Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Ilia Chavchavadze was born in 1837. At that time, Georgia had already ceased to exist as a political entity, not with even a minimal degree of sovereignty. By the manifesto of 1801 of Alexander I, the Kingdom of Kartli -Kakheti officially joined the Russian Empire. Soon, the Kingdom of Imereti fell to the same fate. The territory of Georgia was divided into two administrative units – the Tbilisi and Kutaisi governorates. After the suppression of the rebellions against the Russian Empire, and especially the fiasco of the conspiracy of 1832, many believed that Georgia's political future had already been permanently ceded to Russia, and the only thing Georgians could save was their cultural and ethnic identity within the boundaries of that vast empire. Georgia also ceased to exist as a future political project, and the leitmotif of Georgian society became sadness and regret, caused by the passing of the fate of the Motherland into other hands, and a fact well reflected in Georgian literature. Nikoloz Baratashvili wrote a poem about just this, titled "Bedi Kartlisa" (“The Fate of Kartli”). Other writers and poets openly or covertly spoke about it: "The one who came from afar to my estate directs my life," wrote Aleksandre Chavchavadze in one of his poems. Another Georgian poet, Grigol Orbeliani, also expressed a desperate dream - his longing for a hero who would liberate Georgia from Russia: “Where is that hero who with a mighty voice will wake up Georgia’s sleeping fate; who will vanquish the dragon in one blow of a sword in his right hand?!”. Despite these dramatic perceptions, there was also a positive view and understanding of the new situation. Georgians gained stability and peace within the borders of the empire. It was possible to use this situation in the national interests, for national consolidation, this being vitally important when the Russification policy promised the country full cultural and political absorption. In these conditions, Georgians of different backgrounds and titles showed a completely new level of solidarity, which was necessary to preserve the national face and identity. Georgians also saw the Russian Empire as a kind of window to Europe during this period. From the best Russian universities, Georgian thinkers learned about European culture and returned to Georgia with fresh and progressive ideas. The school for nobility established by Solomon Dodashvili, which became a center of European education, was clear proof of this.

