Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

In the 1910-1920s, editing principles were introduced into almost all fields of art: painting, literature, theater… However, since editing is primarily associated with movies, these specific tools primarily used in film (screens, projectors) immediately enriched the works of innovative scenographers. The concept of editing was well-suited to the consciousness of a “new” audience who were loaded with diverse information and longed for a frequent change in the means and forms of artistic impact, visual and sound impressions. Mirroring the rapidly changing state of society that was occurring under the influence of technological advancement, the theater began actively implementing technological innovations. New methods were introduced that completely changed the relationship between space and time. For this new type of art, an aesthetic connection between the creative process and new technologies determined the path for development of stage design. A technological and creative hybrid created by avant-garde artists brought with it a new aesthetic ideology.

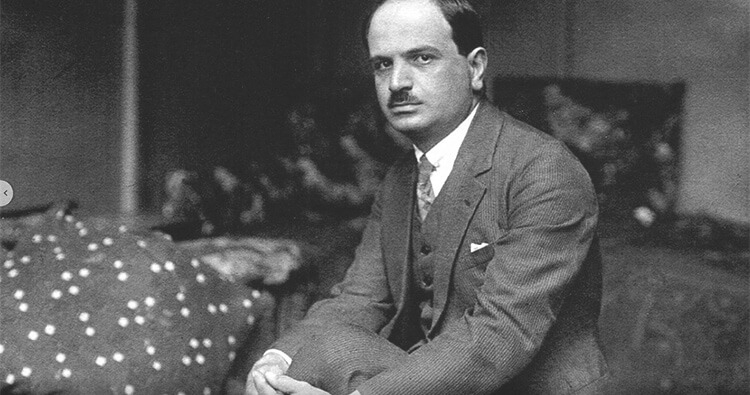

David Kakabadze. National Archive

August 26, 1928: The artist D. Kakabadze arrived. I met him in Paris, where he showed his works at the Salon des Indèpendants. Here he is decorating Hoppla <. . .> They built a construction out of a pile of boxes, but didn’t know how to paint them… David Kakabadze suggested that it would be best to use spray. They tried it out and the method proved to be perfect. The gray costumes will also be spray-painted.

September 4, 1928: Today, we staged the first rehearsal of Hoppla… What a performance!

(Excerpts from the diary of composer Tamar Vakhvakhishvili).

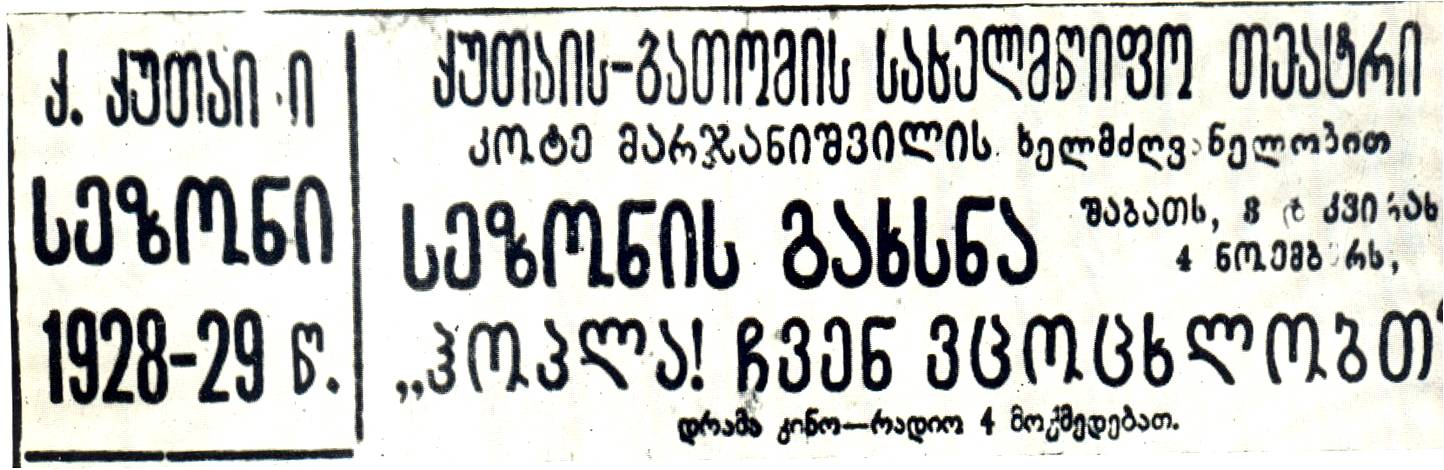

In 1928, the Kutaisi-Batumi State Drama Theatre opened its doors with the performance “Hoppla! We’re Alive.” The stage design was produced by David Kakabadze, who for the first time in Georgian theater made film an organic part of the play.

