Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Georgian fine art from the first half of the twentieth century features numerous artists who have vanished from the pages of art history, as well as many outstanding artists who were compelled by the Soviet-era realities to modify their creative creed and identity. Among them, one of the most tragic figures is Irina Stenberg. The particular allure of Irina Stenberg's art, characterized by her boundless fantasy infused with eroticism and intertwined with subtle irony and grotesque elements, once resonated harmoniously with the

Irina Stenberg Crimea. Paper, watercolor. 33.5x24.5

Irina Stenberg. Oriental Women. Paper, mixed media. 18.5x18.5

Irina Stenberg was born in 1903 in Tbilisi. Her family frequently changed residence, living at various times in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Batumi, and Kutaisi. In 1917, following the upheavals of the revolution, the Stenberg family settled in Tbilisi. Irina, who had been exploring fine arts since 1921, pursued her studies at the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts from 1923 to 1928. In 1920, she married Vladimir Andrioletti – an Italian by descent, whose family ran a marble business in Tbilisi. However, the marriage turned out to be short-lived, and in 1924 the couple divorced. In 1929, Stenberg departed for Moscow, where she was to live an interesting and creative life. She became acquainted with the Russian artistic elite, and made friends with members of the group "13." That same year marked the opening of her first solo exhibition in Moscow, which was supported by Lunacharsky. During this period, she collaborated with magazines such as "Рост" (Growth), "30 Дней" (30 Days), and "Крокодил" (Crocodile).

__Rapture_of_Europe_._Paper,_watercolour._45x67._1920s.png)

Irina Stenberg. Rapture of Europe. Paper, watercolor. 45x67. 1920s

In 1930 Irina returned to Tbilisi, where she was confronted with the ideological dictates that were to take effect throughout the Soviet Union during the 1930s. Her work was perceived as bearing signs of bourgeois individualism and subjected to critical scrutiny, compelling the artist to agree to compromise. In 1935, Stenberg's public apology was published in the newspaper "Communist," where she “confessed" that her previous work had been imbued with bourgeois elements. Beginning from the 1930s, Irina Stenberg sought refuge in the theater and publishing, like many modernist artists of her generation. She began collaborating with Georgian publishing houses, primarily focusing on book illustrations. Notably, Stenberg was the first artist to produce a series on the subject of "Women of Georgia." At the same time, she also touched on revolutionary topics, and from 1936 onward, worked actively with various theaters. By a twist of fate, and in keeping with the cynicism of the Soviet regime, in 1943 Stenberg was awarded the title of “Honored Artist of Georgian Art.” Later, in 1976, she was given the title of “People's Artist of Georgia.” The artist wrote about this event in her diary: “this winter I was awarded the title of People's Artist, but strangely it didn't bring me any joy. Now, it's all the same to me. Had this happened earlier... It would have made me happy. What’s more, on the certificate I am inscribed as being 'Vladimir's daughter,' instead of 'Valerian's daughter' – it’s as if it’s not even mine...” The solitary artist underwent a prolonged sense of alienation from herself, her surroundings, and life itself. In the 1950s, she noted in her diary: "It's amusing to contemplate that a mere 100 years separate me from the 50s of the last century! How different things would have been, and how much better I would have felt if I had lived in that era! I would have been surrounded by people similar to myself. Nowadays, I am constantly alone, observing everything from the sidelines. I perpetually perceive myself to be a spectator, much like being in the theater." (Detailed information about the artist's biography and quotes from the artist's diary are taken from the book: N. Gedevanishvili, Irina Stenberg 1903-1984, Tbilisi, 2007, 164, 182.)

