Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

The cultural life experienced in Tbilisi during the 1910-20s was one of the most important periods in Georgian art. Such a "sober" cultural life should be explained, in the first place, by the political situation in the country during that epoch – namely the country's short-lived independence and active contact with Europe. In 1918-1921, the political, social and cultural center moved from Kutaisi, an exceptionally intelligent city in Western Georgia, to the capital, Tbilisi. During that time, the capital of Georgia was transformed into a unique cultural oasis. Unlike the great imperial cities where the governments were constantly changing, Georgia was relatively stable, which contributed to the concentration of a creative educated class and flourishing in all fields of art. Georgian poets, writers, actors and directors organized meetings in Tbilisi. Georgian artists who had traveled abroad to study were also slowly returning to their homeland. In 1916, Dimitri Shevardnadze returned from Germany; in the same year, Kirill Zdanevich also arrived, demobilized after being wounded in the leg; in 1917, Ilia Zdanevich returned; in 1918, Shalva Kikodze and Davit Kakabadze returned to their homeland from Russia. The art group “Tsisperkancelebi” (The Blue Horns) moved from their home city of Kutaisi to Tbilisi as well. Luigi Magarotto pointed out: “The haughty and aloof young “Tsisperkancelebi” were unable to resist for long the charms of Tbilisi, which by that time had undoubtedly become an international city.”

The capital of a country that was by strange fate located between Europe and Asia, and built according to the principle of the “golden ratio,” was for many an exotic oriental-southern city; while for others it became an unexpected European city of the early last century. Remodeled and distorted a thousand times, one may say its degenerate urban pattern even today preserves the diverse cultural, artistic-architectural and ethnic narrative of Tbilisi from that epoch. After all, at that time it was totally alive with all its diversity and variety, offering its own multicultural features to everyone who wished to visit the capital of this newly independent country. At that time, Tbilisi still preserved intact the complex and chaotic medieval system of winding streets in Kaloubani; you could also elsewhere observe the neatly organized street system presented in a European manner, Art Nouveau style buildings decorated with refined sculptured façades and geometrically arranged neoclassical structures. In the city, one would come across Armenian-Gregorian and Catholic churches strewn amongst the domes of Georgian Orthodox temples; a Neo-Byzantine style Military Temple – Soboro, and even a Protestant ‘kirche’; the Atashgah “fire temple” – a cult building of fire worshipers, which at that time was already an historic legacy; you would also find a synagogue and a mosque erected near each other. The multitude of public and residential buildings fitted in freely with dwellings that were decorated with curved wooden balconies; European style castle hotels, as well as Cadets military buildings and caravanserais; samikitno (taverns) and European style cafés. The ethnic population of the city included Armenians, Jews, Russians, Greeks, Tatars, Germans, and many others. The charm of Tbilisi, "mixed" with such strange, often contradictory and unexpected socio-cultural or urban elements, was accompanied by a stable political situation, which made Tbilisi more attractive to those longing for a safe haven, exhausted of watching the old world dying and witnessing the birth of a new world pathos. Tbilisi offered a particularly favorable environment for the Russian cultural elite. According to L. Magarotto: "after the end of the First World War and the overthrow of Tsarism, for the Russians, whose homeland had been destroyed by civil war, with all that misery, hunger and death, in the words of Osip Mandelstam, “[Tbilisi] was perceived as a new Switzerland; a neutral and sinless tiny piece of land.” However, the political safety of Tbilisi, its ephemeral, creative freedom and phantasmagoric artistry turned out to be short-lived. Rejis Geiro presents a very precise description, "The feeling of freedom , which during the first twenty years of the 20th century traversed the whole of Europe from West to East, nowhere else managed to reach such perfection as it did at the end of its long journey in Tbilisi, when it there collided with Asia. The sorrowful fact is that Georgia is a small country located between empires; as such, its freedom at that time was swept away by the wind in such a way that the West could not even manage to catch a glimpse of it”.

