Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

The Holy Cross Monastery in Jerusalem occupies a special place among the churches and monasteries that have been associated with the activities of Georgians in the Holy Land since the 5th c. It is also famous for the wall paintings that were executed in the different periods of its history, and especially for the portrait of Shota Rustaveli - the only preserved image of the famous 12th c. Georgian poet. Alongside their purely artistic value, the murals are also of particular importance in the history of the Georgian colony in the Holy Land.

Holy Cross Monastery in Jerusalem, general view.

The monastery was founded in the 5th c. by Vakhtang Gorgasali, the King of Georgia, and belonged to Georgians until the 18th c. In the 11th c., with the aid of Bagrat IV of Georgia, the church was rebuilt and decorated by the Georgian abbot Giorgi-Prokhore. In 1305 King David VIII of Kartli, East Georgia, regained the Holy Cross monastery from the Mamelukes, and his cousin, King Constantine I of Abkhazeti, West Georgia, commissioned a total renovation of the interior decoration.

Finally, in 1642 renovation of the murals was commissioned by Nikiphore Chilokashvili, abbot of the Holy Cross monastery and archimandrite of Golgotha - member of the famous Georgian feudal family who were supported by Prince Levan Dadiani, ruler of the principality of Samegrelo in western Georgia.

The monastery is surrounded by high, strongly-built circuit walls and resembles a fortress. It comprises a domed church with pillars, a belfry, various other buildings, and a vast yard. The interior of the church is typical for 11th -12th cc structures, while only part of the wall painting is preserved, comprising different painterly layers: from the 14th, 16th, and 17th centuries.

Holy Cross Monastery in Jerusalem, interior.

The murals underwent significant changes in the 20th century. Along with deterioration caused by time and climate, entire scenes and compositions that had still been in situ in the early 20th c. were intentionally destroyed; several fragments are now kept in museums in the USA. Certain images were covered with a layer of paint, as were most of the Georgian inscriptions accompanying the images. In the 1980s eight compositions and images were removed from the walls and sold at auction in Europe. Four of these were donated to the Georgian Orthodox Patriarchate by Georgian patrons.

