Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili is one of the most outstanding architects, whose creative work has left a significant mark on Georgia, particularly in Tbilisi. Alexi-Meskhishvili was destined to work during a very interesting time period. He obtained his architectural education in Georgia (1933-1939), at the then Faculty of Construction at the Georgian Polytechnical Institute named after Kirov.

Two significant changes occurred in the field of Soviet architecture during the period when Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili studied and worked - the introduction of socialist realism (the 1930s), which supported designing national features and often directly pushed for decorativeness; and later, the USSR resolution "On the Elimination of Excesses in Design and Construction" (1955), which developed speedy and economical industrial construction while creating the basis for simplicity and strict forms of expression, therefore banning all those decorative elements that distinguished the architecture of the former period.

After returning from the Second World War, Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili worked first as an architect, then as a chief architect at "Sakshakhtproekti" (Georgian mining project) until 1958. Accordingly, he worked actively in the regions of Georgia (Martkopi, Tkvarcheli, and Tkibuli), though we can only make a picture of this period of his work based on sketches.

Club, Tkibuli, 1940s. Sketch on tracing paper. L. Alexi-Meskhishvili family archive

Of all the projects created by Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili during the period of Socialist Realism, only the Sanatorium "Imereti" in Tskaltubo (1948-1961) has been preserved (architects: Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili and Levan Janelidze, with the participation of Tinatin Paniashvili; structural engineer: M. Tsentebadze). The building clearly conveys the trends of the time while also taking into account the function of the building and adapting it to the landscape as much as possible. A three-story white-stone building in classical style standing on a hill completely fits the requirements of the prevailing architectural style at the time; monumentality and decorative elements are its distinguishing traits. In his sketches, which are typical of the Stalinist style, we see more extensive adornment with archivolts and balustrades than the existing building displays. Rather than using ornamental features, it seems that the authors were attempting to make an impression using a variety of shapes.

Sanatorium “Imereti”, Tskaltubo, 1950s. Sketch on tracing paper. L. Alexi-Meskhishvili family archive

Though Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili had to work in two completely different stylistic and ideological periods, all of his works are characterized by their simplicity, subtlety, and lack of excessive decoration and overload of details. Even though his projects share some common features, they are all unique. No two buildings are the same; they represent the logical continuation of his creative trajectory. Aside from making the building functionally convenient and well-organized, the architect strives with his projects to consider the environment and existing landscape, adapt to them, and avoid over-invading them.This quality is typical not only for projects designed in the regions but also for those designed to be built in Tbilisi.

From 1958 on until the end of his life, Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili worked at "Tbilkalakproekti", Tbilisi’s main design organization from 1938 to 1991, where general urban plans of the capital were worked out as well as the projects for important buildings and micro-districts were created and developed. In the beginning, he served as the chief architect of the project and later headed the third architectural studio. A number of distinguished buildings, which have left an indelible mark on the city’s appearance, were designed in the creative environment of this studio.

The third architectural studio of “Tbilkalakproekti”, Tbilisi, 28.01.1969

Sitting (from left to right): Vitaly Zhitkovsky, Temur Mikashavidze, Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili, Kiazo Nakhutsrishvili

Standing (from left to right): Germane Ghudushauri, unknown, Zurab Karamurza, unknown, unknown, Keta Kobakhidze, unknown, Guram Mebuke, unknown. Photograph from the T. Mikashavidze family archive.

