Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Akaki Tsereteli is unquestionably Georgia’s most beloved poet of the people. Indeed, he is known and loved more deeply than any other poet in the country. This extraordinary popularity stems from both his character and deep regard for his people, and, most importantly, from the uniqueness of his work. Tsereteli was a poet who was open, honest, simple, compassionate, and occasionally self-deprecating; who never shone the spotlight on himself; who used poetic forms that were popular and easy to understand; who creatively understood what people were saying; who skillfully adapted metaphors and idioms to fit the context; and who ruthlessly exposed political and social vices and human weaknesses through his creations. Tsereteli’s inexplicably profound compassion for the misery of his fellow citizens succeeded in piquing not only the interest of his contemporary society, but that of future generations too.

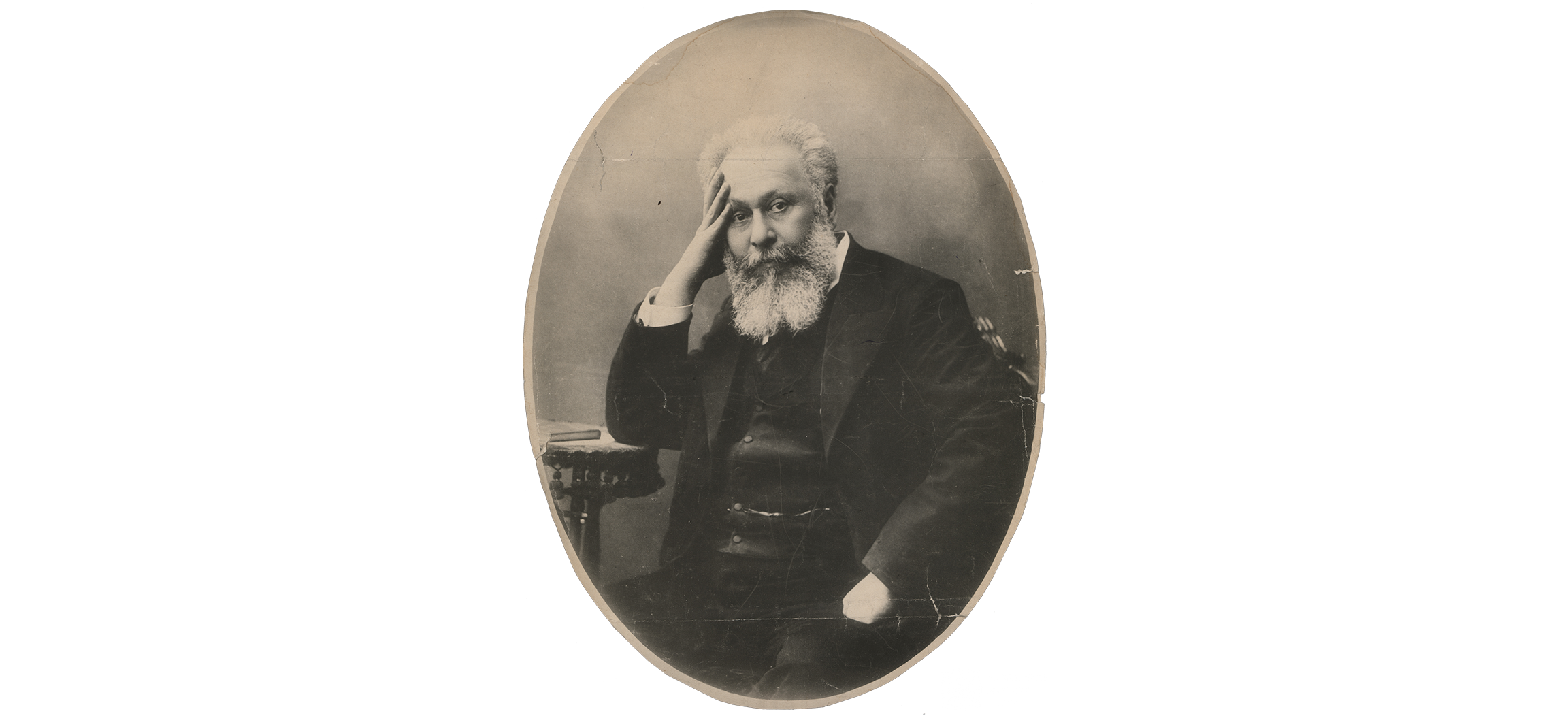

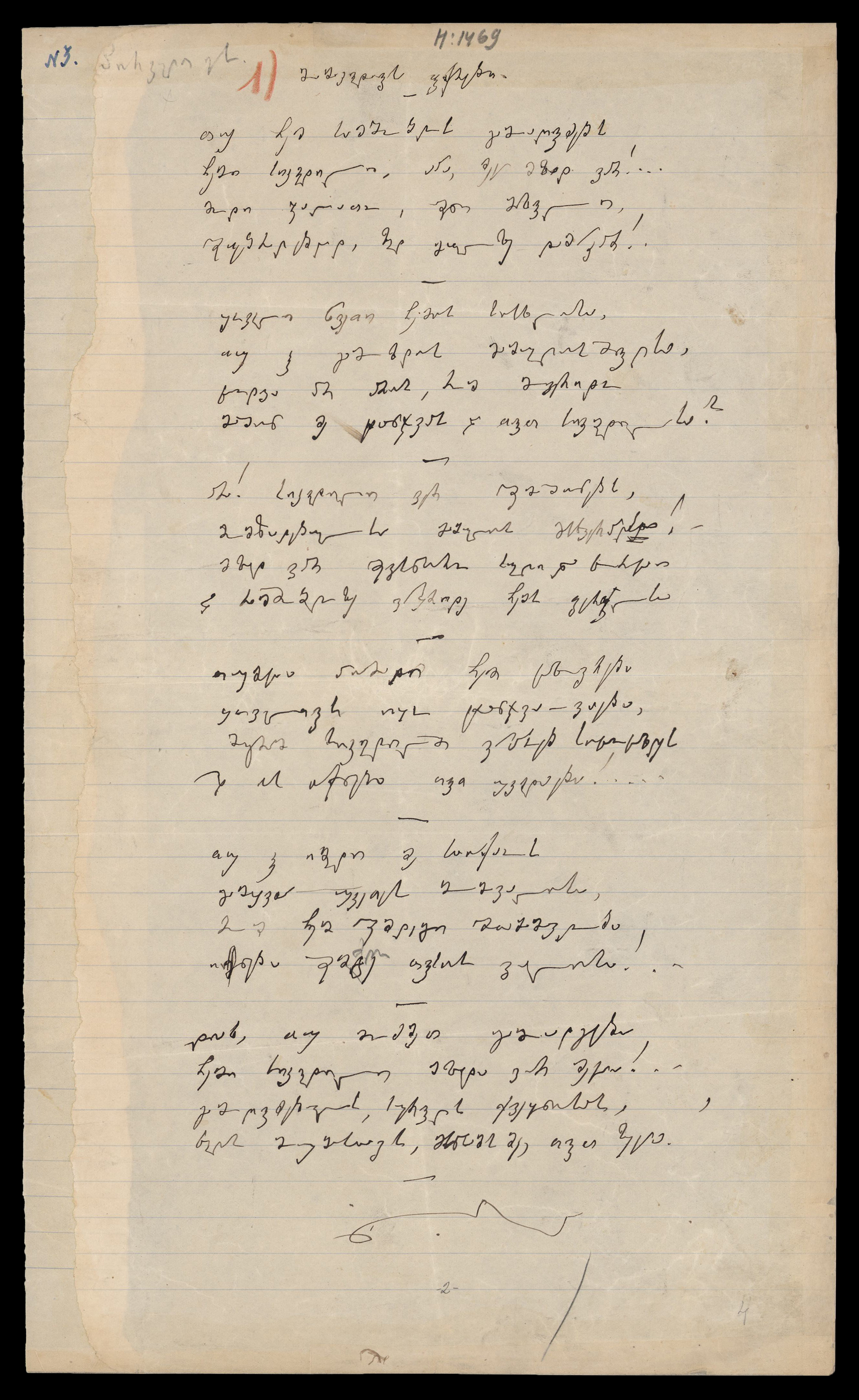

Akaki Tsereteli, "მომაკვდავის ფიქრები". National Centre of Manuscripts. Personal archive of Akaki Tsereteli

Akaki Tsereteli lived and created in the nineteenth century, a period that demanded titanic work and extraordinary effort to unify the Georgian people, develop a single language and a single system of thought, and to integrate Georgia into the system of developed countries. Akaki Tsereteli, like other great minds, was a leading figure in these transformative times. His work, spanning poetry, prose, dramaturgy, journalism, and witty and figurative expression, captured public imagination and exerted a lasting influence.