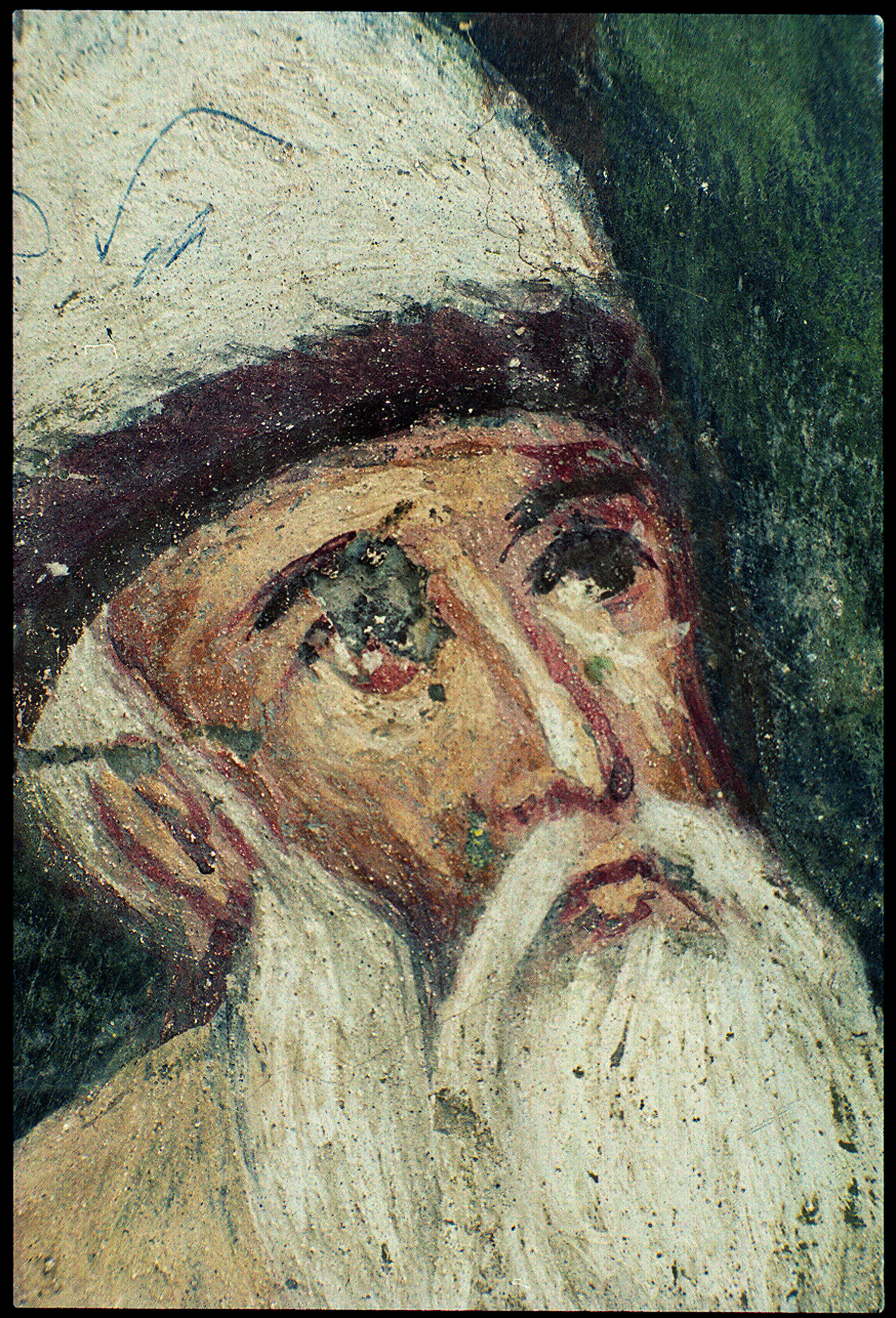

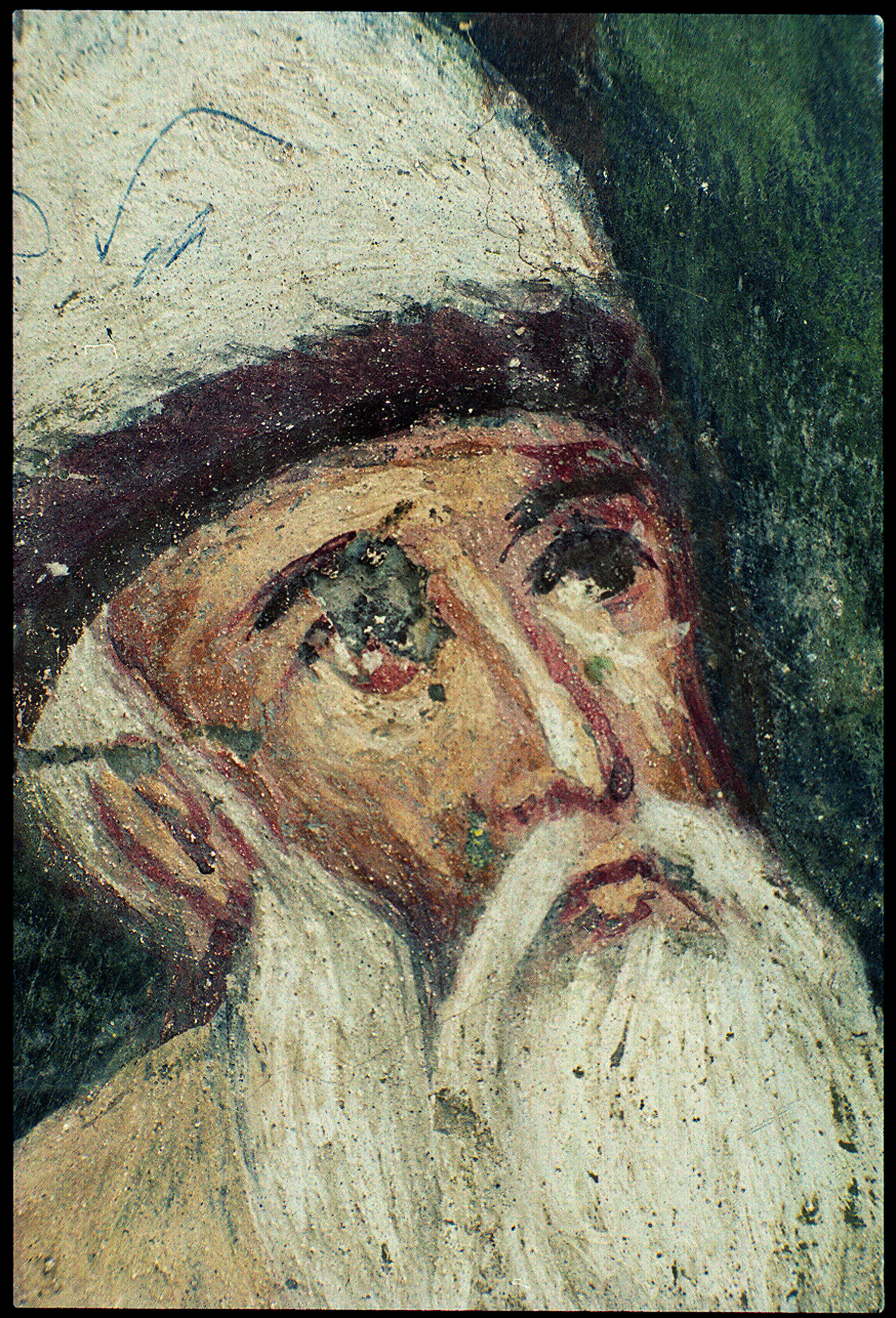

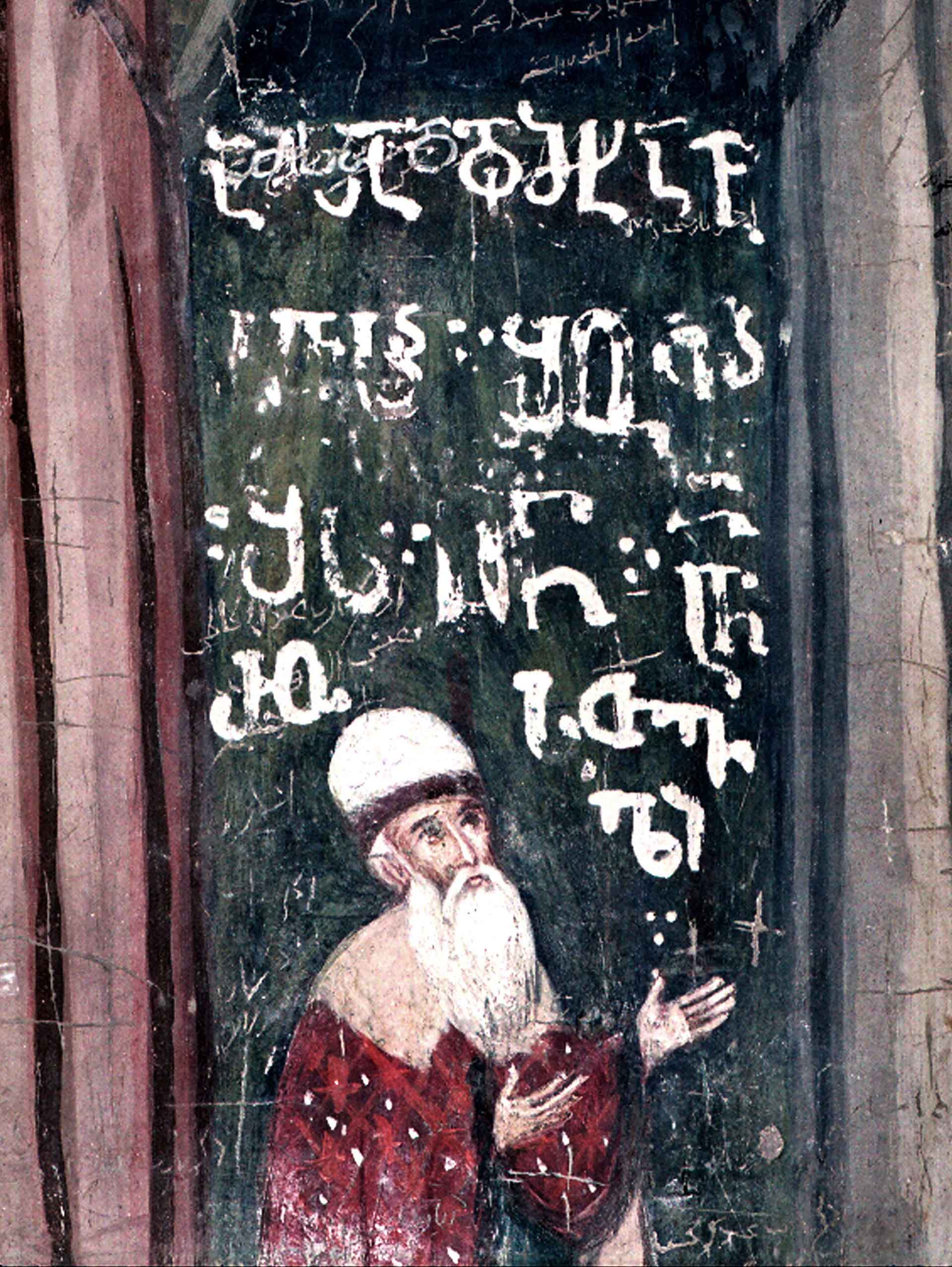

Many images that disappeared over the course of time, mostly those featuring Georgian historic persons, are known thanks to the descriptions and drawings of travellers and pilgrims from the 18th -20th cc. In June 2004, an unknown person destroyed the portrait of the world renowned 12th c. Georgian poet Shota Rustaveli, as well as part of the accompanying Georgian inscription. The portrait has been restored by a restoration team from the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Damaged image of Shota Rustaveli, June, 2004.

