Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Georgian Modernism of the 1910s and 1920s is an exceptionally interesting and significant phase of Georgian culture, equivalent to the Western avant-garde of the 20th century. This period, which saw an extraordinarily active and "sober" cultural life, should first of all be explained by the political situation in Georgia at that time: the country's short-lived independence and its active contact with Europe. Unlike in Russia and the European countries, the fine arts in Georgia had to undergo the centuries-old development of realistic art at an incredibly accelerated pace. The dynamics of this development of artistic processes places Georgian culture in an entirely unique position at the beginning of the 20th century, when the creation of a new artistic form became the main concern of Georgian Modernism. Its goal was to establish a new, "modern" national form, which would be deeply Georgian and at the same time international, in order to fit organically into the global cultural context by bringing Eastern and Western cultural heritage together Georgia’s. Thus, it naturally came about that the new generation of artists on the one hand started researching Georgian art of the Middle Ages, and on the other hand strove to learn the fine art of Western avant-garde and to articulate European Modernism through artistic forms and symbolism. After Georgia’s declaration of independence on May 26th 1918, the political, social and cultural center of the country moved to the capital. Georgian poets, writers, actors and directors began to gather in Tbilisi. Georgian artists who had studied abroad gradually returned to their homeland. The charm of this creatively-charged Tiflis was reinforced by the healthy political situation, which made the city more attractive to all those who had tired of the spirit of the old world, and needed a cozy haven for the birth of a new one. Tbilisi also provided a particularly favorable environment for the Russian cultural elite. In this way, the Georgian and non-Georgian artists who were based in Georgia became the main protagonists of Georgian Modernism and the international cultural life of the 1910-1920s. Among them was Emma Lalaeva-Ediberidze (ემა ლალაევა-ედიბერიძე), a resident of Tbilisi and female artist of Armenian origin.

Lali in a dress of her own design. 1920s

The artist’s full name was Emma Lalaeva-Ediberidze, although she preferred to use the creative pseudonym Lali. Emma Lalaeva usually signed her works Lali/ლალი//Lallo/Лали. It seems as though she wanted to remain in history and be known among the global community by this pseudonym. Lali was born in Tbilisi in 1904 into the family of Arkady Lalayants (Lalaev), a photographer from Tbilisi and the owner of a photographic studio in what was formerly Yerevan Square (modern-day Freedom Square). She had been fascinated by art since childhood, and by 1921 was already enrolled at an art studio. Betweeen 1924 and 1928, she continued her studies in the Faculty of Graphics at the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts. In 1928, as a result of family matters, Lali left the art academy and decided to move to Moscow, where she enrolled in a decorative department. Nonetheless, she was unable to realize her dream, and ultimately stayed in Tbilisi and continued an active creative life there. In 1930, Emma Lalaeva married Giorgi Ediberidze – a professional engineer and geologist who had been educated in Germany. However, soon afterwards the couple’s life took a tragic turn: in 1938 Ediberidze fell victim to the Soviet repressions. Left a single mother of two young sons, Lali tried her hand at almost every genre of painting. She worked simultaneously as a painter, graphic artist, cartoonist, book designer, decorator, and stage and garment designer. She created bookplates and decorated Soviet feasts. Despite her active creative life, the artist was traumatized by the Soviet repressive system and rarely participated in exhibitions. Perhaps this was one of the reasons why Lali disappeared for a long time from the history of Georgian art.

