Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Solomon Gershov (სოლომონ გერშოვი) was a Jewish artist from the Soviet Union and a representative of nonconformist art. These words themselves imply the inevitable dramatic development of Gershov’s life and creative work. All Jewish artists in the Soviet Union were possessed of a dual identity, and they continually needed to adjust to a different way of life, feeling like aliens in the world of art and not only.

In 1919, the Jewish avant-garde painters Issachar Ber Ryback and Baruch Aronson wrote in their co-authored essay The Paths of Jewish Painting: Thoughts of an Artist, "The artist is doomed to solitude." This phrase most accurately characterizes the life of Solomon Gershov.

Born in 1906 in Dvin (present-day Daugavpils, Latvia), Solomon grew up in the religious family of a devout Jew, his father Moshe Gershov. The Gershovs' home stood next to the synagogue and the cemetery. Every day the young boy observed sad processions filing to the cemetery. This feeling of the tragedy of life did not leave him, even after the family moved to Vitebsk. His memories of the persecution and massacre of Jews did not fade without leaving a trace, and later resurfaced under various interpretations in the artist's work. "Some time in 1919, I remember 40 sleds on which were placed, under burlap, the corpses of Jews that had been killed by gangs of Whites somewhere on the outskirts of Vitebsk. A long line of hearses that stretched almost one verst, accompanied by frightened and incensed Jews, was headed towards the Zaruchie cemetery... Nothing disappears without a trace, especially at an age when the personality is being formed; one may be affected more, another less," the artist wrote in his memoirs.

Solomon Gershov had evinced a passion for painting since boyhood, despite the fact that his extremely religious parents disapproved, and would use his paintings as kindling to start the fire. According to the artist, this was not done out of malice, but simply because they did not appreciate the significance of his paintings. Gershov studied both at state school and theological seminary – where students were trained for the rabbinate – but his desire to paint won out, and he was soon enrolled at renowned artist Yudel Penn's school in Vitebsk. Although Penn himself was a follower of the academic school, it was through his support that the most powerful avant-garde center of Jewish artists was formed, the goal of which was a synthesis of ancient Jewish culture and folklore with the artistic language of the avant-garde. Judaism, as a cultural phenomenon based on a system of moral principles, was the preferred starting point for Jewish modernist artists. The key point for the Jew, who had been expelled from his native land for ten centuries and was destined to spend the rest of his life searching for it, is the eschatological concept of death and salvation. These artistic and spiritual values can also be observed in the works of Jewish modernist artists. In artworks by Issachar Ber Ryback, Boris Aronson, Marc Chagall, and Solomon Gershov, one can perceive a metaphorical worldview; the transformation of everyday life into a mystical, imaginative, and fabulous membrane, the loading of each story with something more than just a simple motif, in which boundless sadness, kindness, and childlike sincerity intersect, and something else that cannot be expressed verbally strikes deep spiritual chords in the viewer. Thus, Gershov undertook his studies at the excellent art school of the Vitebsk Free Art Studios where, among other outstanding artists, Robert Falk, Kazimir Malevich and Marc Chagall were engaged as instructors. In 1922, Gershov left for St. Petersburg (then Petrograd) to continue his studies, and enrolled at the Drawing School of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts. From 1925 to 1927 he studied at the "Analytical Art" school of Pavel Filonov, although Gershov had a completely different artistic vision from Filonov's "analytical art" and was even expelled from the school.

Solomon Gershov. Morning. 27.5X21.5. Paper, gouache. 1970

Solomon Gershov was compelled to change his name and surname; his Soviet passport identified him as "Alexander, son of Mikhail" rather than “Solomon, son of Moses. Additionally, despite his proficiency in Yiddish, Gershov had to learn the Russian language. He was prolific in various artistic genres, and an exhibition of his works was held in St. Petersburg (by then renamed Leningrad). However, in 1932 Gershov was arrested and exiled to Kursk. The works that were confiscated from his house when it was searched were never returned to the artist. Gershov was not the only one swept up in these tumultuous twists of fate; the left-wing poets Daniil Kharms and Anatoly Vvedensky were also forced into exile in Kursk. With the assistance of the Soviet painter Isaak Brodsky, Gershov managed to return to Leningrad. Declining offers from official organizations to collaborate, he followed a friend's advice and moved to Moscow, where he enjoyed a rather successful creative life. Robert Falk, who was not only an exceptional artist but also a profound erudite, played a significant role in the development of Gershov's artistic taste. For quite some time, Falk represented a prominent figure within the first wave of the avant-garde art movement.