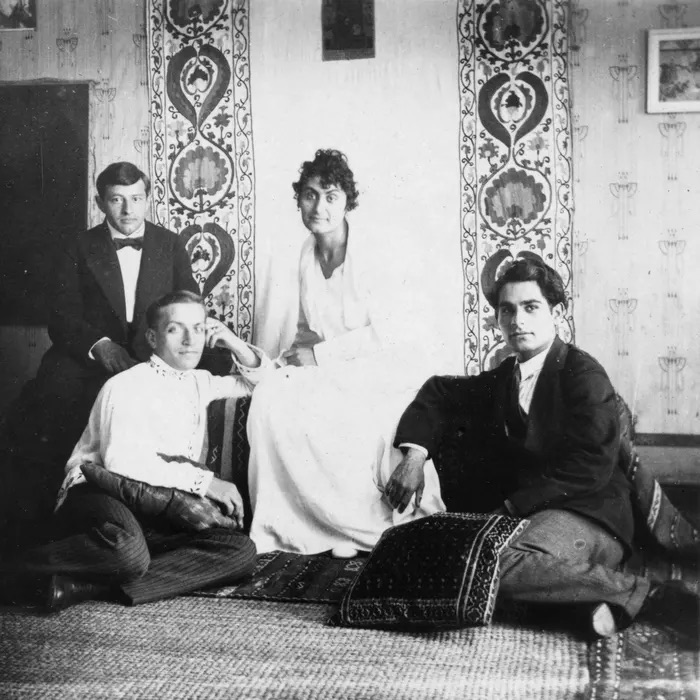

From left: Dimitri Shevardnadze, Mikheil Chiaureli, Ketevan Maghalashvili, Lado Gudiashvili. Paris, 1920-1921

From Left: David Kakabadze, Elene Akhvlediani

In the middle: Lado Gudiashvili, David Kakabadze

Nevertheless, until then Tbilisi attracted Russian writers, poets, artists, musicians and actors, like honey attracts a bee... together with Georgian host artists, they became the major figures of Tbilisi's cultural life. In 1919, Grigol Robakidze wrote: “Tiflis (Tbilisi) lives through an aesthetic perception of the universe. It used to be like this and it still is. One could mention many names… They are united under the umbrella of art. People of different origins, different cultures, brothers in art… We believe in this new internationalism. Its foundation should be laid here in Tiflis.”

Kirill Zdanevich and others in Tbilisi

Gigo Gabashvili with his students in painting auditorium of Tbilisi State Academy of Art

The art history of the 1910s and 1920s is an exceptionally interesting and significant phase in Georgian culture. During that time, Tbilisi bohemian life reached its culmination, as if it were capped in a heady smoke, the creative life was constantly seething. Even a brief list of the cultural events of that period is enough to prove this.

Upon his return to Georgia from Germany in 1916, Dimitri Shevardnadze founded and led the “Association of Georgian Artists”, which actively began the study of Georgian fine art, and largely contributed to the creation of museum works, supporting young Georgian artists and stimulating exhibition activities. One could see a particular revival in the field of theater; starting from 1917, many different theaters and studios were opened in Tbilisi. In September of the same year, the Mini Theater began its performances; in 1918 the “Institute of Performing Arts” was established. At the end of the 1910s, along with the theaters intended for general audiences, a wave of artistic cafés began to emerge in Tbilisi, which very well depicted the existing artistic atmosphere at that time, and most importantly created a new space for the city’s creative activities. One of the more important events of the cultural life of Tbilisi in 1917 was the opening of the artistic café "Fantastic Tavern," with the initiative and support of Yuri Degen, where poets gathered to recite poems, interesting meetings were held, and lectures were given. The walls of the dining room were painted with phantasmagorical compositions – the interior was decorated by Lado Gudiashvili, Alexander Petrakovski, Niko Nikoladze, Yuri Degen, Illia Zdanevich,Kirill Zdanevich, and Lado SerGey in 1917. Several organizations founded at that time also included “Futurvseuchbishche” (a term that Vladimir Khlebnikov invented, which in Russian means “Future University”.), led by Alexei Kruchenykh, Igor Terentiev, and Ilia Zdanevich, which was devoted to educational and artistic productions. In 1917, the “Brotherly Consolation” cafe-club was opened; In 1918, an intimate cabaret “The Peacock's Tail” was created for a narrow circle of art lovers (the interior walls were painted by Kirill Zdanevich and Sigizmund Valishevsky), where, in addition to extraordinary theatrical performances, concerts and meetings, so-called disputes were also held. In the same year, the theater-studio “Argonaut’s Boat” (painted by Kirill Zdanevich, Lado Gudiashvili, and Alexander Bajbeuk-Melikov) began its performances. In 1919, with the initiative and support of the “Tsisperkancelebi” (The Blue Horns) (Paolo Iashvili, Titsian Tabidze, Valerian Gafrindashvili, Ioseb Grishashvili, Nikolo Mitsishvili,and Grigol Robakidze), the “Kimerioni” café was opened, which was originally intended to be a “café-club of Georgian writers.” ”Kimerioni” in fact became a gathering place for Georgian poets, and not only for them.

