Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

The formation and evolution of socialist realist art in Georgia commenced during the 1930s and 1940s. However, its ideological foundations in Russia were seen between 1922 and 1932. Critical realism (peredvizhniks), constructivism, neoclassicism, and French classical realism conditioned the eclectic visual language typical of socialist realism and its utopian ideology. The non-figurative, unrealistic artistic trends in Russia, which pursued a revolutionary ideology under the auspices of Lunacharsky, lost relevance for the Bolsheviks, since such art lacked a sense of realism and simplicity of expressive language. For the Bolsheviks, the ideal of art had to be figurative, implying socio-political significance; in short, it had to be easily understood by the working class. The control of the cultural sector, including art and humanities, was centralized under the People's Commissariat of Education. Painting, architecture, and plastics acquired state significance, implying a model of politicized art that agitated communist politics in a language comprehensible to the people.

In Russia, from 1922 to 1932, numerous artists' associations were formed, including the New Society of Artists, the Society of Easel Painters, and the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia. Easel painting became the predominant medium in Soviet visual art, serving as an anti-position to avant-garde and multimedia modernism. There were well-marked differences between the Society of Easel Painters and the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, characterized by stylistic and ideological differences. Representatives of the Society of Easel Painters depicted themes of industrialization, sports, and urbanization, following a more modernist experience. Conversely, members of the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia focused on documenting existing realities or adhering to the critical-realist traditions of the Peredvizhniks. The ideology and expressive language of this group became the cornerstone of socialist realist painting. According to Andrei Zhdanov's doctrine, the novelty of socialist realism lies not in portraying objective or even critical realities, but rather in depicting the existing reality within the context of revolutionary progress. The prevalence of easel painting promoted painting as a tool of propaganda, leading to the emergence of four thematic trends in painting during the 1930s-40s: "Proletarian" painting primarily portrayed the heroic image of the worker and had to possess distinct figurative expressiveness for the working class audience; "Typical" type canvases depicted scenes from everyday life; works of the "Realistic” type aimed to be convincing and representative; while "Guerrilla" type paintings portrayed victories in the Second World War, or featured pathos-laden historical battle themes.

The variety of genres, typological aspects, diverse ideologies, and the mosaic of artistic thoughts and traditions were all geared towards shaping the "new working man." This envisioned figure would stand in opposition to capitalism and fascism, aiming to leave an indelible mark on the rise of a utopian-phantasmagorical state. However, the unitary space of the Soviet Union, prioritizing socialist and non-existent realities over critical-objective realism, was doomed from the very beginning.

Georgia, serving as a significant cultural and political center, fell under the influence of socialist realist art and ideology. In 1921, the Bolsheviks started reorganizing the Georgian Society of Artists. Georgian modernism and its representative formalist artists were unacceptable for communist ideology, which identified non-figurative, avant-garde painting with the bourgeois-capitalist world. The cause for the persecution was the incomprehensible language, which was less expressive and less well perceived by the working class. Mose Toidze founded the Proletkult (proletarian culture) studio, providing an opportunity for individuals from all social layers to learn painting. Irakli Toidze joined the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia and began making propaganda posters.

Easel painting remained significant in Georgia, leading to the establishment of the Association of Revolutionary Artists, similar to the Society of Easel Painters and the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia. Later, the Association of Revolutionary Artists was labeled as a union of petit-bourgeois painters, leading to its losing significance. Additionally, "SARMA" was another union whose representative artists were separated from the Georgian Artists' Society. Their artworks depicted stylistic and ideological aspects typical of social realist painting. Subsequently, the Georgian Academy of Arts transformed into the Technical Academy of Arts, before ultimately being shuttered.

Georgian socialist realism, as a politicized art form and propaganda tool, was a counter-response to the socio-political and cultural situation ongoing in the country.

A brief overview of Georgian socialist realist painting (from 1921 to 1950):