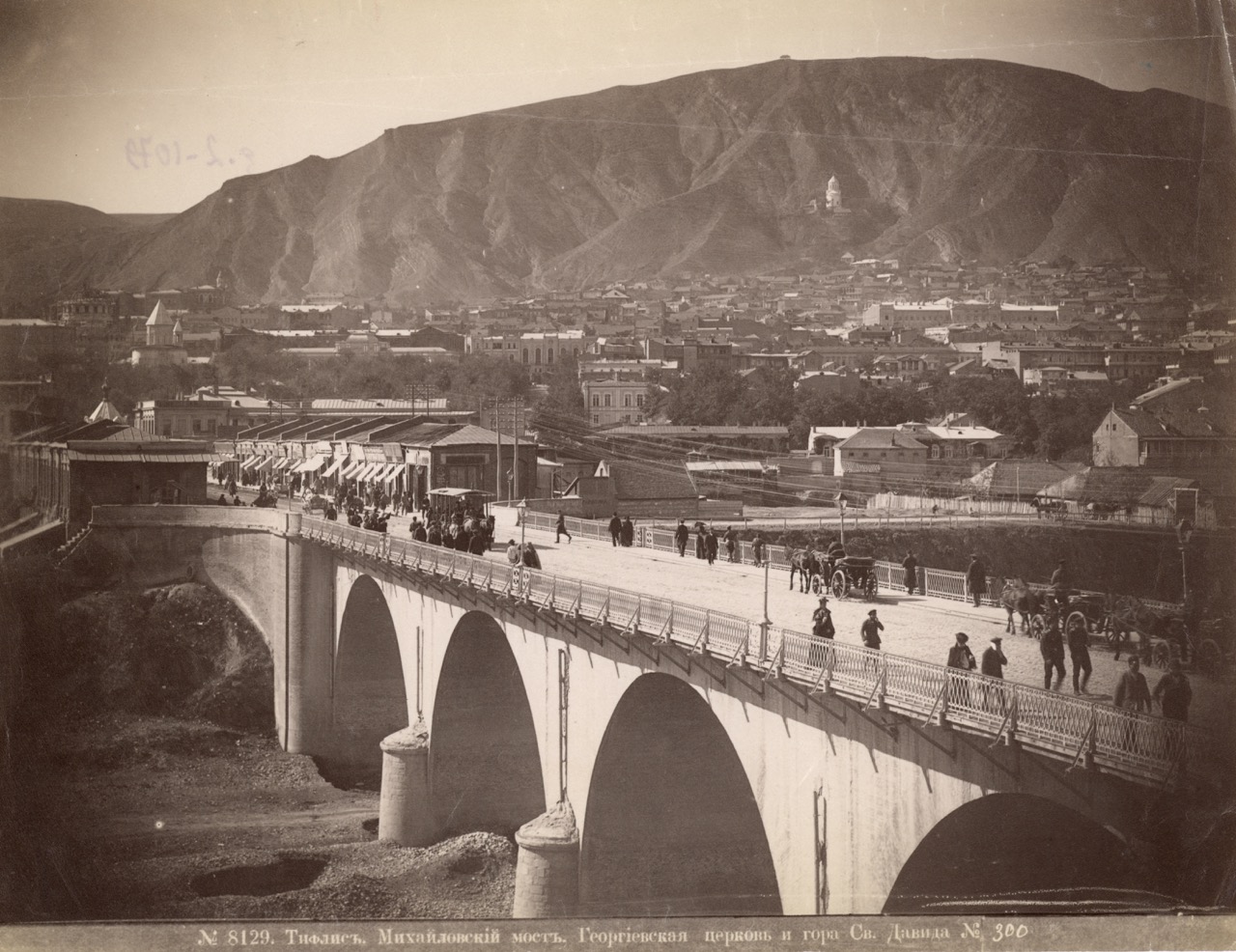

Georgia,Tbilisi in XIX century

In this reality Ilia Chavchavadze appeared on the Georgian literary arena. Ilia wished to develop and strengthen all national cultural initiatives that had previously existed in Georgia. He also wanted to create a political project for Georgia that would set the country's future political goal - to achieve political self-determination and become a nation-state, that is, to join the general European trend, where various small nations like Ireland, Hungary, or what was to become Czechoslovakia, and others, faced the same objective of self-determination under the pressure of empires. Ilia was the leader of the founders of the new movement called "Tergdaleulebi." All the members of the movement, Iakob Gogebashvili and Akaki Tsereteli among them, had received a European education in Russia and, figuratively speaking, had "drunk water of the Tergi," that is, they had crossed the River Tergi (Terek).

_Large.jpeg)