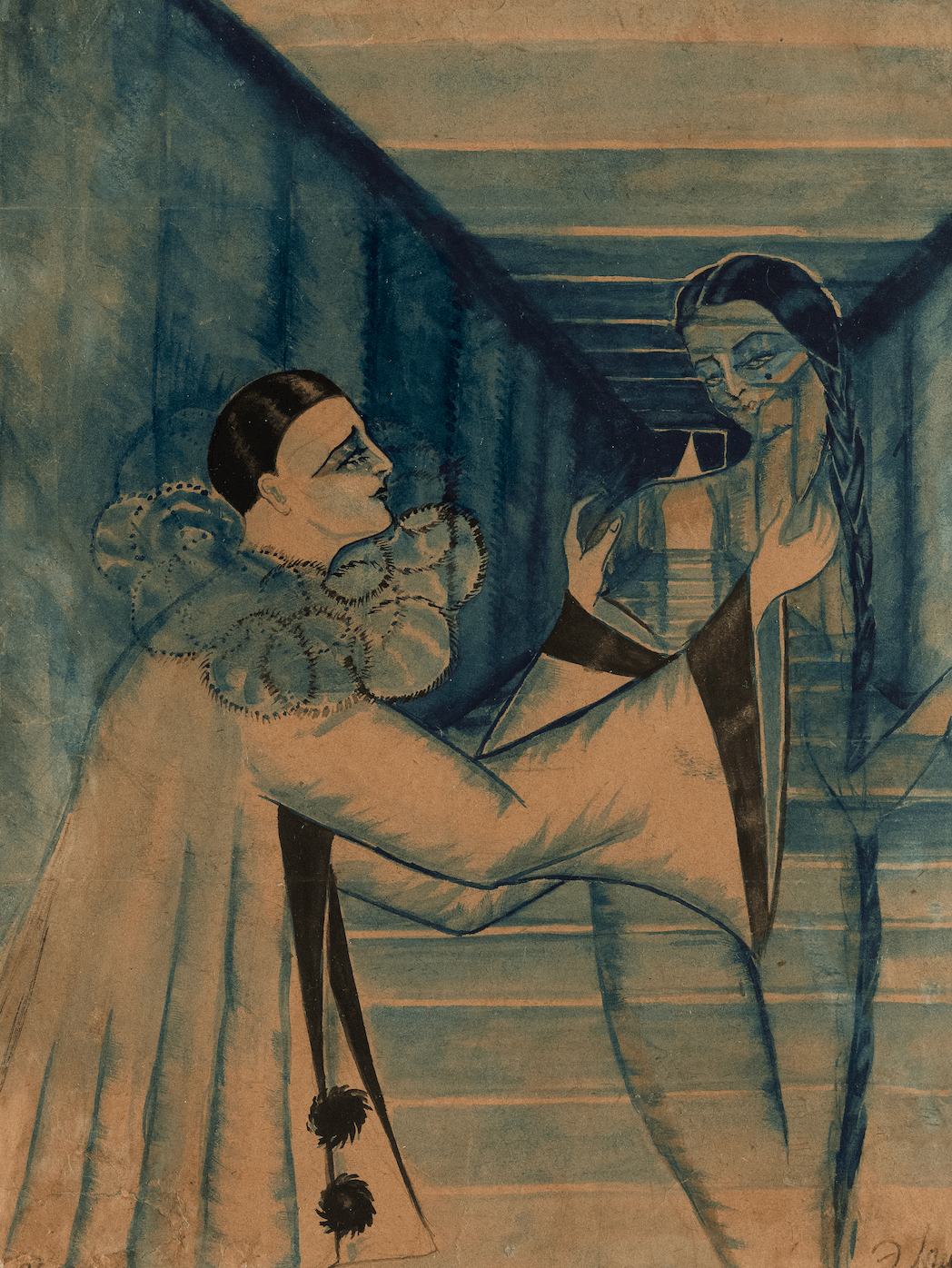

Ema Lalaeva. Ema Lalaeva. Piero. 21.5x15.5. Paper, watercolor. 1926. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

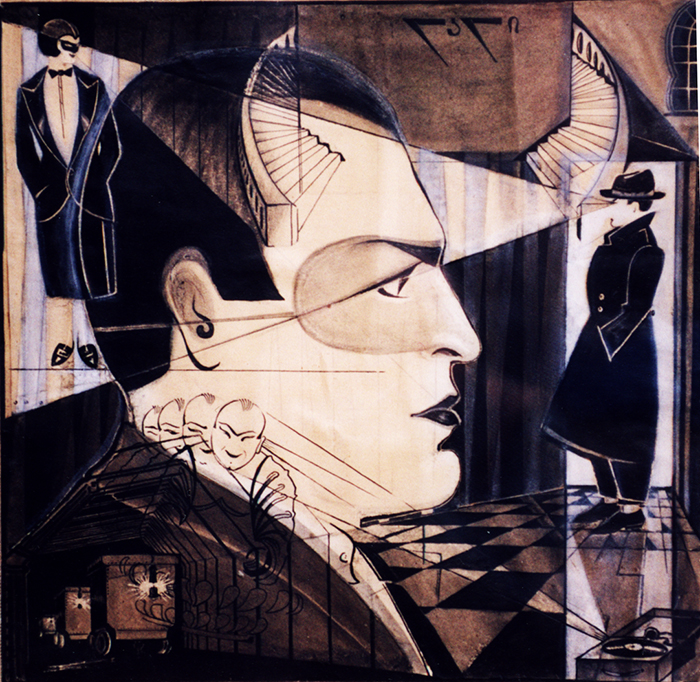

Ema Lalaeva. Portrait from Memory (Portrait of the Artist’s Husband). 37.5x38.5. Indian ink, watercolor, paper. 1920s

