Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

In Leila Shelia's artwork, one can discern distinct elements of separation, irreversibility, and irrationality. These elements emanate primarily from the powerful feminine characteristics that stand in contrast to more traditional masculine traits that are often to be found in Georgian art. This contrast is not aggressive, but rather transgressive in nature. The central theme revolves around an unending diary that is crafted with feminine sensibility and intuitive impulses. In the diary, the pages are in the form of painterly canvases, which serve as a unique testament for breaking free from the rigid constraints of the largely male-dominated Georgian art scene. These pages embody a personal narrative, which is primarily driven by a strong determination to embrace the will of painting, life, and one's inner voice. Leila's artwork lacks solidity. She does not employ direct words to persuade viewers; she merely enables them to locate weak areas or gaps in the abundant pictorial-cultural conventions – and of course one should notice that this is not on the surface of the paintings, but rather in their cracks.

Leila Shelia. Untitled. 128x95,5. Oil, canvas. 2018. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

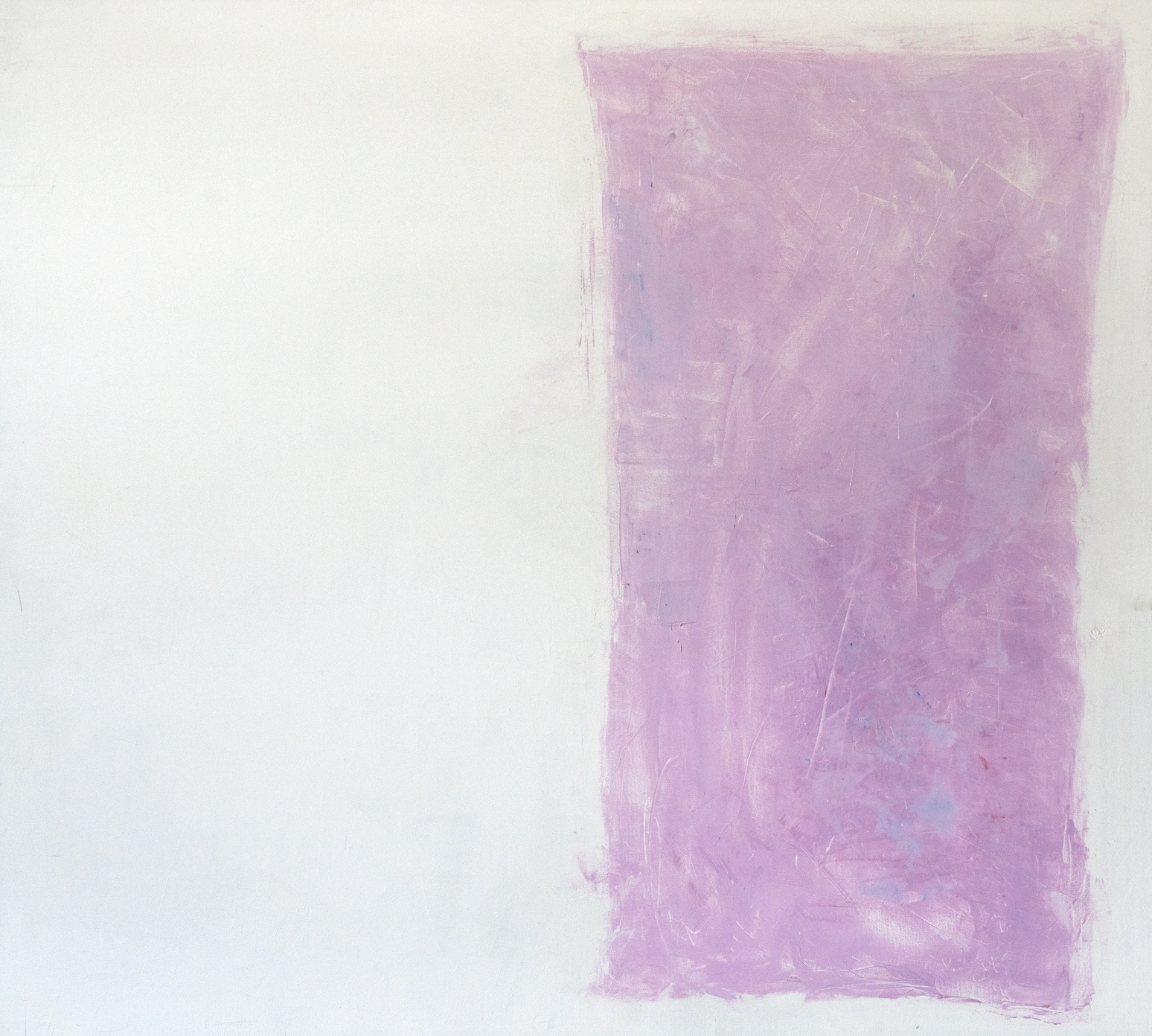

Leila Shelia. Untitled. 105x141. Oil, canvas. 2022. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