At present, paintings have survived in the sanctuary of the church, on the pillars in the naos, in the arch intrados, on the lower portion of the west wall, and around the west entrance. They date from the 14th, 16th, and 17th centuries. Unfortunately, the murals in the dome and on the vaults that might have comprised scenes of the Christological and most likely other cycles have totally vanished.

The program of the sanctuary murals is dedicated to the Virgin, including scenes from her life as well as a composition of the Glory of the Virgin in the conch (extremely fragmented); figures of the prophets and biblical scenes (Jacob’s Ladder, the Annunciation). All the images were executed in the 17th c. According to old descriptions, there were also scenes connected with the history of the Holy Cross (Abraham Giving Three Branches to Lot, Procuring the Cross by Queen Helen), which are now lost.

Anapeson, 14th c.

Some scenes from the Bible and the Gospels are preserved on the pillars (e.g the Visitation, the Council of Archangels, the Anapeson , Abraham’s Sacrifice, the Nativity of St. John the Baptist). Pair portraits of the prophets St. David and St. Solomon, St. Zacharias and St. John the Baptist, and other scenes and figures of saints represented in pairs dated to the 14th c. belong to the so-called Palaeologan style, together with the images of Christ Pantocrator and the Virgin on the pilasters of the sanctuary.

Peter the Iberian, 17th c

All the illustrations around the west entrance date from the 17th century, and display the stylistic character of Post-Byzantine painting. They comprise images of the Virgin and Child; St Peter the Iberian – the famous Georgian religious figure and founder of many Georgian monasteries in the Holy Land; the image of the True Monk – presumably Ioane the Laz, Peter the Iberian’s friend and “brother-in arms”; the Lord’s Hand with the Souls of the Righteous; St. Euthymius the Athonite and St. Giorgi the Athonite – famous 11th c. Georgian monks and literary figures who were active in the Iviron monastery on Mount Athos.

St. Euthymius the Athonite and St. Giorgi the Athonite, 17th c

According to 18th -19th cc descriptions, on the west wall there had formerly been an illustration featuring a row of Georgian donors who had contributed to the foundation and development of the Holy Cross monastery. Among them were the portraits of various kings of Georgia: St. King Mirian (4th c.), St. King Vakhtang Gorgasali (5th c.) and King Bagrat IV among many other historic Georgian persons whose representations no longer exist, such as the kneeling figure of Mariam, Queen of Georgia, on the chancel pilaster, from the 17th century.

Apostles St Peter and St Paul, 16th c.

The compositions featuring paired figures of saints are to be seen on the pillars, and date from the 16th c., i.e.: St. Peter and St. Paul, St. Basil and St. John Chrysostom, St. Maximus the Confessor and St. John the Damascene, with a votive representation of Shota Rustaveli at their feet.

St. Maximus the Confessor and St. John the Damascene, 16th c.

Shota Rustaveli, 16th-17th cc

Most of the paintings preserved until now are dated to the seventeenth century, (e.g. some rather rare scenes such as Daniel in the Lion’s Den, Wisdom Has Built Her House, Christ’s Temptation by the Devil, which are now only preserved in photographs. In addition, Elijah’s Ascension; St. Elijah and St. Elisha; St. Luke of Jerusalem (12th c. Georgian abbot of the Holy Cross monastery, martyred in Jerusalem in 1273), and St. Giorgi- Prochore (builder of the monastery in the eleventh century) have all now been donated to the Patriarchate of Georgia.

Ascension of Ilijah, 17th c.

The main idea of the wall painting’s theological program is the theme of the Virgin, i.e. the Incarnation and the Sacrifice on one hand, and the Earthly Church on the other. It seems that the iconographic composition of All Saints Sunday, which was very popular in the Orthodox World in the 16th –17th cc., also influenced this program.

Visitation, detail, 14th c.

Moreover, there is a strongly pronounced “national” air here,owing to the large number (more than 30!) of historic Georgian persons from different periods that are depicted on the walls of the church, resulting in a kind of “personified history” of the Holy Cross Monastery. It seems most probable that the 17th c. patrons and painters repeated the program of the 11th c. and the 14th c. paintings in detail.

Giorgi Arsenavri (Arsenishvili) with his son, 16th c.

Most of the images bear preserved Georgian and Greek inscriptions, including a large bilingual inscription above the west door that mentions Nikiphore Cholokashvili. The Holy Cross monastery and the murals preserved in its church represent the most significant monument to Georgians’ active presence in the Holy Land.