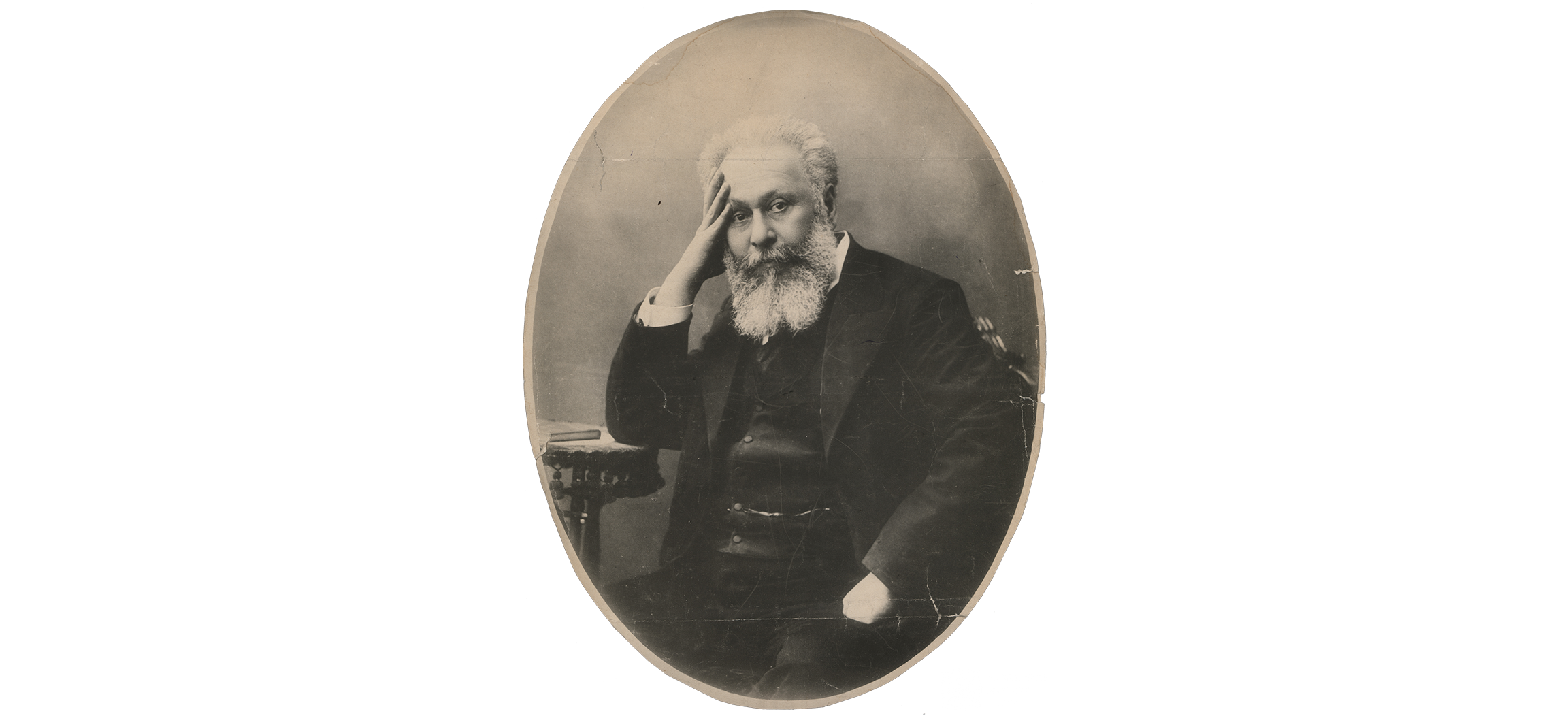

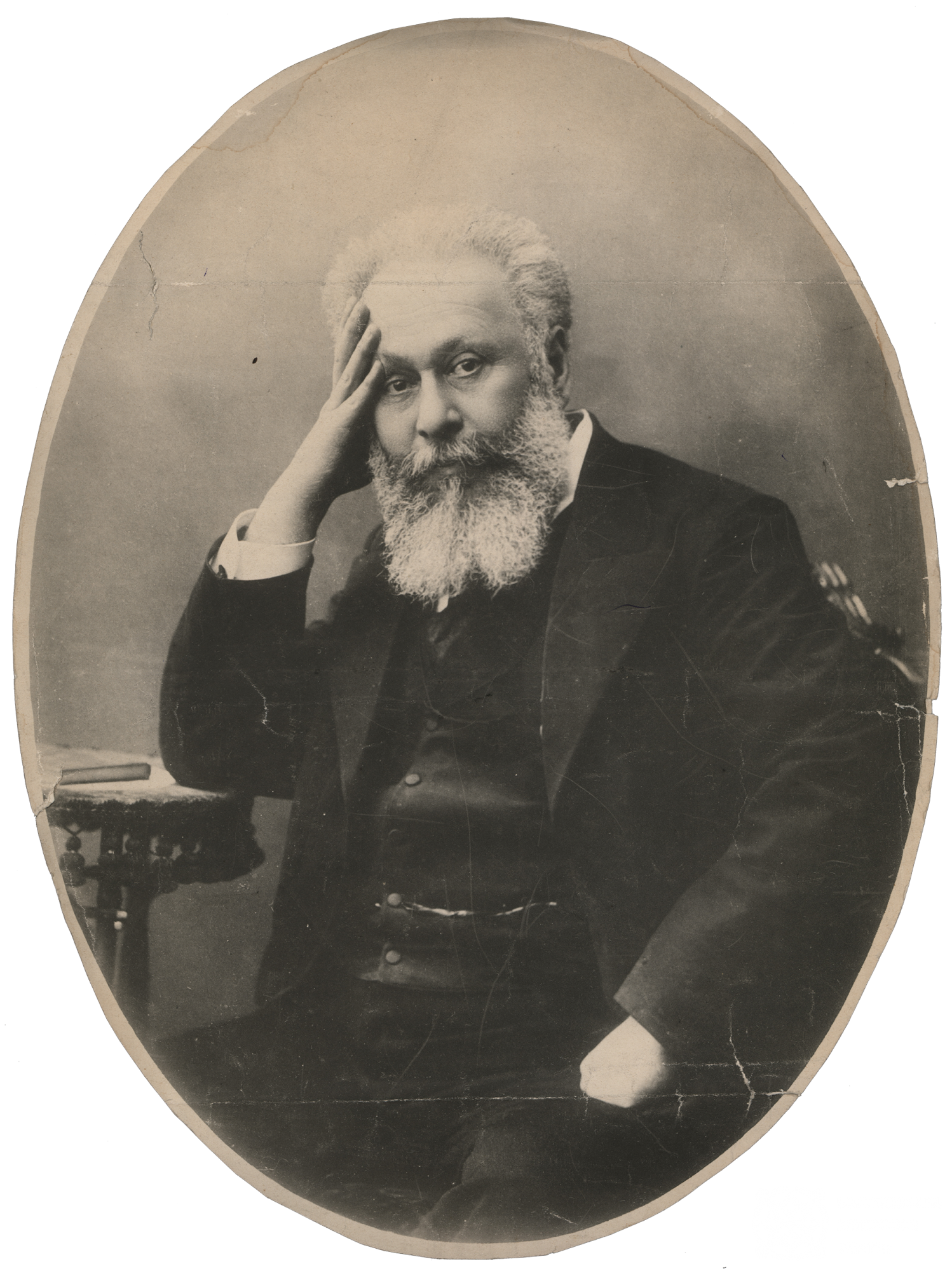

Portrait of Akaki Tsereteli. National Centre of Manuscripts. Personal archive of Akaki Tsereteli

There is an unusual folder in the poet's personal archive that neither belonged to him nor was sent to him, but which tells the story of Akaki Tsereteli like no other. Inside are fifty yellowed sheets: telegrams that were sent to the poet's personal doctor, Samson Topuria, from concerned citizens inquiring about the poet’s health.

Akaki Tsereteli's medical prescriptions. National Centre of Manuscripts. Personal archive of Akaki Tsereteli

Who was Akaki Tsereteli? Born into the family of an Imeretian prince, he was the heir to the Imereti king on his mother's side, and thus he was raised in the care of a nanny, as was customary in Georgian aristocratic families of the time. Children of noble birth often grew up in peasant households, sharing their lives, joys and difficulties, visions, tastes, and values. Under such circumstances, they developed an entirely different empathy for the people around them. Akaki Tsereteli, who, after graduating from Kutaisi Classical Gymnasium, wanted to build a military career, went on to enroll in the Faculty of Oriental Studies at St. Petersburg University. He returned to his country before completing his studies, and became involved in literary and public activities.

Akaki Tsereteli in student years. St. Petersburg, 1859

Any cultural figure—especially one of significant public stature—tends to reflect upon and consciously organize their intellectual legacy. In the case of Akaki Tsereteli, however, this process unfolded quite differently. After his death, no single, consolidated archive of his papers could be found. This absence is itself telling, reflecting one of his characteristic features: he never lived for glory.