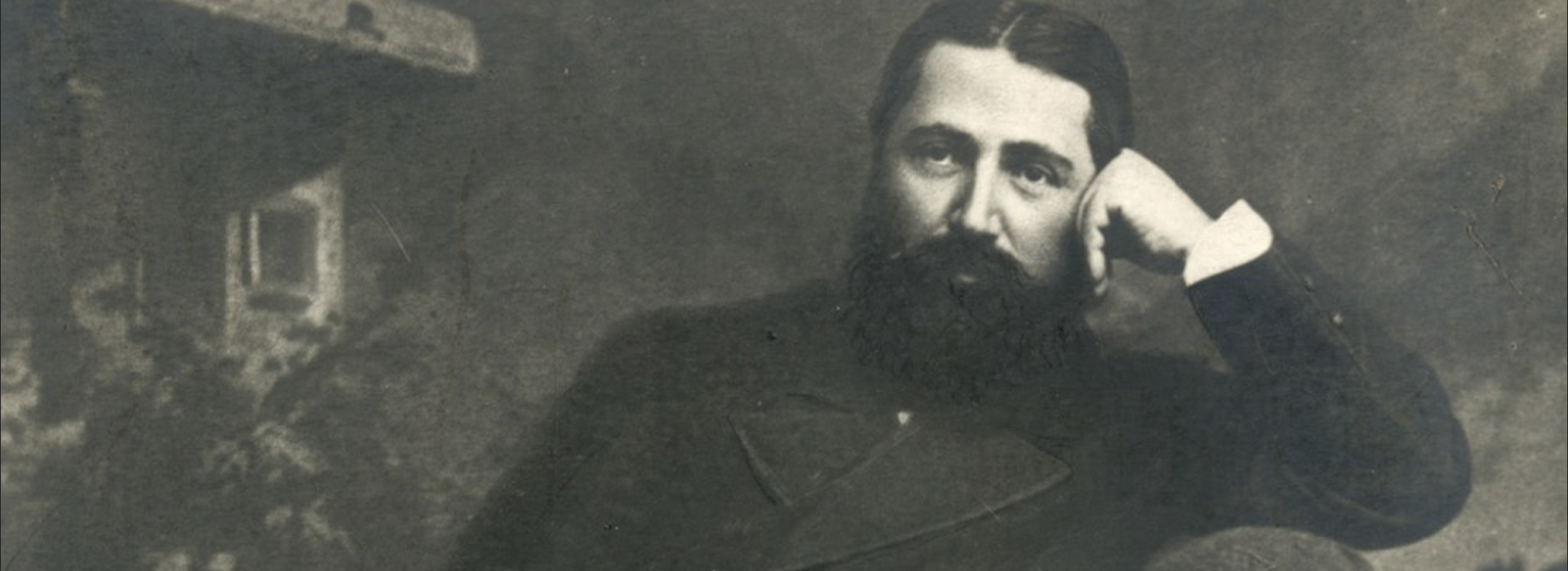

Ilia Chavchavadze (1837 - 1907)

Ilia completed his legal education at St. Petersburg University Faculty of Law, and upon his return, served as a magistrate judge for a time. In parallel, he took up journalism, challenging the entire Georgian intellectual elite to a duel with his first letter “A few words about Revaz Eristavi's translation of 'The Mad Girl' by Kozlov." In addition to the fact that it was a sharp satire on the low quality translation of a rather poor literary work, the 24-year-old Ilia already expressed in this letter his future mission: First, in the article, he didn’t use the common literary language, which was understandable only to the elite due to archaisms and artificiality; instead, he used a more popular and accessible form of Georgian, which became the basis of Ilia’s language reform - establishing a common vocabulary for journalistic writing that was comprehensible to Georgians of different backgrounds. He was sure that without it, national consolidation would not be possible. Second, Ilia stood in stark contrast to the helpless and immature psychotype of the protagonist of Kozlov's poem, and took as an example the active, Byronic psychotype characteristic of European enlightenment, in the spirit of "sapere aude" - a person who trusts in his destiny rather than the assistance of others; taking it bravely in his hands, he tries to discover the meaning of life by exploring and taking chances on his own. According to Ilia, a new, European-Georgian psychotype was needed - in order to form a new Georgia and take the reins of national destiny into their own hands, Georgians had to become personally courageous and free so as to implement the political project of national freedom.

This was the aim of Ilia's entire work. In addition to creating a new literary style of Georgian language that was understandable to Georgians from all social classes and places, he accomplished a remarkable feat in coining new words and terms that were essential to his contemporary intellectual reasoning. Using this new language, Ilia launched the newspaper ‘Iveria.’ Prior to that, he had founded the magazine ‘Georgian Moambe’ (which the government outlawed due to the word "Georgia" in the title, which had separatist overtones to the imperial censors). Iveria aimed to bring all Georgians together around a single, unifying concept: Georgia's future autonomy and ultimate independence. Ilia envisaged the country's final political freedom from a century-long perspective, and was not in favor of a revolutionary course, preferring instead an evolutionary path.

One of the Ilia’s most significant undertakings, achieved together with other progressive representatives of his rank, was the establishment of the National Bank. Ilia was the head of this bank for some time, and even spent several months in St. Petersburg studying banking. The bank was to economically assist the nobility, who represented the spiritual-intellectual elite of Georgia, and at the same time, to finance projects of national scale and importance, such as the Society for the Spreading of Literacy among Georgians, the National Theater, etc. Since we have mentioned theater, let us also note how much Ilia valued Georgian theater, frequently attending performances, methodically criticizing them in letters, and even taking on roles himself, such as the role of Kent in "King Lear."