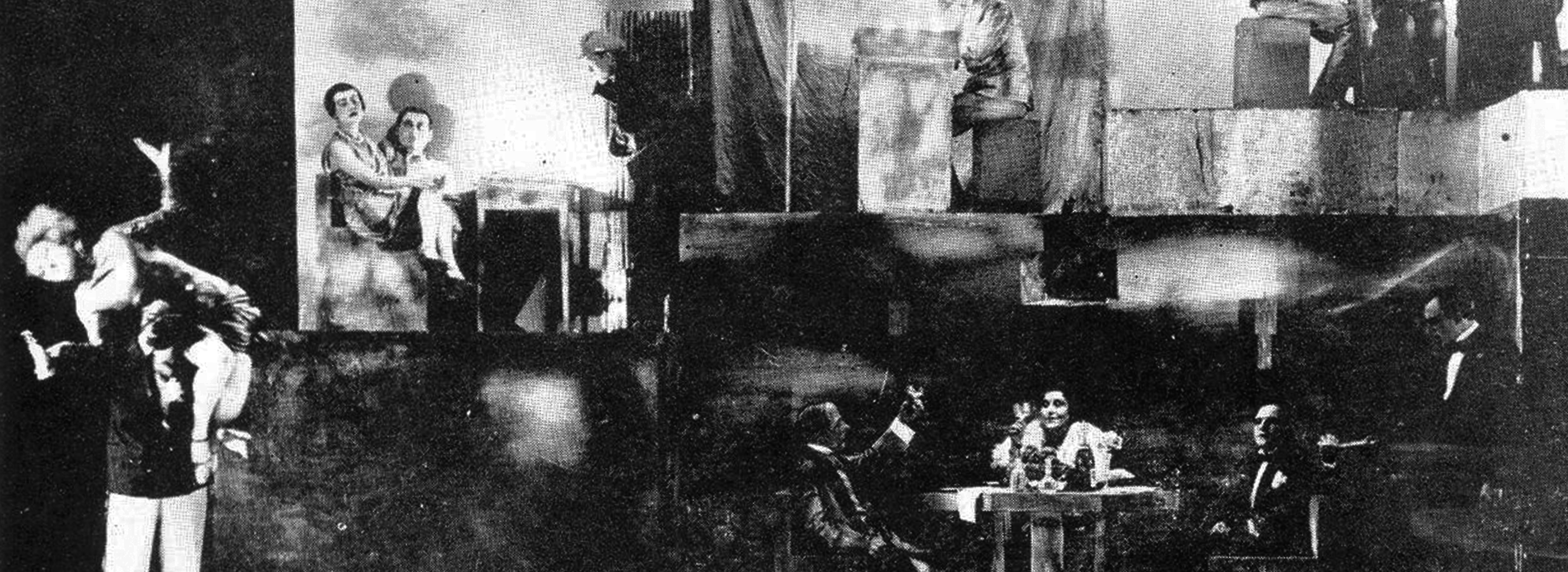

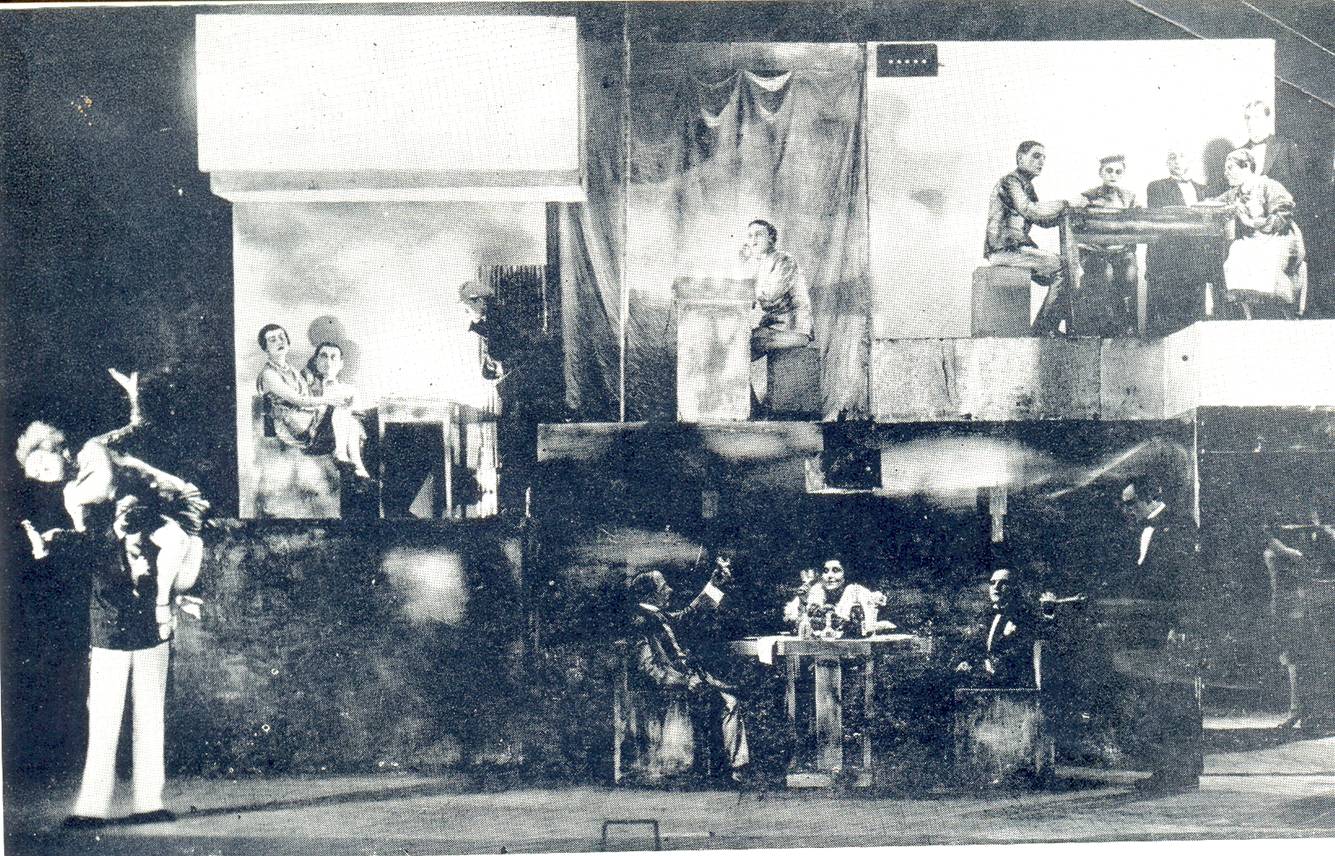

The core element of Kakabadze’s composition was a multilayered construction that consisted of isolated rectangular “interiors”. Its partitions were decorated with mirrors to create the effect of expanding space. Through the use of projector beams, the stage was divided into “film shots,” where the lighting system enabled a rapid exchange of episodes and served as an effective tool for parallel development of the action. ”During the performance one part of the construction remained intact, but thanks to simple changes it was transformed in several minutes from a prison cell into a doctor’s office or a luxurious hotel, a police station, and a prison cell again“.