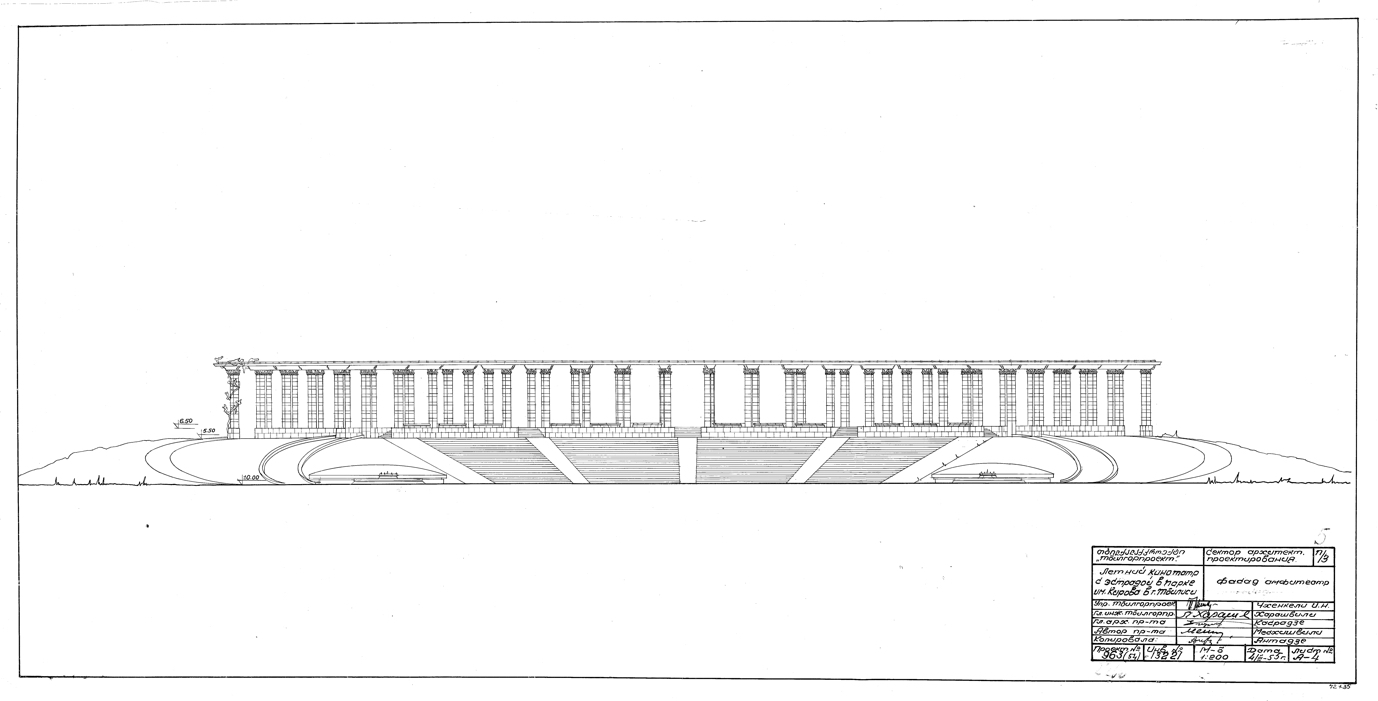

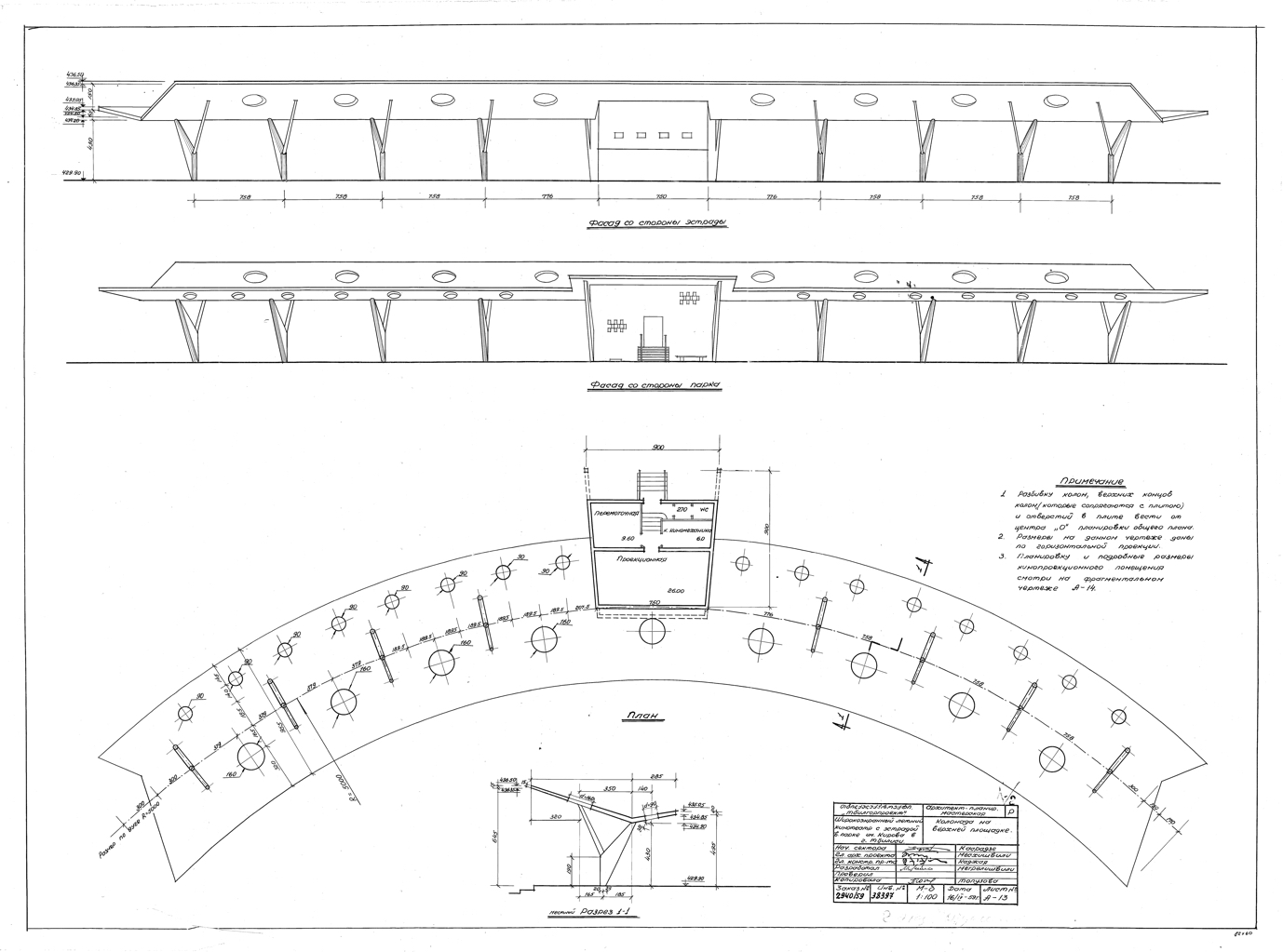

An Outdoor Cinema, the Sports Palace, and the restaurant "Iori" are those projects that clearly illustrate the transitional stage between the two periods mentioned above, with their architectural forms gradually refining and becoming lighter. Following the Sports Palace and an Outdoor Cinema, none of the projects feature the columns and arches that are typical of Stalinist architecture. The round shape (the Sports Palace and "Iori") is continually revealed; however, the spherical roof was later replaced by a flat roof, while inner courtyards and open areas appeared (the Central Telegraph, Parking Garage, and the Agricultural Institute).