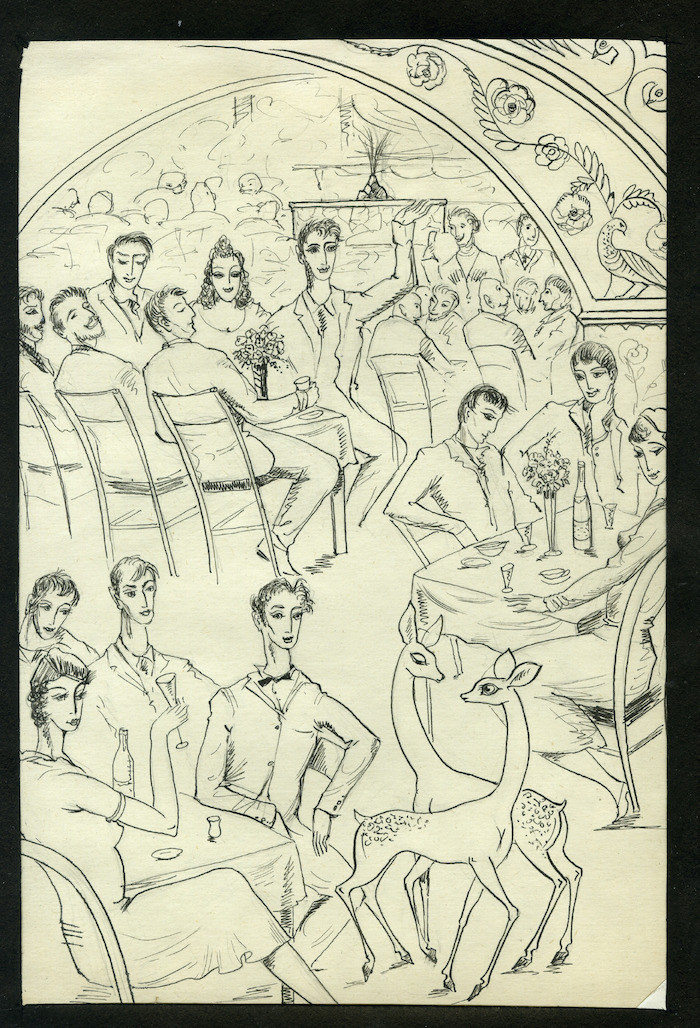

Cafe "Kimerioni"