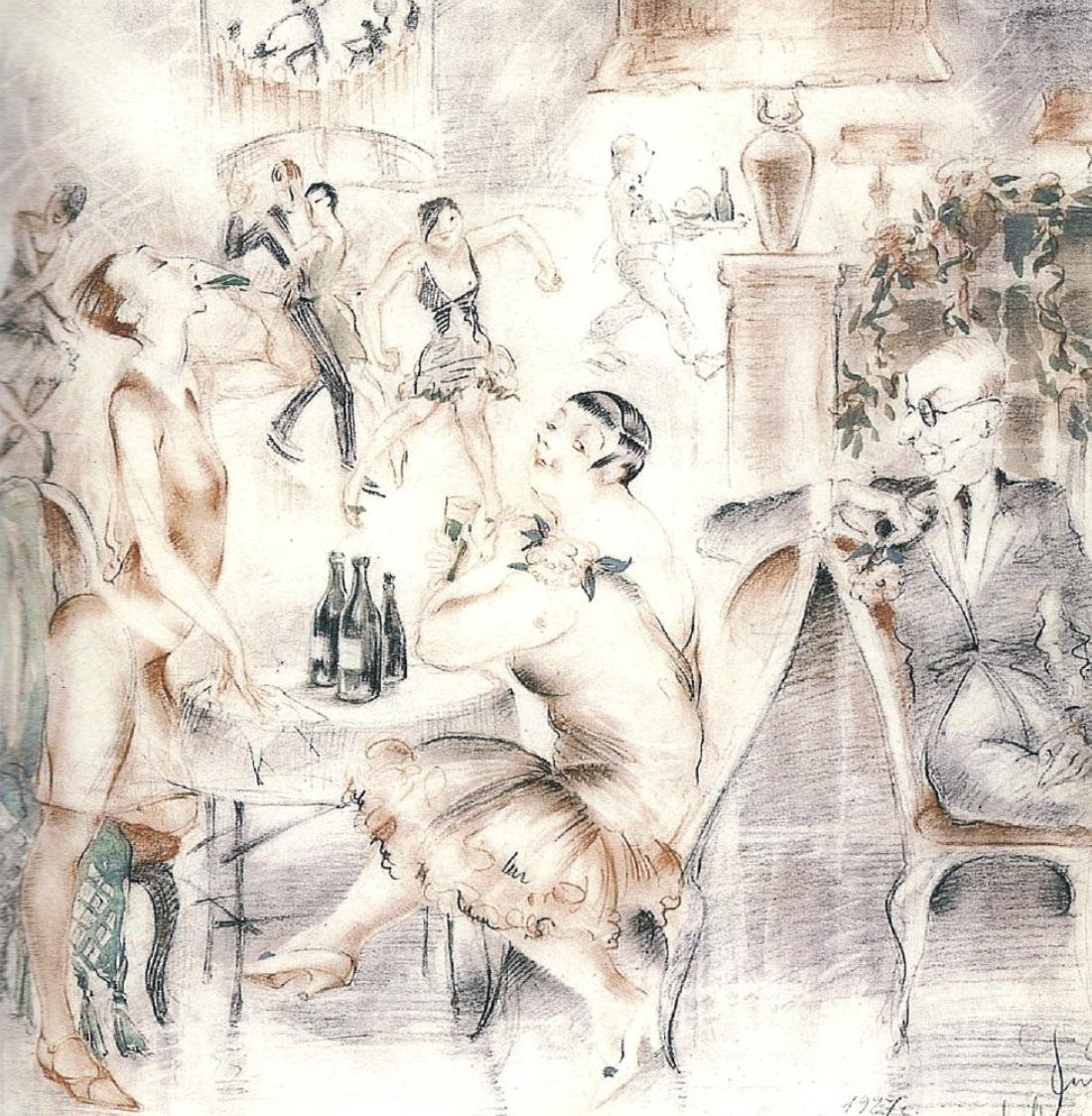

Irina Stenberg. Bacchanalia. 38,5X56. Paper, mixed media. 1920s. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

Notwithstanding her depressive and apathetic mood, Irina Stenberg led an active creative life. As a theater artist, she played a pivotal role in shaping Georgian set design. Nevertheless, the true essence of the artist's identity, and the primary stylistic features that define her work found richer expression in easel paintings – particularly in her artworks from the early period, the 1920s. During those happy times, the artist was not yet constrained by the rigid dogmas of socialist realism, allowing her the freedom to fully explore her feelings, artistic inclinations, and creative pursuits.