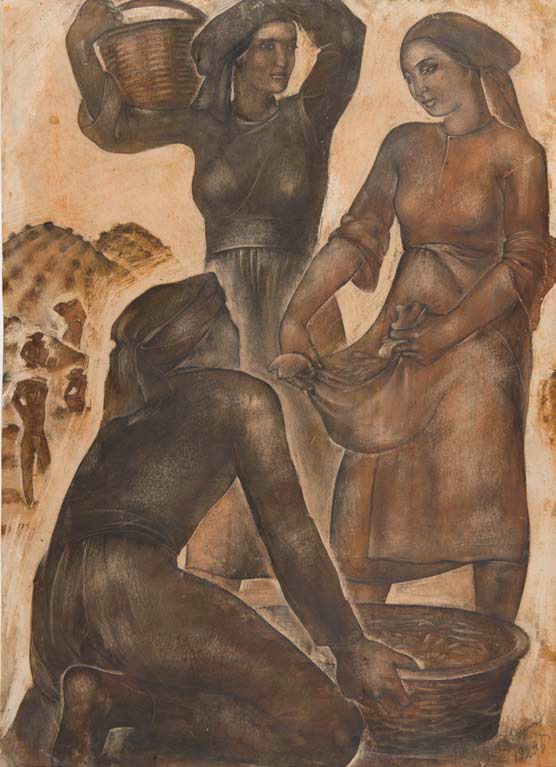

Tamar Abakelia (1905-1953) was a theater and film designer, illustrator, graphic artist, and sculptor. She was a member of "SARMA" and the Georgian Artists Union. Her painting Tea Picking 1 depicts a typical social realist, proletarian genre. It shows three female farm workers engaged in the process of harvesting. The artist focuses on the female workers through the hieratic relation of their bodies and baskets to the work space. The workers' figures are extensive. Narratives and myths about the hieratic features of the "act of labor" followed a similar stylistic pattern. Abakelia's figures, with their hieratic scale, tonal-chromatic gradation of brown, and the setting principle, give the impression of a high-relief frieze. With the exception of facial characteristics, draped clothing, and baskets enclosing the harvest, the whole visual plane is conventional. Workers harvesting crops on the hills are represented in a fragmented, reduced size in the painting's left-hand middle register. Stalin's Speech in Batumi 2 displays a leader lecturing to a crowd on the beach. The narrative of heroism and leadermania is overshadowed by a laconic tone and almost achromatic colors. The facial expressions of the leader, the person in the helmet, the men standing in the front rows, and the realism of the figures harmoniously interact with the abstract urban background and conventional figures lost in depth.

Tamar Abakelia. Tea Picking. Sanguine on paper. 1929. 49.5x35.5

Tamar Abakelia. Stalin's Speech in Batumi. Sanguine on paper. 52.5x60

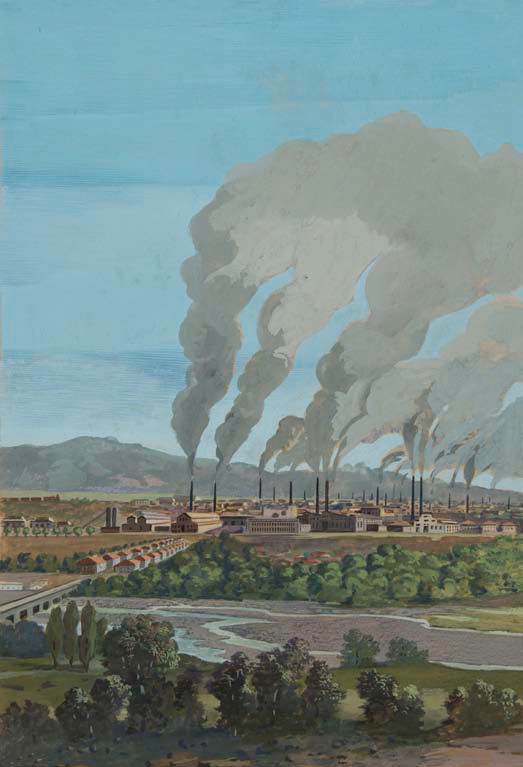

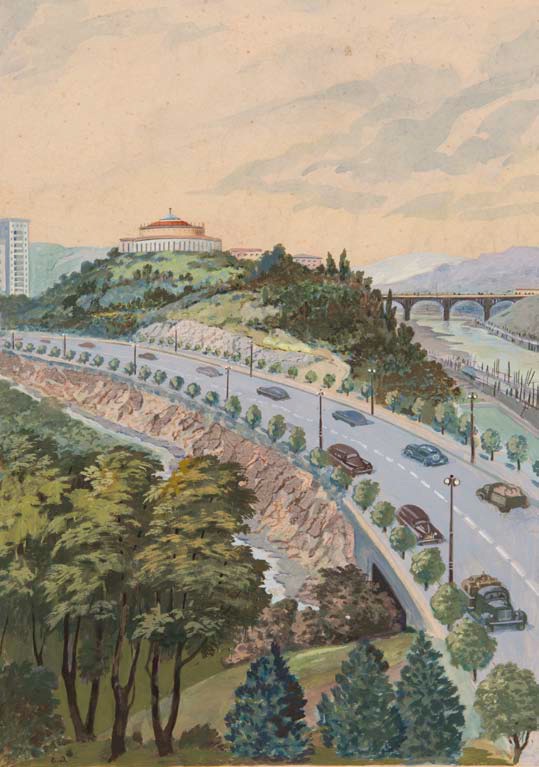

Severian Maisashvili's (1900-1980) creative work unites painting, graphics, and miniature. The work Laying Rails 3 is thematically similar to the works of the proletarian everyday-life scene; however, due to the specifics of the fine art language, it speaks of a more subjective style and manner. The relationship between Maisashvili's individualistic micromodel and realistic narrative does not clearly intersect with socialist-realism classicism. Conventional space, altered scales and proportions, and an experimental perspective are quite enough to stylistically identify the author with modernism. The thematic line of the work and the scanty monolithic color provide limited options to perceive the work from a socialist-realist perspective. The uneven hills, laid rails and rock ledges are all portrayed in a planar form. Distorted figures, a child staring at them and their grotesque posture, reveal a connection with caricature and theatrical painting. The urbanization and industrialization of Georgia is clearly depicted in the bolder and more realistic works that are painted in colors characteristic to Severian Maisashvili: Rustavi Metallurgical Plant 4 and New River-Bank 5. Both works portray the architectural transformation of Tbilisi and Rustavi with remote views. The artist does not depict the workers or the pathos of the construction: He chooses the symbiosis of architecture and nature, which gives rise to a feeling of calmness and rationalism.