Georgian and Russian poets, artists, musicians, and actors would also assemble there. Sergey Sudeikin, one of the founders and artistic-decorators of “The Stray Dog Café” and the creator of the Cabaret “Halt of Comedians”, was especially invited to decorate the café; he arrived in Tbilisi together with his wife in 1917. Davit Kakabadze and Lado Gudiashvili also participated with Serge Sudeikin in painting the interior. In the same year, the artists Lado Gudiashvili, Sergey Sudeikin, Joseph Charlemagne, Eugene Lanceray, E. Kocherian and others joined the group “Small Circle,” where they actively organized exhibitions. Nonetheless, the exhibition life of avant-garde Tbilisi has its chronicle. As early as 1916, Kirill and Ilia Zdanevich, together with Mikhail Le Dantu, organized an exhibition of Niko Pirosmanashvili's (Pirosmani’s) works at the Zdanevich house. One of the main events was the large retrospective exhibition of the works of K. Zdanevich, in particular the works of the left movement, which was held in 1917 (128 pictures, introduced in the catalog by A. Kruchyonykh and I. Zdanevich); this was followed in 1918 by Lado Gudiashvili's exhibition. In 1918, the “Exhibition of Moscow Futurist Pictures” was organized, where works by Kazimir Malevich, Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, Vladimir Tatlin, Pavel Filonov, Alexander Shevchenko, Ivan Kliun, David Burliuk and Olga Rozanova were presented. We should by all means also mention the landmark exhibitions of Georgian artists that were organized in 1919 at the Temple of Glory under the leadership of Dimitri Shevardnadze.

Lado Gudiashvili. Cafe Kimerioni. Paper, Ink

David Kakabadze. Cubist Composition. Canvas, oil. 1920

Publishing activities were also undergoing an upswing. Poetry collections, literary-artistic magazines and newspapers (including many in Russian) were actively being published. Such periodicals were: the journals "ARS " ("Arsi", issued by the "Guild of Poets" united Tbilisi Acmeists led by Sergey Gorodetsky; unfortunately only four copies were published); "Phoenix" (a Russian-language journal, published by Yuri Degen, who also founded the publishing house of the same name ); "Kuranti" (a Russian-language journal edited by Boris Korneev); "Orion" (editor/ writer Sergey Rafalovich,); “Safironi“ (published in 1916, editor: Giorgi Leonidze); "Nemsi", "H2SO4"; "Meotsnebe Nyamorebi" (editor Valerian Gafrindashvili); “Shvildosani” (The Archer) (published in 1920, edited by Sandro Tsirekidze); "Theatre and Life" (editor: Josef Imedashvili); Almanacs: "Fantastic Tavern" (1918) and “Sofia Melnikova's Fantastic Tavern” (1919); Newspapers: "Khelovneba"(Art) (published in Russian in 1919, supervised by Boris Korneev and Vasily Katanyan); "Arlekini"( Harlequin), "410" (only one copy was published on July 14, 1919); "Akhali Dghe" (New Day), "Saqartvelo"(Georgia), "Barikadi”(Barricade) (editor: Titsian Tabidze); "Bakhtrioni" (editor: Giorgi Leonidze) and others. Russian Futurists played a large role in developing this sphere. Their work was particularly distinguished by specific activities. In 1919 the “Company 410” published over 50 books.

In 1917, a series of public speeches by the Futurists began, which often ended in scandals and loud incidents. In November 1917, Aleksei Kruchyonykh was recognized as the father of the "Vsiochestvo" (Everythingness) movement and of Zaum – a poetry style utilizing nonsense words, thus establishing the “Futurist Syndicate,” which was immediately acknowledged by I. Zdanevich, K. Zdanevich, N. Chernyshevsky, L. Gudiashvili, and Z. Valishevsky. In the first such major event (November 20, 1917)organized under the leadership of A. Kruchonikh and I.Degen, the most significant active participants were L. Gudiashvili and other Georgian poets and artists. In 1918, together with K. Zdanevich, L. Gudiashvili organized the second event of the "Futurist Syndicate" (the "Futurist Syndicate" ceased to exist in the spring of 1918); in 1922, the Association of Georgian Futurists was founded. On 25th February 1921, after the defeat of the free Georgian troops by the Red Army on the outskirts of Tbilisi, Russian troops entered the capital, and soon Georgia became a part of the newly established USSR. At that time the prosperity of Georgian cultural life was gradually declining, the country was anticipating changes; in 1922 a small revival was observed, when at a literary evening organized on April 22nd at the Tbilisi Conservatory, the Georgian Futurist poets announced their existence to the public: that was when a new movement of the Futurist wave began to rise. In 1924, they published the magazine "H2SO4" (Illustrated by I. Gamrekeli); in 1924-1925, the journal "Literatura da Skhva" (Literature and others) (editor: N. Chachava, artistic rendering by K. Zdanevich); in 1925-1926 the journal "Drouli" (Timely) was published. In 1928 publication of the last journal of the Futurists "Memarcxene" (Leftist) ceased to exist.