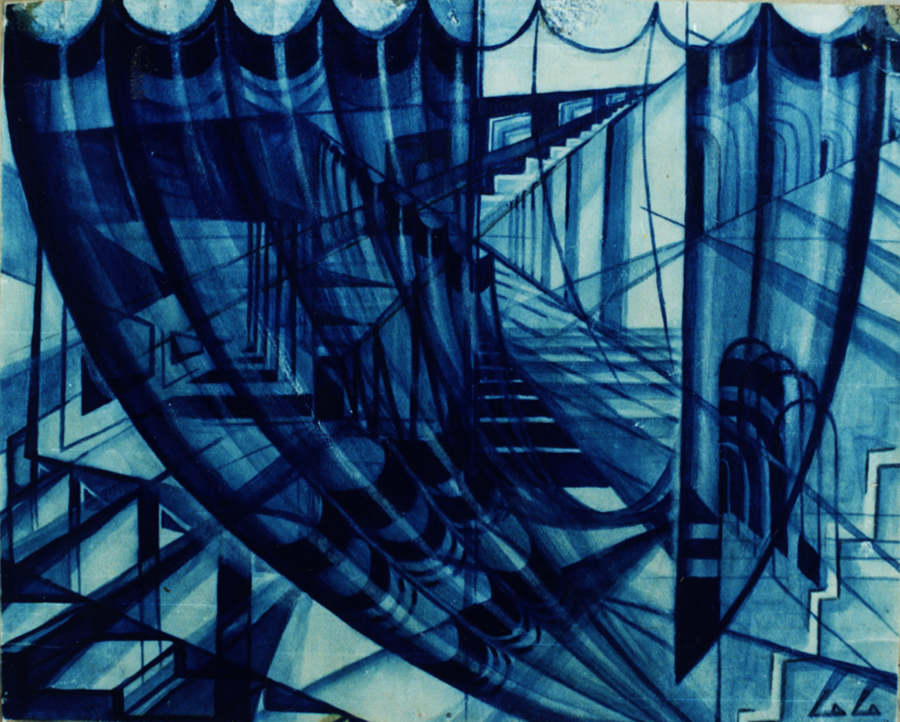

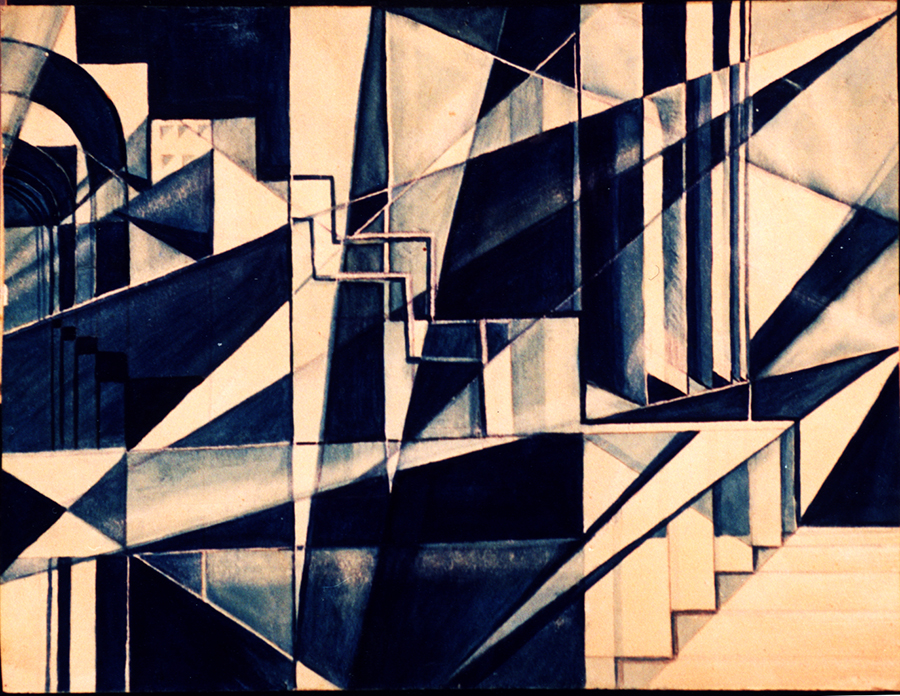

Nevertheless, it needs to be pointed out that Emma Lalaeva-Ediberidze is an exceptionally interesting representative of 1920s art. Lali was one of the most "leftist" painters among Georgian artists of that time. Her works clearly manifest an enhanced interest towards western avant-garde. As a bold artist from the early 20th century with an actively creative position, Lali tried her hand at almost all the avant-garde movements (Futurism, Cubo-futurism, Luchism (Rayonism), Constructivism, etc.), but she did not adhere to any of them in their pure form. The artist managed to create her own style without imitating anyone else. It should be noted from the very beginning that Lali was, first and foremost, a graphic artist who used a linear-graphic style as the leading motif in her paintings. Most of her works were executed on paper and more often on cardboard, where she utilized pencil, ink, sanguine, watercolor