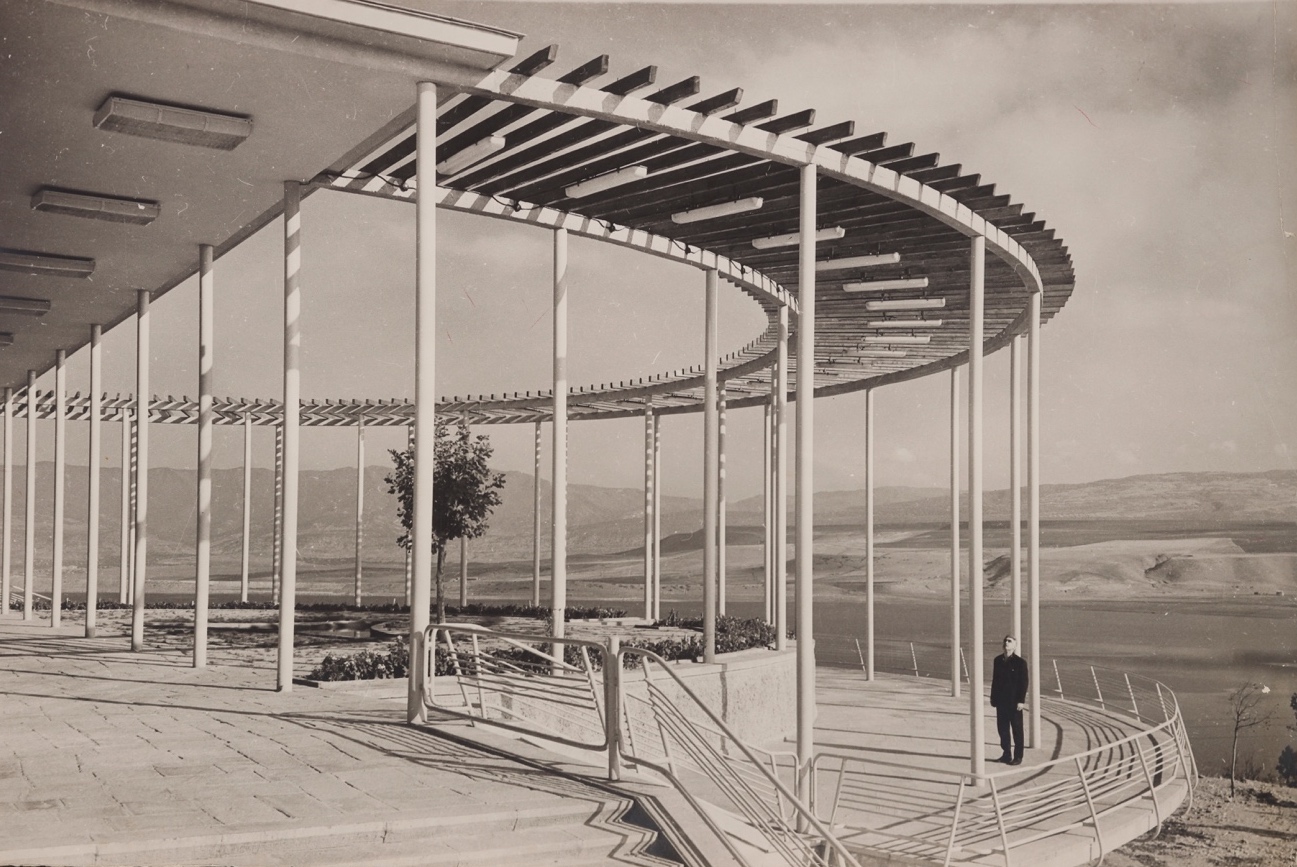

Outdoor Cinema, amphitheater facade, 1955. National Archives of Georgia, Central Archive of Contemporary History

Colonnade, 1959. National Archives of Georgia, Central Archive of Contemporary History

Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili on the veranda of the restaurant “Iori”, 1962.L. Alexi-Meskhishvili family archive

The Tbilisi Sports Palace (1956-1961, architects: Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili and Yuri Kasradze; structural engineer: Davit Kajaia) is exceptionally noteworthy. The building is located in the depths of the site, allowing for the perception of the structure on the one hand and for the free dispersion of the movement of streams of spectators on the other. Unfortunately, this effect is now lost against the backdrop of legal and illegal constructions that have occurred in the area over the years.The exterior of the building is exceptionally minimal. Modest architectural forms can be found on the facade, with the main motif of a strong, five-arched arcade with archivolts surrounding the building as a deep passage from its three sides. A continuous horizontal three-row strip of windows that begins above the arches and ends in the eaves contributes to the sense of lightness and elegance.In the interior, this glazed gallery is flooded with air and light and is directly connected to nature outside.

