nietzsche, Vazha-Pshavela (ვაჟა-ფშაველა) was born into a family of priests. The same as the German philosopher, the Georgian also developed a radical critical stance towards traditional, ancestral values that were often clad in religiosity and sanctity – to the point of arriving at the existential crisis of perceiving life as valueless and fundamentally futile. Indeed, Vazha (as he is simply referred to among Georgians) places himself in front of the abyss of perceiving all of reality as vanity. Whereas Nietzsche’s crisis ends with the deaths of metaphysics, truth and God, as his drastic opposite, Vazha-Pshavela’s similar crisis culminates in the re-acquisition of Christianity, which becomes not a blindly followed tradition of ancestors, but a personal living experience of the Light of God; of a rebirth in this Light.

_ვაჟა-ფშაველას_პორტრეტი.jpg)

Portrait of Vazha-Pshavela

Vazha-Pshavela is a patently European thinker, deeply entrenched in the tradition of the Enlightenment – with its demand for individual intellectual activity and daring to think for oneself, unaided by authority. He became exposed to this tradition in an academic setting at Gori Spiritual Seminary, where he engaged in a lively student life that, besides the regular classes, entailed animated discussions and debates about literature and philosophy. In one such debate Vazha-Pshavela, at that time only a 19-year-old student named Luka Razikashvili, successfully defended the cause for famous Russian thinker Vissarion Belinsky, whom he identified as a radical Hegelian, contrary to his opponent who described him as a conservative Hegelian. This shows Vazha-Pshavela’s deep interest in Western philosophical thought already at a young age. He also attended courses at the best academia available at that time – St Petersburg University, for a period of one year but could not continue due to lack of money.

His adherence to the European Enlightenment is at the same time adherence to the search for truth and meaning, for the true dignity of human life, true Christianity. In fact, Christianity claims to be universal, and surely the leitmotif of the Gospel is that it debunks parochial, limited understandings of the Holy Scripture, according to them an unlimited, universal dimension. For example, a human temptation is to reduce the concept of “neighbor” to merely a member of one’s clan or nation, with the exclusion of all others; but the Lord Jesus Christ gives a commandment that explodes any such limited notion: when answering the question of a Pharisee who wanted to justify himself for not loving non-Jews, “Who is my neighbor?” Christ answered in this way: “Every person you do good to is your neighbor.” This sentence leaves any man hearing it responsible and answerable for not making any of the men he encounters his neighbor. Yet how many times in Christian cultures was the eternal dimension abandoned and the infinity of the Christian message confined to human, limited aims, when those aims were announced as sacrosanct and indispensable to Christianity itself. Thus at all times, in every epoch there is a need for inspired heroes who would rescue the universality of the Christian message from human propensities to limit it for political or ideological reasons.

Vazha-Pshavela was such an inspired hero. In his time, Georgia was a part of the Russian Empire, which tried to merge Christianity with the Imperial agenda, with a doctrine that whatever benefited the Orthodox Empire was good and God-pleasing and vice-versa. Vazha-Pshavela would have none of it. For him, the Empire often oppressed human freedom and dignity for its aims, and how could this be the will of God? When after the quashing of a rebellion of Dagestanis, the Russian Empire built a church in celebration of this suppression near Vazha-Pshavela’s village, he drew a target on the white wall of the church and began to train himself by shooting at it – a symbolic act to express his outrage at the hypocrisy of all that: how indeed could God wish to suppress the struggle for freedom of a conquered and oppressed people? Was not the same impulse guiding him when, beside himself with anger, he beat a local priest who, having procured legal documents through his corrupt connections, had tried to deprive the children of their school playground and attach it to his church? Vazha-Pshavela was then a young teacher at the school. The thing he could not stand was when truth was violated by someone in a position of serving truth.

Portrait of Vazha- Pshavela in front of the balcony. Chargali

Vazha- Pshavela with his family

Vazha-Pshavela spent the major part of his life in Chargali, the village he was born in. But he was very active in literary and public life. He worked as a correspondent for a number of newspapers and magazines, writing prolifically on ethnographic, social and political issues. Being a younger representative of the ‘Tergdaleulni’ – a socio political movement that sought to establish Georgia’s autonomy within the Russian Empire, with the aim of laying the foundation for complete independence in the future – he wrote in the spirit of Ilia Chavchavadze, praising the values of Christianity, European Enlightenment and national sovereignty. However, his talent shone most of all in the fields of poetry and prose. Vazha-Pshavela’s philosophical epic-poems have one leitmotif: we as human beings are to be born a second time through our experience of truth, beauty and dignity. This is not easy, however, since a man desiring to grant himself such a rebirth collides with the members of his society, who perceive in him the danger of overturning those stagnated values in which they locate their own identity and dignity. One of the constituents of such identity and dignity can be the image of an enemy: having an enemy and a history of fighting them is a strong cohesive power for a society. The enemy is less human, less loved by God – if at all.