Solomon Gershov. In the circus. 29.5X25. Paper, gouache. 1970

Solomon Gershov. Dance. 29.5X25. Paper, gouache. 1970

Despite the fact that Gershov had taken part in the second world war and had worked for a military newspaper, in 1948 he was arrested for a second time. Gershov was sentenced to nine years’ hard labor in the mines of Vorkuta and Inti. It was tragic that Gershov's family renounced him. Solomon Gershov's paintings were once again confiscated from his home. As a result, it is rather difficult to judge his avant-garde works, though it is possible that he was far removed from radical avant-garde explorations, and in his works he always maintained an awareness of the real world. The majority of his paintings depicted victims of tyranny. In his view, painting was an act of resistance against a reality that had denied him the opportunity of living a normal life. The Soviet authorities established the standard, and penalized people who held divergent opinions. This was generally the fate of persons who thought differently, or who just acted a little more freely. Their destiny united them, and although some of them became discouraged, Gershov was able to withstand all these blows. "I did not imagine that all this was happening to me. I observed myself from the outside," wrote the artist in his memoirs, but the feeling of sadness that permeated his entire oeuvre never disappeared.

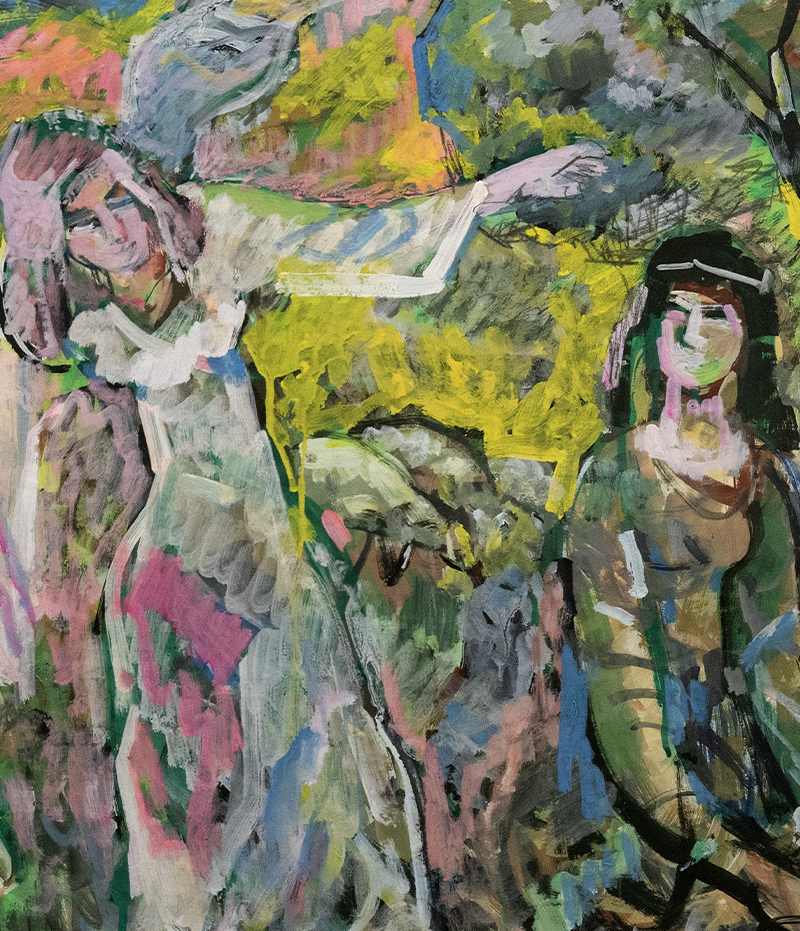

Solomon Gershov. An illustration of the story of Babel. 20X18.5. Paper, gouache. 1970