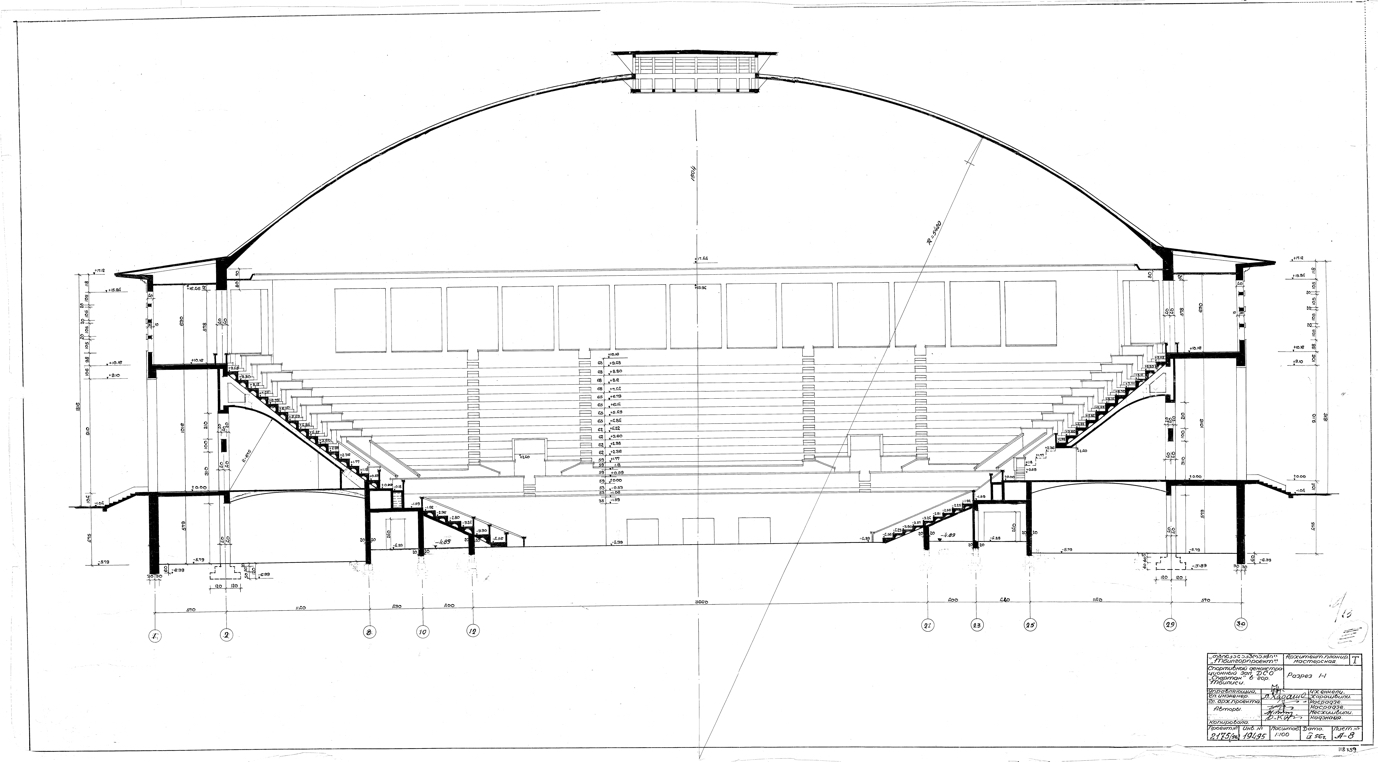

Visitors can enter the hall from three sides through 33 doors. By passing through a comparatively small foyer, the audience enters an unexpectedly large hall. The building is sunken about 15 meters below ground level. Such a design solution contributes to the fact that the actual size of the building is not perceived from the outside; in reality, only the two above-ground floors are visible.