Saint-Petersburg XIX century

At the same time, Ilia purposefully sought to connect the centuries-old culture and identity of Georgia, built on the Christian faith, with Europe and the global sociopolitical and cultural developments that came from Europe. Many of these changes, in Ilia’s opinion, were part of a divine plan in the history of mankind, and hence were necessarily acceptable; among them were such providential changes as labor liberation, women's emancipation, the gradual removal of rank barriers, and the recognition of a person's personal dignity to be acknowledged not on the basis of his rank, but on the basis of his service and contribution to society. His stories, novels, poems, as well as his journalistic writings, address these major problems. For example, in the novella Is That a Man?!, Ilia creates a caricature image of a Georgian noblemen through a personage Luarsab. Luarsab is unable to grasp the course of history or the irreversible changes that are taking place around him; he sees no need for transformation or new approaches, and blindly adheres to the old and archaic ways, making thus a laughinstock out of himself and leaving himself futureless. On the contrary, in the novella Otaraant Widow, Ilia depicts a new, progressive Georgian nobelman, Archil, who recognizes that the old ways are no longer practical, since they are detached from real life and contemporary historical challenges, and as such are no longer justifiable neither from a practical nor from a moral perspective. For example, Archil believes Giorgi, the central character of the novella, died as a result of his, Archil’s entanglement with the traditional status limits; that Giorgi’s dignity was diminished just because he was of a peasant origin. Archil's sister, Keso, was unaware of or rather refused even to notice, to say nothing about to accept, the possibility that Giorgi dared to fall in love with her. At the end of the story, Archil expresses his optimism that this gap between ranks can be bridged by mutual understanding and the force of human, Christian compassion.

_handwriting__Large.jpeg)

Ilia Chavchavadze's handwriting

_Large.jpeg)

Ilia Chavchavadze (1837 - 1907)

Ilia viewed Christianity in a new light. He believed that Christianity should be much more effectively linked to sociopolitical tasks; it was not enough to think about eternity and salvation of one’s soul; it was inadequate and crippling for Christianity to leave secular space to the dominion of evil and flee from it for personal salvation. This core principle is depicted in possibly Ilia's most powerful work The Hermit, in which the monk eventually dies because he understands too late that it was incorrect to entirely equate the secular space with evil, and for that reason to completely separate from it. This discovery becomes so obsessive that the monk cannot stand it and dies. Ilia believed that Christianity should be associated with national issues, such as the preservation of the national image, national political tasks, and the desire to "make ourselves belong to ourselves,” i.e. gain political independence. One of Ilia's most famous slogans "Homeland, Mother tongue, Faith” indicates exactly that. In his words, these are the three divine treasures that we inherit from our forefathers, and it is our Christian duty to take care of them. This does not mean, however, that Ilia considered only Christians to be Georgians. In his letter which refers to those Georgians who converted to Islam during their time living in the Ottoman Empire, who then entered the Russian Empire after the Russo-Turkish War, Ilia condemns the foolish attempts to convert them to Christianity quickly and harshly. On the contrary, he emphasizes their true Georgianness and linguistic and historical ties with other Georgians. Indeed, according to Ilia, muslim Georgians were often more patriotic and more civically active than their fellow Christians, and thus behaved more christianly.

_Large_2.jpeg)

Ilia Chavchavadze (1837 - 1907)

In his final years, Georgian Marxists resisted Ilia's national-political objectives, which encouraged Georgians of all ranks- nobility, peasants, merchants and workers, to be in solidarity with each other for the common Georgian cause. This was unacceptable from the Marxist perspective of class struggle. A number of Ilia's publicist letters of those last years of his life are dedicated to the polemics of the Georgian dogmatist Marxists. Marxism became so popular, especially among Georgian youth, that many of them openly welcomed Ilia's assassination, because, from their perspective, Ilia hampered the Marxist dialectic of history in Georgia by calling for peace and solidarity between ranks, instead of inciting class conflict. The popular assumption that the murder of Ilia was planned by the representatives of the radical wing of the Social Democrats may be completely true. In any case, the latter's dirty and slanderous journalistic campaign against Ilia provides the basis for this.

Ilia was assassinated in 1907 when he was about to depart from Georgia to S. Petersburg to deliver a speech at the State Duma. Ironically, this speech addressed the elimination of the death sentence throughout the Russian Empire. He believed that no one has the right to take the life of others, criminals included, as life was given to them by God. It is also noteworthy that, until the Bolshevik government arrived in 1921, no one was executed in Tbilisi following the publication of Ilia's novella "On the Gibbet," in which this exact idea is conveyed.

Ilia Chavchavadze was canonized by the Church of Georgia in 1987. Ilia's work and ideas are as relevant and modern today as they were during his lifetime, since Georgians' self-perception as carriers of centuries-old Christian culture and awareness of European enlightenment, which is still a leitmotif for their national identity, is largely based on and nourished by Ilia's works and ideas.