Solomon Gershov. Beethoven and Juliet Guichard. 68X58. Paper, tempera. 1977

Gershov returned to Leningrad from exile after "Khrushchev's Thaw" in 1956, and had to begin all over again. His works were inspired by Jewish celebrations, his childhood recollections of Vitebsk, and biblical themes that he reinterpreted in new artistic forms. Portraits, landscapes, ballet and circus performances served as pictorial representations of his life, impressions, and sentiments. The music of Shostakovich was also a source of inspiration. Gershov, a lover and connoisseur of classical music, frequently featured prominent composers in his portraits (see, for example, his Beethoven and Shostakovich series). Gershov was a master of improvisation. He matched the simplified, conditional form of the image with the pictorial and sketchy manner of writing. The temperament of the structure of his works is based on an emotional worldview. Gershov worked using different materials, frequently blending tempera, watercolor, gouache, foil, and Japanese paper in his artworks. The expressiveness of his pieces is often heightened by the texture of the painting’s surface. Through the synthesis of materials and the harmonious interplay of colors, the artist achieved a remarkable expressiveness. Each of his works radiates a distinct sense of individuality. "If I had not been a Jew, as I understand it, I would not have been an artist, or I would have been a totally different kind of artist," wrote Gershov. His works were known within a narrow circle – the so-called ‘brainy intelligentsia,’ but were completely unknown to broader society. Gershov often participated in exhibitions, but his name never appeared in the press, and no critics discussed his work. This was one of the methods of Soviet censorship: behaving as if the artist did not exist at all.

Like many other non-formal artists, Gershov's paintings were exhibited at numerous locations around the world after being sent overseas via diplomatic channels with the assistance of Herbert Marshall.

Solomon Gershov's art was distinctly unique. Neither social realism nor the artistic styles of the 1960s can be discerned in his work. Gershov appeared as a link in the violently broken chain that connected 1960s nonconformist art with the Russian avant-garde.

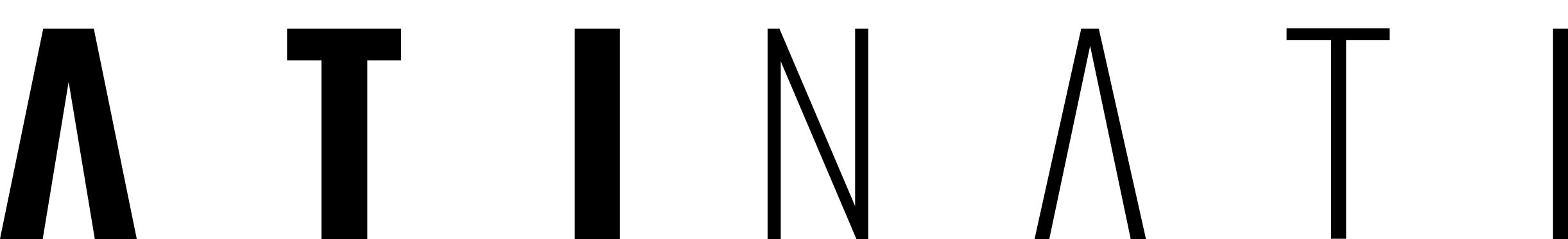

Solomon Gershov. Three graces. Paper, tempera. 70X68. 1980s

Solomon Gershov. Old man. 29.5X25. Paper, gouache. 1970

Solomon Gershov enjoyed a particularly close, friendly and creative relationship with Georgia. The artist spent time residing in Tbilisi during the 1960s. Just as in the heyday of Georgian modernism, at that time Tbilisi remained a relatively free place to live. During this era, Georgian themes and motifs played a significant role in the artist's work. In particular, the cycle honoring Pirosmani merits consideration. He shared many of the great Georgian artist's sentiments, including his outlook and humanism. Georgia also loved and appreciated the artist. All researchers of Gershov's creative work attest to the particular closeness of the artist to Georgia, and the fact that Georgia understood and appreciated Solomon Gershov as a person and as a creative spirit. This was perfectly natural. The creative challenges that Georgian fine art had encountered from the 1960s onwards in terms of modernizing the expressive language were in line with the artistic tenets embodied in Gershov's life and work.