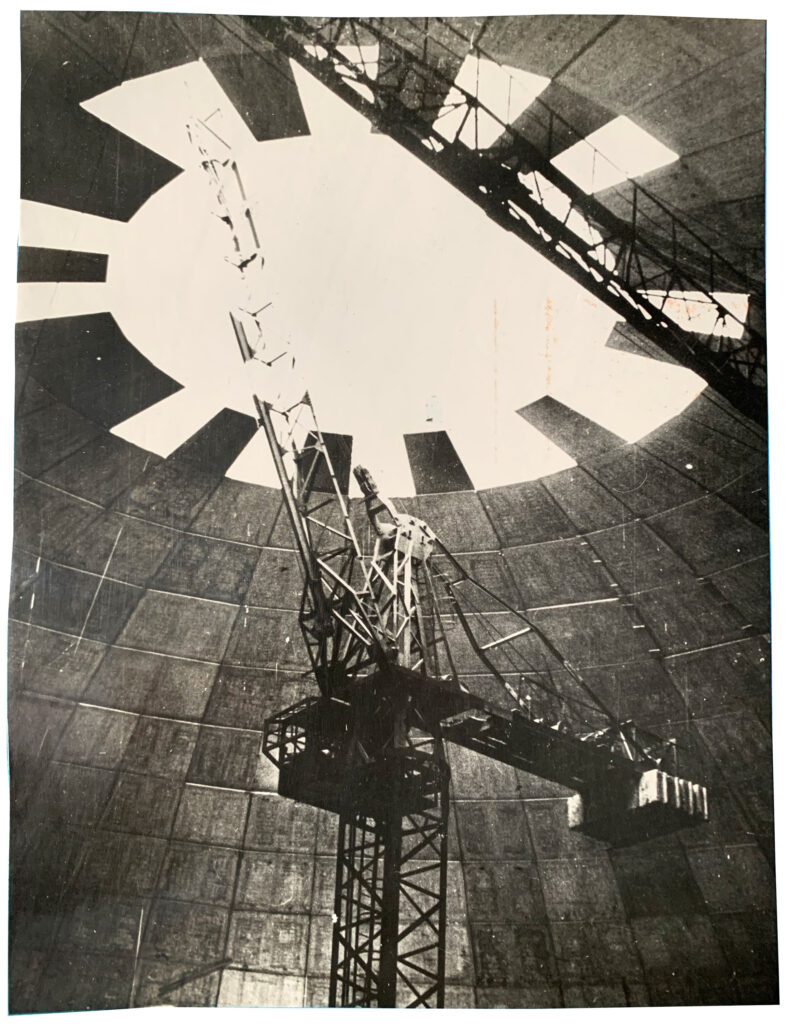

The 76x76-meter hall is covered with a thin, sloping precast concrete dome membrane, which was erected without any supporting structures and was totally unique at that time. The roof slabs are aligned in ten concentric circles, with the diameter of the circles gradually decreasing from bottom to top. Simultaneously, the quantity and size of slabs decrease. Each cell has a segment for the placement of reinforced concrete slabs. Engineer Davit Kajaia obtained the copyright for the design of this roof as well as its method of installation.

Tbilisi Sports Palace, cross section drawing, 1956. National Archives of Georgia, Central Archive of Contemporary History

Tbilisi Sports Palace, the process of assembling the roof, 1960. D. Kajaia family archive

The Parking Garage of the Council of Ministers of the Georgian SSR in Tbilisi (1963–1970) was no less remarkable. The architects were Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili and Gia Kurdiani, and the structural engineer was Guram Mebuke. It was originally built in the Ortachala district, and soon an identical version was repeated in the district of Krtsanisi. Due to the limited ground area and uneven terrain, the authors decided to give the building a cylindrical shape with an open inner courtyard. It was a flat-roofed precast monolithic reinforced concrete structure.The building had seven stories and was divided into zones for different purposes. On the bottom floor, there were rooms for daily maintenance, the entrance/exit, and workshops. A colonnaded veranda encircled almost the entire floor, which combined administrative and housekeeping rooms. The upper floors served as parking spaces for both buses and cars. From the side of the inner courtyard, three stairwells and an emergency lift with a 2-vehicle capacity were attached. The façade of the building was very simple and reflected the structure of the building. Following the horizontally divided, continuously glazed tiers of the building, the windows wrapped the entire volume like a belt and provided natural light.

Unfortunately, these buildings were unable to withstand market demands. Nowadays, when there is such an urgent need for parking lots, this project could have served as an example; nevertheless, both parking garages were demolished to make way for the more profitable projects of private investors.