During the 1980s and 1990s, within the Georgian artistic space, painting successfully liberated itself from the prevailing realist traditions that were typical of the era of social realism and regime-thawing. Georgia had also fallen victim to the isolationist policies of the Soviet Union, which is more commonly referred to as the 'Iron Curtain.' Consequently, artists in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s began developing abstract painting at a delayed pace, which was due either to their limited access to Western influences, or a result of the process of intuitive exploration. While Informalism and Tachisme flourished from the 1940s to the 1960s in Europe, alongside Abstract Expressionism in the United States, Georgia experienced a considerably delayed emergence of these movements, with a distinct context taking root approximately two decades later. Shura Bandzeladze, Edmond Kalandadze, Jibson Khundadze, and Guram Kutateladze played pivotal roles in the intensive development of Georgian abstract painting until the 1970s. Subsequently, in the 1980s and 90s, abstract painting was taken up again by male artists – namely Gia Edzgveradze, Irakli Parjiani, and Levan Lagidze. While this list is not exhaustive, the predominant presence of male artists from the 1960s through to the 1980s clearly underscores the supremacy of a masculine monolith within the Georgian art scene during that period. Similar to Georgia, in the Western artistic space of the 1940s and 1960s, abstract painting was chiefly the concern of male artists. In the Georgian art scene of the 1990s, painting returned to figurative styles and adopted more multimedia and pluralistic approaches. Nevertheless, despite these changes visual representation remained largely homogeneous, and the emerging generation of artists appeared to form a closed, again predominantly male circle. Leila Shelia's existence, development, and movement within the dynamic realm of Georgian art testify to her individualism and self-cultivation as an artist.

Leila Shelia “Helios”. 96x170, Oil, canvas. 2023. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Although Leila Shelia is a distinct, independent, and unique artist, certain questions still arise regarding her artistic choices. Why did she opt for abstraction as a consistent mode of self-expression? Where did her inspiration spring from? Who influenced her? What led to her departure from realist art, and what drove her towards generalization in the 1990s? During a particularly difficult political period the nation was undergoing, the artist stated in an interview that she had displayed an abstract painting style since her childhood, she was influenced by her early years that had been spent in Abkhazia, and that nature itself was an infinite, generalized form. She developed an abstract way of thinking through watching the forest, the sea, flora, and celestial bodies – all of which later found new forms of expression and materiality in her painting. Equally significant is the fact that in post-Soviet Georgian painting of the 1980s and 90s, many artists consciously steered clear of realistic styles. Some delved into explorations of historical themes, while others investigated religious and mythological motifs. In stark contrast, Leila Shelia rejected the path of realistic or figurative painting in favor of abstraction. This form of self-determination and the given generation’s avoidance of reality can undoubtedly be attributed to the challenging socio-political backdrop of the era, which was marked by civil unrest and devastating wars... In America and Europe, abstract expressionism served as an avenue for disillusioned artists who were seeking an escape from the monotonous grind of reality. Abstract expressionism represented a visual thesis and response to the political shifts that had been brought about by the First and Second World Wars, Nazism, Communism, and the fragility of Western pseudo-values. Similarly, in the context of Georgia, abstract expressionism and Leila Shelia's interest in this tendency both share a historical-cultural regularity.

Leila Shelia „In Space”. 80x100. Oil, canvas. 2005

Leila Shelia „White Noise“. 90x100. Oil, canvas. 2019

Leila's artwork, which for some reason, I perceive as being akin to a diary. It is divided into specific stages, or chapters. The first chapter encompasses pieces of work which are based on deconstructing figurative or partially realistic forms of figures, and the enhancement of color and spots. I am particularly fond of the second chapter. During this phase, the artist overlays multiple layers, disperses various geometric-organic shapes as colored spots without any apparent connection, and leaves the initial layer as a central circular spot in the center of the composition. The round spots are a kind of irrational window or opening. They open a window onto a kind of mysterious space, much like the paintings of the Renaissance period. During this era, religious and mythological scenes were anachronistically — one might even say "postmodernistically" — blended with European life of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, where humans and cultural "Titans" appeared alongside one another in a single timeframe. Leila's circles and spots are the boundary between the irrational and the rational. They are even reminiscent of Dadaist collages, where mirrors affixed to the surface reflect the viewer – suggesting that the artworks might lack meaning without this interactivity, this reflection of the human presence. The third chapter unites minimalist monochromatic pieces with discordant multicolored surfaces that seem to defy gravity. In the fourth chapter, we encounter seemingly incoherent or atonal musical compositions. Scratches, hieroglyphs, paintings within rectangular frames, and the scattering and juxtaposition of vibrant colored spots all come together to form a unified harmony: one that is conditioned by feminine sensibility. The listed sub-chapters are afforded their own harmony under the title "Unbearable Lightness".

Leila Shelia. Untitled. 105,5x141. Oil, canvas. 2023

Leila Shelia. Untitled. 70x90. Oil, canvas. 2018

Leila Shelia. Untitled, 62x85. Oil, canvas. 2016

Leila Shelia's artwork deviates from the traditions and ideals upon which abstract expressionism was founded. In this context, the dynamic visual elements do not disrupt the essence of the artwork or painting; rather, they seem to spill over transgressively and transform into tangible art objects, seamlessly integrating with the surrounding space while also endeavoring to reinterpret modernist concepts. The unification of several ideologies, aesthetics, or beliefs is undoubtedly present at the beginning of postmodernist-collage thinking or contemporary (conceptual?) art. Leila Shelia's self-mythologizing, continuous narrative is essentially based on a pictorial and conceptual generalization of existence, as well as the search for the self and "lost time" in the abstract zone.