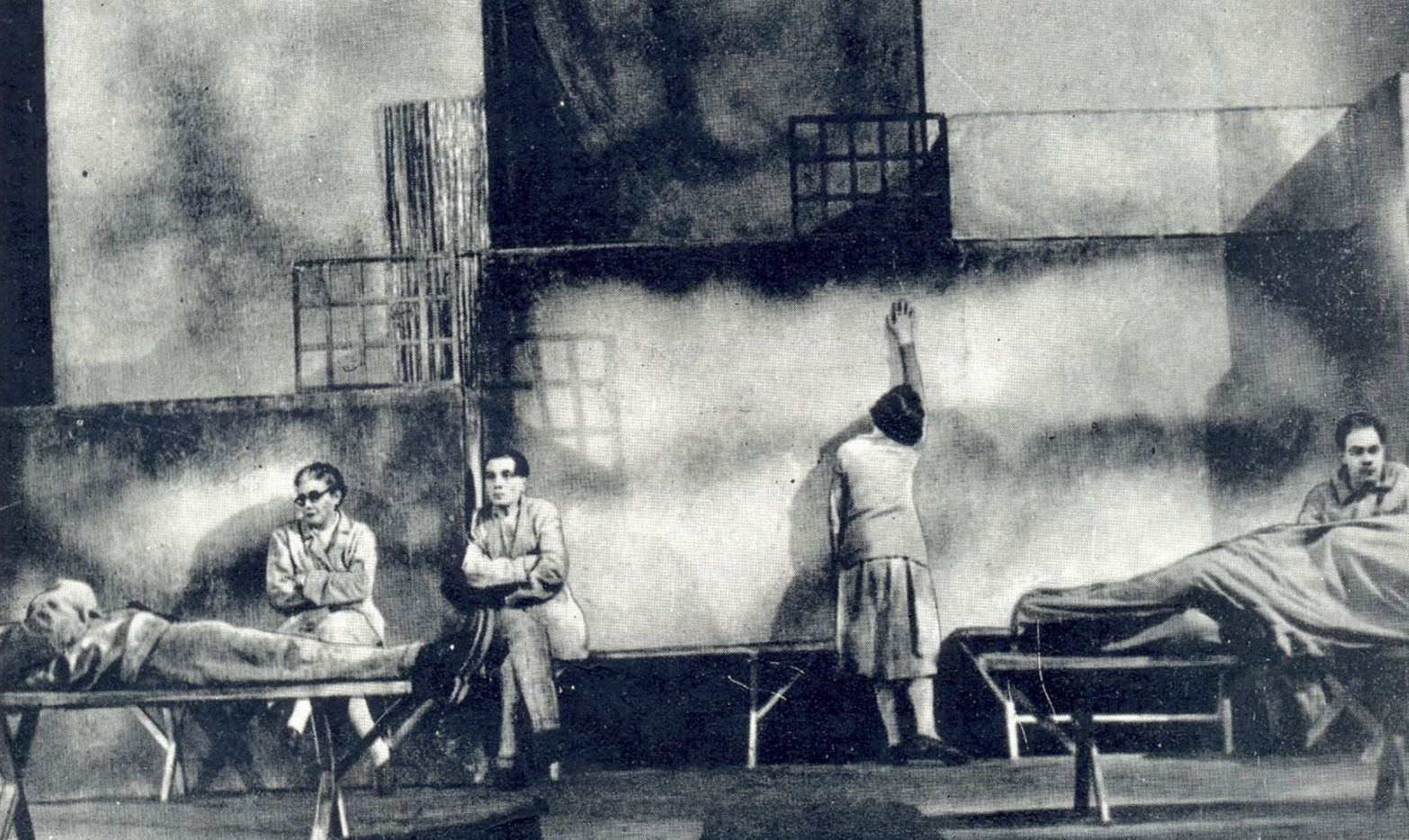

David Kakabadze, “Hoppla!, We’re Alive” (Director: Kote Marjanishvili), 1928. Kutaisi-Batumi State Drama Theatre. Marjanishvili Theatre Museum Archive

David Kakabadze, “Hoppla!, We’re Alive” (Director: Kote Marjanishvili), 1928. Kutaisi-Batumi State Drama Theatre. Marjanishvili Theatre Museum Archive

David Kakabadze added film projection equipment to the stage design. Film shots produced specifically for the performance were projected onto a screen. Action which started in the film continued with the same actors on stage and vice versa, contributing to the dynamic development of a play. In parallel to the movie projection, Kakabadze also used radio recordings – another equally important element of the performance. Different environments including a prison, a minister’s office, a hotel, a restaurant, and a street replaced each other in two parallel dimensions: on screen and on stage at cinematographic speed. Episodes from Ernst Toller’s “Hoppla! We’re Alive” that were shot in open-air locations were directly connected to the events described in the play, and were used to expand and develop them.

Film Shots for the play. “Hoppla, We’re Alive!” National archives of Georgia

David Kakabadze’s principle of constructing his scenographic work was based on a completely new interrelation of space and time, decorations, objects, scenes, and visual images in general, and revealed the artist’s specific attitude to the space. By means of editing, he enriched the content of the composition and subdued the space to it, forcing it to “accommodate” more than the specific space could bear. Synthesis of different disciplines and forms completely changed the structure of the artistic product. Kakabadze’s technological creative hybrid influenced traditional artistic processes, and as a result introduced “new aesthetics” that focused on the reevaluation of traditional notions of time, space, and action with regard to “an indefinite distance and time”

David Kakabadze, “Hoppla!, We’re Alive” (Director: Kote Marjanishvili), 1928. Kutaisi-Batumi State Drama Theatre. Marjanishvili Theatre Museum Archive

David Kakabadze’s stage design for the performance “Hoppla! We’re Alive” was an important cultural and visual sign of a specific time and environment, and clearly revealed the characteristic peculiarities of Georgian Modernism. This performance demonstrated the fidelity, peaceful nature and less confrontational features of Georgian Modernism, which was known for its unity of tradition and innovation, the coexistence of ideologically and genetically diverse and conflicting artistic movements. The typical structure of a decoration system could not contain confrontation, conflict, or an aggressive conjoining of different components (film and theater action). It focused on their coordinated existence, and was based on expedient unity. This is where David Kakabadze emerged as a Georgian modernist.

Sketch for the play “Hoppla!, We’re Alive” by D.Kakabadze. Marjanishvili Theatre Museum Archive

Sketch for the play “Hoppla!, We’re Alive” by D.Kakabadze. Marjanishvili Theatre Museum Archive

If we look back at canonic avant-garde collage (collages by the Cubists and Dadaists) we can observe that it not only concentrated on the discreteness of its integral parts and the existence of sutures and junctions, but presented them as well. David Kakabadze’s stage design, which can also be seen as a scenographic collage, chose a path different from being based on a necessary feature of this artistic method – heterogeneity. He opted to apply a principle of homogeneity in order to pursue the goal of securing uninterrupted development of action through the film shots. Kakabadze’s “flowing” and hybrid “editing” produced a complex associative and conceptual image of creative unity. Based on its form and content it became a representative example of Georgian Modernism.