and gouache. In each specific case this determined her artistic image. Despite the similarities and differences, all her works have one common feature: the leading role of painting in a picture. The composition and color are subdued, making the line a dominant element.

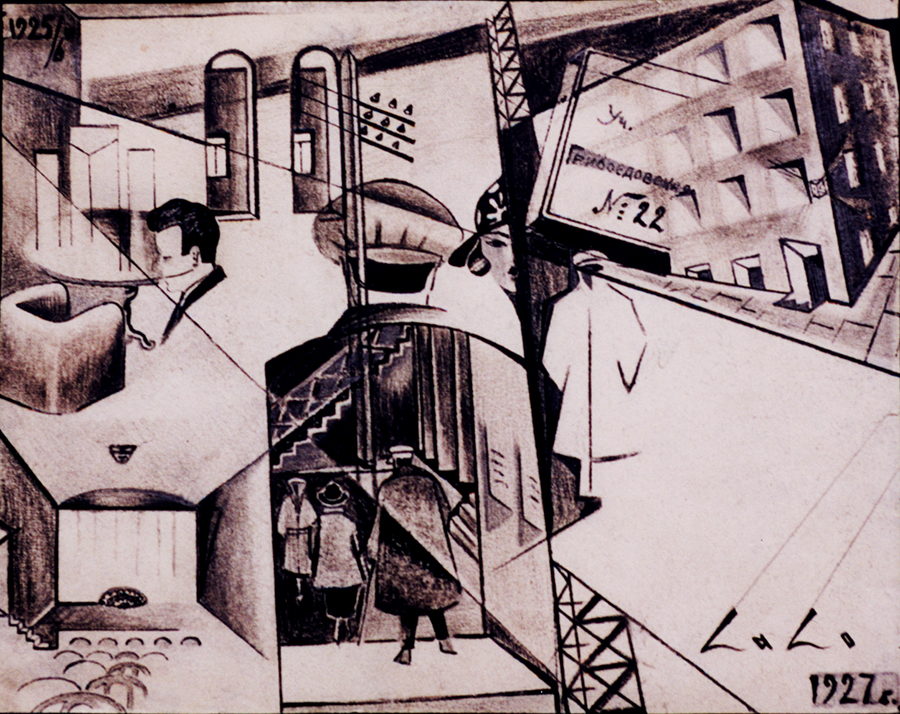

Ema Lalaeva. 22 Griboedov Street. 21x27. Sanguine, paper. 1925-1927

Ema Lalaeva (1904-1991) "Abstraction". Cardboard, mixed media. 28X23. ATINATI Private Collection

Ema Lalaeva. Cinematographic Motif. Pencil and watercolor, paper. 14.5x16.5. 1927

Ema Lalaeva. Lallo. Indian ink and pencil, paper. 68x59.5. 1926

Ema Lalaeva. Portrait of a Man in a Blue Jacket. Watercolor, paper. 28.5x22. 1920s

Ema Lalaeva. Self-portrait. Pencil, paper. 32.5x25. 1925

Ema Lalaeva. Industrial Composition. Oil, canvas. 62.5x54. 1925

Ema Lalaeva. Industrial Composition. Watercolor on cardboard. 25x29.5. 1926

Ema Lalaeva. Composition. Watercolor, cardboard. 25.5x29. 1920s