__Leda_and_the_Swan_.82x61.Paper,_pencil,_sangina._1926.png)

Irina Stenberg. Leda and the Swan. 82x61. Paper, pencil, sanguine. 1926

Irina Stenberg. A mythological scene. Paper, sanguine. 23x23

In the initial phases of her creative output, Irina Stenberg's paintings are marked by a heightened erotic sensibility. In the works of the 1920s, the viewer is struck by the painter’s vivid imagination and her unabashed declaration of unspoken passions. Notably, the artist herself frequently features as a model in her nude portraits, displaying bold and emphatically erotic poses or “risqué” compositions that are imbued with a narrative character. By integrating within her own self the roles of subject and object, much like Suzanne Valadon, the female artist becomes the subject of passion, and the object or “target” of desire. This duality serves to amplify and structurally complicate the erotic subtext inherent in her artworks. Drawing inspiration from Greek and Oriental mythology (such as "Bacchanalia," "Leda and the Swan," "Adonis and Aphrodite," "Pegasus and the Nymphs," "The Judgment of Paris," and "Variation on an Oriental Theme"), historical figures ("Casanova in Russia"), the not-so-distant past ("Master"), or her contemporary era ("Baths"), Stenberg consistently demonstrated a remarkable ability to interpret narratives through an erotic lens. Her artworks boldly depicted the sexuality of provocatively portrayed figures, going beyond the boundaries of the forbidden. The "self-sufficient eroticism" that emanates from the female characters in works such as "Leda and the Swan" and "The Abduction of Europa" is deserving of particular attention. Notwithstanding the mythological plot, where Zeus assumes the form of a swan to seduce Leda, the love scene between the woman and the bird is perceived less as zoophilia and more as an expression of self-gratification. Generally speaking, the source of eroticism in Irina Stenberg's paintings is unequivocally the female body. The male form appears as a "secondary event," subject to her will and control, occasionally portrayed in a somewhat comical light, as seen in works such as "Passion." Irina Stenberg's artistic reality is uncompromisingly bold and honest, with eroticism persisting even in the presence of grotesque elements and irony that act as "impartial arbiters." Furthermore, Stenberg frequently utilizes self-irony in order to add another layer of complexity to her works. At the same time, the artist seems to be attempting to challenge us; encouraging us to play an "immoral" game in which she manifests a disregard for all social conventions and accepted standards of behavior.