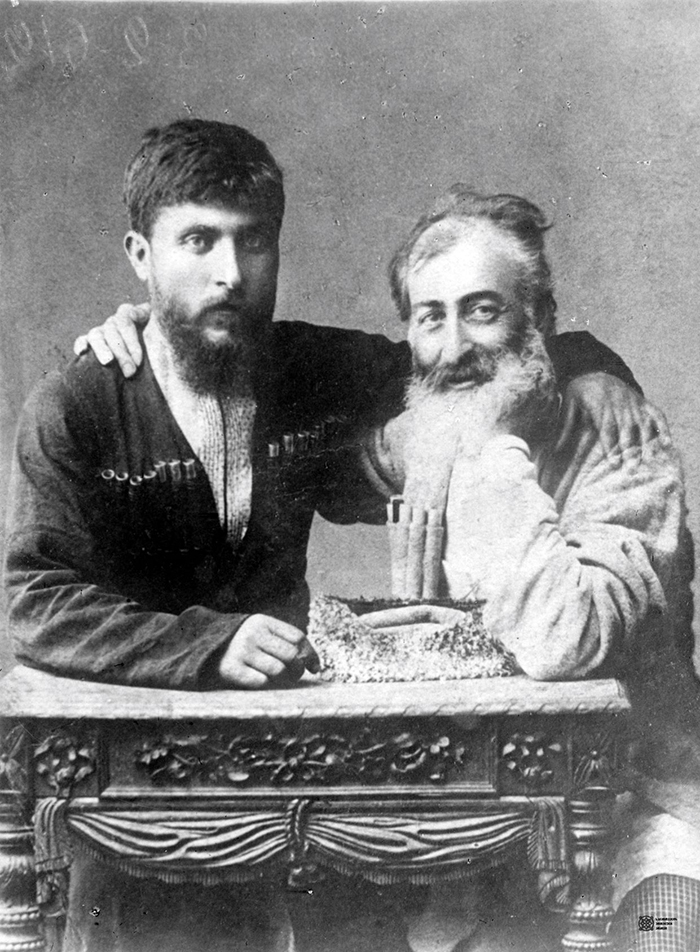

Vazha-Pshavela and Alexander Kazbegi.

Vazha-Pshavela’s personages go beyond this: they experience and respect human dignity fully, even in their enemies. Following the logic of truth they become enemies of their own people, who become an obstacle to this logic. Such are Vazha-Pshavela’s main characters – Aluda Ketelauri, Jokhola Alkhastaidze and his wife Aghaza, or the Elder Lukhumi. Beyond nominal religious affiliations – Christian or Muslim – these heroes see the beauty of universal human dignity, perceiving and respecting it in each other. Far from being schematic and dry, these poems enable the reader to experience real drama, to become participants in it. Vazha-Pshavela does not advocate universalism and cosmopolitanism to the detriment of patriotism, though. As he emphatically claims in his famous essay “Cosmopolitanism and Patriotism,” a true cosmopolitan is also a true patriot of his country, for unless one loves one’s own country and traditions, it is impossible to love the entire world, since such a love will only be an intellectual concept, not a “thing of the heart.” Each nation can attain the universal level through the best achievements of its culture, but also maintain its uniqueness. “Shakespeare” – writes Vazha – “is a true Englishman, and without ceasing to be so, he is also the treasure of all mankind.” He bitterly attacked Marxist cosmopolitans in Georgia, who heralded and celebrated the imminent abolition of nations under one cosmopolitan union of the working class.

Vazha-Pshavela’s short stories, in which he often personifies trees and rocks, rivers, plants and animals, are imbibed by Georgian children from as early as kindergarten; however, they are not at all simply children’s stories, but deeply philosophical and psychological. In one of them, a little rivulet has an apocalyptic nightmare: it has dried up and can no longer give water to the poor animals that come to it to drink. The rivulet wakes up in a cold sweat. That was a fear of Vazha-Pshavela’s own, as he writes in one of his short poems: “What a pity if a poet is deprived of grace!” He knew the torment of being abandoned by Inspiration, which he metaphorically called “eagle.” “Eagle has abandoned me!” – he laments in one of his poems; “I am happy only when a fire is burning inside me!” – he writes elsewhere. He was a true mystic, coveting and longing to experience the presence of God inside him. However, this mysticism had a great social value for Vazha-Pshavela, since he wanted by virtue of the divine grace gushing forth from his poems and stories to irrigate the aridness and futility of life among society, to heal its evils and ills: “I was standing on the top of a mountain,//The whole world spread beneath me,//The sun and the moon have found rest on my chest,//And I spoke with God.//The ills and troubles of the world were my care,//And I desired to live and die for the sake of the world.” However, when divine presence leaves a man, he becomes like a “useless rag.”

._1861-1915._ვაჟა-ფშაველას_პორტრეტი_(ფაფახით).1861-1915წწ..jpg)

Poertrait of Vazha-Pshavela (with Caucasian hat - papakha)

As mentioned at the beginning, Vazha-Pshavela lived through an existential crisis. He reaches a point when the spectre of death and annihilation, and therefore of the futility of everything – of all values, stands invincibly before him, personified by a demon sneering and laughing at him. Even this demon extracts a confession from Vazha-Pshavela: “Yes, I know that death will annihilate all and that all is futile, but love, hatred, inspiration, fight to overcome this thought of death and futility” – he cries back to the demon; and then a mystical vision appears: an elderly figure in a luminous white garment raises his staff and expels the demon, directing Vazha-Pshavela’s gaze towards the eternal Sun that always shines but does not burn, saying to him: “You are a believer, and remain always!” He stood in front of the abyss, having been rescued from it through his unshakeable belief that “it is impossible for the beautiful essence of a human being to be lost,” but this beautiful essence is always in peril, always in need of being rescued from the abyss of evil and futility. Perhaps this caveat and alarm resounds in the metaphor with which Vazha-Pshavela ends one of his epic poems: “Pirimze (a beautiful flower) gazes down at the abyss, with its neck bent gracefully.” (“და უფსკრულს დასცქერს პირიმზე, მოღერებულის ყელითა“).