Two years before his death, Tsereteli drew up a will, in which he transferred the copyright to his intellectual property (with a few minor exceptions) to the Georgian Historical and Ethnographic Society founded by Ekvtime Takaishvili. Following the poet’s funeral, the Society issued a personal appeal to individuals who had been close to Akaki. In this address, they stated that they were “collecting all items that had belonged to Akaki: his letters to acquaintances, relatives, and friends, as well as their letters to him; autograph manuscripts of the poet’s works; and any information that might be useful for the poet’s biography. We kindly ask you to provide your recollections of the deceased, and, should you possess any of his writings, private correspondence, or personal belongings, to share them with us.” The appeal was signed by Ekvtime Takaishvili. Thus began the process of preserving Akaki Tsereteli’s intellectual heritage.

Today, the materials in the archive of Akaki Tsereteli—comprising several hundred items preserved at the National Centre of Manuscripts—still bear clear traces of having been donated in this manner. It was through such contributions that numerous objects associated with Akaki Tsereteli were saved from loss.

Tsereteli is also remembered as the first public figure in Georgia to take an interest in the country’s deposits of coal and manganese, to engage European entrepreneurs in these ventures, and to take the initial practical steps toward their exploitation. In correspondence related to coal production, he once offered the following advice to Aristo Kutateladze: “Alertness, intelligence, energy, humbleness, working on the right and standing out on the left.” It would be difficult to argue that a man capable of such counsel lacked a deep understanding of life.

“I am waiting for the works of your playful pen,” Sergey Meskhi would write to Akaki Tsereteli without hesitation. The metaphor of a “playful pen” might, at first glance, evoke associations with lightness and lack of seriousness, yet, in reality, it emphasizes two main things: First, easy access to the poet, both from a communicative and perceptual, cognitive point of view; and second (and most importantly), the effortless, natural, and inherent fruitfulness of Akaki’s creative process. Sergey Meskhi’s letters reached the poet incessantly; “Droeba” was beset by constant difficulties. These appeals to Akaki Tsereteli assumed an almost standard form. Others addressed him in much the same way, often with requests resembling commissions, complete with specified themes. For example, Niko Nikoladze wrote asking him to compose a letter describing a common vice among officials, how eager they were to oppress their own people in the presence of others. Naturally, Ilia Chavchavadze also made a request—he wanted Akaki to collaborate with the newspaper “Iveria,” yet he feared that the poet might view this request as moral coercion and thus find it difficult to say either “yes” or “no.”

.jpg)

Ilia Chavchavadze's greeting card for Akaki Tsereteli. National Centre of Manuscripts. Personal archive of Akaki Tsereteli

It is intriguing to imagine what the 35-year-old Akaki, in 1875 at the peak of his career, might have felt upon receiving this letter from Niko Nikoladze: “I have seen a thousand and ten thousand proofs of the remarkable influence of your writing, and have come to value your talent and sensitivity even more, but… why is it, for example, that you cannot accomplish more than I, and that you do not have more influence on the country than we do? Only because, from the very beginning, you were held back by that dreadful difference between you and your friends. You always had untalented and restless friends, and, compared to them, you could achieve more without much effort or study. This made you lazy and discouraged you from diligent work.” There was a sense of deep sorrow in Nikoladze’s words. He profoundly understood the poet’s potential: even at this “peak,” Niko thought that Akaki was as yet unrealized. It is noteworthy that the publicist focused on “power” as something fundamental and essential, regarding it as more important than “melodiousness.”

Akaki Tsereteli possessed a distinctive poetic manner—he perceived himself as the “trumpet of circumstances,” a kind of conductor; a mediator between lived reality and the reader. The message conveyed through him was so charged with energy, so saturated with impulse, that it generated powerful social momentum, setting in motion forces that led to tangible and often positive change in society.

.jpg)

Akaki Tsereteli, "Poet". National Centre of Manuscripts. Personal archive of Akaki Tsereteli

In the 1940s, the great Georgian poet Galaktion Tabidze wrote a distinctive note in his notebook. At first glance, it may appear exaggerated; yet, upon closer reading, these very strokes, these contours, these impulses, may offer an answer to the question of who Akaki Tsereteli truly was for us: “Akaki Tsereteli: outwardly a lion (there are no people of such a look in Georgia today). In his gaze, there is a mockery that tormented many throughout the century. On his forehead is the mark of his ancestors: the steadfastness of the great Tsereteli family. Akaki should not have been only the king of poets, as he truly was in his own century, but rather a dynastic king: the ruler of Georgia. For Rubens, he would have been the perfect type—physically; for Nietzsche, he would have embodied the ideal of the Übermensch, both spiritually and outwardly. He should have been the chairman of the oldest senators, the best president of any republic, the prime minister of the strongest state. He should have been the one to pacify a nation in turmoil during a world revolution.”