__Untitled_._Paper,_watercolour._29.5x31.5._1926.png)

Irina Stenberg. Untitled. Paper, watercolor. 29.5x31.5. 1926

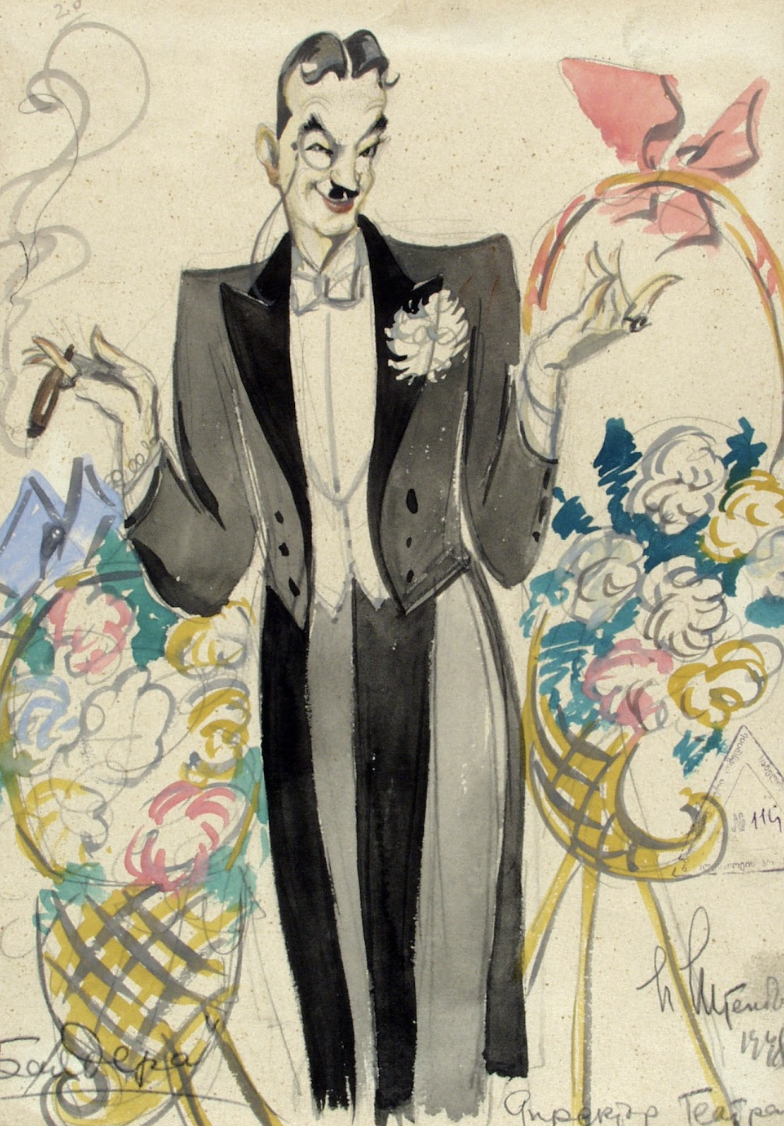

The pathos of erotic self-expression is significantly reduced in her works that date from the 1930s. In the paintings produced at that time, eroticism either vanished completely or was subdued and subjected to certain frameworks. The exaggerated grotesqueness of the forms softens the effect. The visually striking humor of the characters or situations "devalues" eroticism and lessens its significance, which may be perceived as a compromise – a kind of apology on the part of the artist. From this time on, comedy and irony became not only an artistic method, but also a mechanism by means of which Irina Stenberg "adapted" the subject matter to make it more accessible and understandable for the average Soviet citizen. While the artist had previously explored this theme through various interpretations that employed grotesque and irony, later on she began to offer a critical assessment using those same elements. Oftentimes, the composition was loaded with negative connotations, thereby effectively "neutralizing" the erotic theme.

Irina Shtenberg. Cafe-chantaine - From Nep Series. Paper, mixed media. 32x32. 1929-1930. Georgian National Museum

Irina Stenberg (1903-1985)

For instance, in her works from the 1930s, eroticism is consistently intertwined in the plot with alcoholism, portraying it as a "side event" and negative outcome (as can be seen in the "Nepi" series). In this manner, the painter assumed a didactic role, which was entirely foreign to her but deemed acceptable by the Soviet authorities. The subtle erotic sensuality that had characterized her works from the 1920s was irrevocably lost, making way for caricatures that are infused with light humor. Had it not been for Irina Stenberg's inherent artistry, discernible inner wisdom, and undeniable talent, this phase of her artistic journey would have appeared dull and vulgar.

._Blue_African_Woman._Mixed_media_(watercolor,_Indian_ink_and_coal)_on_paper._43x21cm._1930._.png)

Irina Stenberg. Blue African Woman. Paper, mixed media (watercolor, Indian ink and coal). 43x21. 1930. This work is part of ATINATI Private Collection

In constant conflict with herself, Torn between her innate artistic dispositions and the constraints of reality, in the late 1930s the self-denying artist shifted her direction to the field of theater. Irina Stenberg, described by Nino Gedevanishvili as a "former dissident of aesthetics," sought refuge in the theater. Here she could continue to work her magic, with ample room being provided for her imagination. While her focus shifted away from eroticism, she undoubtedly retained the ability to craft an impressive spectacle.

Irina Stenberg. Stage Design by Ch. Aitmatov. "The girl in the red scarf". Staged by K. Surmava. A. Griboedov Theatre. Paper, mixed media

Irina Stenberg. Costume design by A. Ostrovsky "Profitable place". Paper, mixed media. 32x20.5. Staged by A. Smiranin. A. Griboedov Theatre

Irina Stenberg. Costume Design by I. Kalman "Bayadere". Paper, mixed media. 29x20.5. Staged By D. Dzneladze. Music And Drama State Theatre

Nevertheless, during the latter period of her life, the artist gradually distanced herself from her surroundings and withdrew into herself. With advancing age, it appeared that she grappled more and more with the sense that she wasn’t able to fully unfold or realize herself. The repressive realities of the time when she lived seemed to deny her the opportunity for complete self-expression, and in exchange for physical safety she was compelled to transform her artistic identity.

Irina Stenberg. Self-portrait. Paper, sanguine. 22.5x15.5

In 1985, Irina Stenberg passed away in her home, aged 82. Her oeuvre will forever remain as a story retold in the annals of fine art, recounting the tale of this gifted artist whose creative freedom was constrained by the shackles of a totalitarian regime.