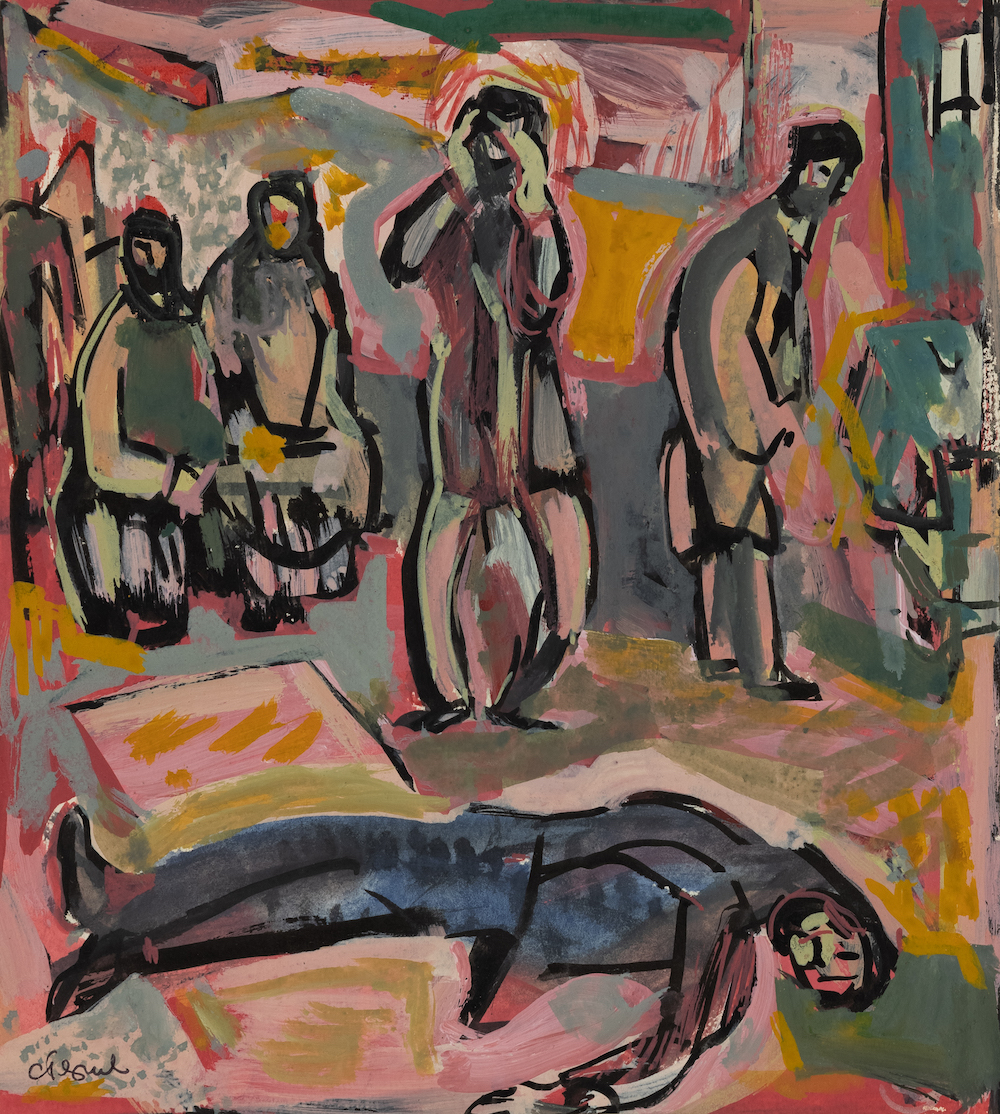

Solomon Gershov. A composition on a Georgian theme. 73X60. Paper, tempera. 1980s

Solomon Gershov.Georgian still life. 60X82,5. Paper, tempera. 1970s

Gershov organized a number of exhibitions in Tbilisi and Kutaisi during the 1970s, including one at the State Museum of Art. As a result of these exhibitions, many of the artist's pictures were preserved in private collections and the Shalva Amiranashvili State Art Museum.