Parking Garage of the Council of Ministers, Tbilisi, 1970. G. Kurdiani family archive

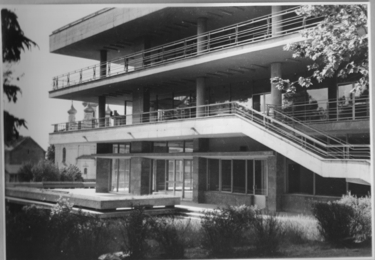

The Tbilisi Chess Palace and Alpine Club building (1965-1973) turned out to have a more fortunate destiny. The architects were Lado Alexi-Meshkhishvili and Germane Ghudushauri, the structural engineer was Guram Mebuke, and the artists were the "Sameuli" creative collective: Alexander Slovinski, Oleg Kochakidze, and Yuri Chikvaidze. As the name suggests, this building that was intended for two types of sports was not especially large and does not dominate the surrounding area. The layout of the floors follows the terrain and is organically inscribed in the park environment. The structure has two stories on the west side and three stories on the east. The Eklar Stone façade is simple and restrained; it is a play of horizontal lines. The façade of the building is mostly comprised of ribbon windows and doors, which give the structure a feeling of lightness while also making it easy to achieve natural lighting and ventilation.

Tbilisi Chess Palace and Alpine Club, northern façade, 1974. G. Ghudushauri family archive

The main hall, which can accommodate up to 520 people, is the focal point of the structure. A very interesting and innovative decision was made regarding an additional lighting system as well as to increase the number of attendees in the hall. The hall is surrounded by side galleries on the third floor, which are separated by six mobile panels. If necessary, these panels may be raised higher, enabling more people to watch the games while also allowing natural light to enter the central hall of the building.

Tbilisi Chess Palace and Alpine Club, main hall, 1974. G. Ghudushauri family archive

The material and technique used in the wooden marquetry of the panels deserve a special mention. Since this technique was uncommon in Georgia and is still not widely used.It serves as a thoughtful parallel to a chessboard veneer.

This building has a strong conceptual connection to the game of chess. The stone vitrage on the west façade of the building is a stylized version of a queen's crown, which supports the assertion that the structure was dedicated to a queen. The railing details bear even more stylized versions of this design. Such in-depth consideration and methodology are now quite rare in the fields of architecture, art, and urban planning.

The building continues to serve its original purpose, but parts of it are rented out to various tenants in order to generate additional income. Unfortunately, owing to the lack of maintenance regulations strictly enforced by the law, the building's original appearance has been altered, mostly because all the tenants have modified the spaces to suit their needs.

A conservation and adaptation plan was developed for the Chess Palace and Alpine Club building between 2018 and 2020, initiated by the Georgian National Committee of the Blue Shield and with financial support from the Getty Foundation's "Keeping it Modern" program. The full document was submitted to the Tbilisi Municipality City Hall, the building's current owner. The works required in order to return the building to its original appearance have not yet been undertaken.

Lado Alexi-Meskhishvili paid special attention to the location and its connection, which he maintained in all of his projects. All the buildings in his sketches are related to nature; they take into consideration a mountain ridge, a slope, or a seashore. One of the leading motifs in his sketches is a "House on the Mountain." The family archive contains numerous sketches that illustrate different variations on this theme: horizontally distributed houses on a mountain ridge, then the same houses are raised in height and represent a continuation of the ridge, and finally they are crowned in the form of towers. In all these cases, the architectural forms of traditional Georgian residential houses—whether it be a Darbazi or Bani (dome or flat roof) type house or the towers typical of mountainous regions—can be clearly read.

Sketches of unrealised projects. L. Alexi-Meskhishvili family archive

Sketches of unrealized projects. L. Alexi-Meskhishvili family archive

Sketches of unrealized projects. L. Alexi-Meskhishvili family archive

Sketches of unrealized projects. L. Alexi-Meskhishvili family archive

It is impossible to summarize and describe all the buildings in one article; the list of buildings he designed but which, for various reasons, were not realized is extremely long. Nevertheless, based on the family archive, we can conclude that the architectural map of Georgia would have been even richer with his remarkable projects.