Boris Pasternak in Georgia

From left, sitting: Vasil Barnov, Giorgi Leonidze, Iakob Nikoladze. Standing: Kirill Zdanevich, Valerian Gaprindashvili, Paolo Iashvili, Titsian Tabidze. 1924

Valerian Gaprindashvili, Titsian Tabidze. 1916

This creative environment loaded with important cultural events prompted Grigol Robakidze to call Tbilisi a "Fantastic City." In one of his novels, "Falestra" he stated: "Tbilisi has always been a strange city, but in 1919–1920 it became even stranger… "During the period of state independence, this small “fantastic” capital opened its artistic boundaries wider. With its versatility, simultaneity and vivid freedom, Tbilisi motivated avant-garde artists towards limitless creative activity. A bohemian way of life was equated with active creative work and freedom of thought, and so Georgian poets and writers often appeared as its apologists. The artistic community of Tbilisi moved from their homes and workshops to the streets and cafés. The capital of Georgia became a “New Paris,” its noisy, crowded "avenues" and squares attracted Georgian artists more than the many-colored "Meidan". According to Georgian artists, beyond that noisy, enchanting, Paris-like Tbilisi bohemian entourage, one would feel a creative, business-like atmosphere. Nonetheless, this everyday life filled with cultural events; the extravagant, young people and talented artists following European fashions and trends with self-righteous artistry; the mild modernist wind that turned into a storm and invaded Georgia as a result of the temporary opening of the country’s borders were only superficial effects. The true essence should, perhaps be seen beyond them – in particular, in the process of internal, no less active creative exploration of outwardly efficient everyday life, which gives us the right to say: the cultural and artistic life of Tbilisi during the 1910s and 1920s was arguably the single most significant phenomenon in the history of modern Georgian art, not only resulting from its unique location at the crossroads of North and South, East and West and being introduced to contemporary European art beyond the borders, but also due to the fact that during that epoch, strength was being regained in the bosom of Georgia. It was an era when everything had its own rational, theoretical basis. This was one of the most "cognitive" times in the history of Georgian culture. It was the beginning of discussions, arguments, and analysis aimed at escaping the crisis; when national self-awareness began to take shape, and all the above mentioned occurred through the reconciliation of Eastern-Western and Georgian cultural achievements. An attempt was made to create a new, "modern" national form, which would be deeply Georgian: only genuine, pure Georgian, but organized in such a new way that it could be naturally included in the world discourse. The field of art became an arena for such exploration. As Geronti Kikodze stated: “The richness and strength of a national spirit or its poverty and inadequacy is nowhere more clearly and tangibly depicted than through its language. Language reveals both the flexibility of thoughts and variety of feelings, as well as the animality of the national temperament. This is because language is not a dead dictionary of words and expressions; it is a living treasury of ideas and emotions.” And truly, at that stage of the development of Georgian history, the return of national self-awareness and the longing for a rich soul were almost the same. Nationality, namely restoration of the internal, organic integrity of a Georgian man to his own roots, is of equal value to returning to the father's bosom, much like spiritual salvation. Georgians considered art as one of the principal weapons for the spiritual salvation of the nation. As Geronti Kikodze wrote in 1917: "Political fight alone is not enough to revive our homeland; the national spirit should also revive with the help of art.”