Severian Maisashvili. Laying Rails. Pencil and sanguine on paper. 1930. 25.5x36.5

Severian Maisashvili. Rustavi Metallurgical Plant. Gouache on paper. 42-30

Severian Maisashvili. New River-Bank. Gouache on paper. 43x31

Korneli Sanadze (1907–1985) was a painter, graphic designer, theater and film artist, and active member of the Association of Revolutionary Artists of Georgia. His artwork was frequently on display at the exhibitions of the republic of Georgia. Thematically a social realist painting, Portrait of Stalin 6 has a color and tonal-chromatic gradation appropriate for the somber mood typical of Soviet-era Georgian painting. Joseph Stalin's three-quarter profile is shown on the left side of this image plane. The image of the leader is hieratic in the background. Stalin's facial expression, features, and attire are represented in greater detail than the flanking throng going uphill, the commander holding a red flag, and the mountains. The expressions of the latter figures are highly conditional and vague. The monolithic brown gradient is accented by dark yellow, red, green, and blue. The simulation of mass dynamics and the accentuation of the red flag clearly reflect the spirit of Soviet pathos. The picture plane presents a kind of atavistic sign language of modernism. The modernist or experimental image is determined by rough, intense strokes, expressiveness of colors, a subjective attitude and convincing collation of realism with an abstract background. The sense of realism or believability from the given canvas is not created by imitative representation, but by the traces left as a result of artistic formation on a two-dimensional surface. Leisure 7 displays a proletarian topic. In this case, the artist reacts to the social realist program with a thematic line; yet, it is not right to seek conditionality, subjectivism, and formalism in any type of realism. Intense strokes are used to depict tired workers, carts, big trees, and mountainous terrain. The painting's surface reflects the artist's experimental pursuit of emotive color and limitless forms. Classical-objective, particularly idealized realism, is less readable. Similar stylistic features apply to Mowers 8 and Ajarian Tea Picker 9. Korneli Sanadze and numerous artists from the SARMA-REVMAS group were at a creative crossroads, falling conceptually into social-realist circles, but adhering to more western fine art language traditions.

Korneli Sanadze. Portrait of Stalin. Oil on canvas. 70x70. the 1930s

Korneli Sanadze. Leisure. Oil on canvas. 68x68. 1939

Korneli Sanadze. Mowers. Oil on canvas. 1931

Korneli Sanadze. Ajarian Tea Picker. Oil on canvas. 1931

Ucha Japaridze was a painter, illustrator, and graphic designer who lived from 1906 until 1988. He went to Oni and temporarily put his studies at the Academy due to financial difficulties. After coming back to Tbilisi, he joined SARMAS. The artist began working in the State Museum's ethnographic section, and actively took part in scientific expeditions. That is why he produced a series of ethnographic works in which the national motif undermined the idea of socialism. Compared to his earlier pieces, The Red Army Soldier at the Collective Farm 10 is more colorful and diversified. The group gathers around the Red Army soldier during a field break, where he reads the workers the latest news from a newspaper. Japaridze, just like Abakelia, is drawn to citing experiences from the Baroque and Renaissance. This is exemplified by the way the compositional center is captured, how the triangle shape is arranged, and how expertly the perspective is constructed. The proletarian line is represented by the laborers' plump bodies, rather exaggerated voluminous forms, and their uniformity. The Call of Loneliness 11 is a highly emotive piece of art. The yoked buffalo is hieratic compared to the mountain hills, trees and houses in the background. The trapped animal does not have enough verticality of the picture plane for an expressive, inner cry. The composition's emotional layer is represented by the sky, which is broken up by a tonal-chromatic gradation in dark blue. This canvas is an allegorical representation of incompatibility with Soviet Russia's rule, conveyed through an animalistic depiction of anthropocentric origins.

Ucha Japaridze. The Red Army Soldier on the Collective Farm. Oil on canvas. 1933. 84.5x130

Ucha Japaridze. The Call of Loneliness. Oil on cardboard. 1930. 32x33

Mose Toidze (1871–1953) was a painter and graphic designer. He was a free listener at the St. Petersburg Art Academy, where he studied under Ilya Repin. He took part in the Peredvizhniks’ 31st spring exhibition. After returning to Georgia, he established the People's Art Studio and the REVMAS group of artists. He taught at Tbilisi Academy of Arts. Toidze's social realist canvases are more influenced by the Soviet art program than anything else. The artist linearly presents the concepts of socialism, possibly from a Bolshevik perspective.

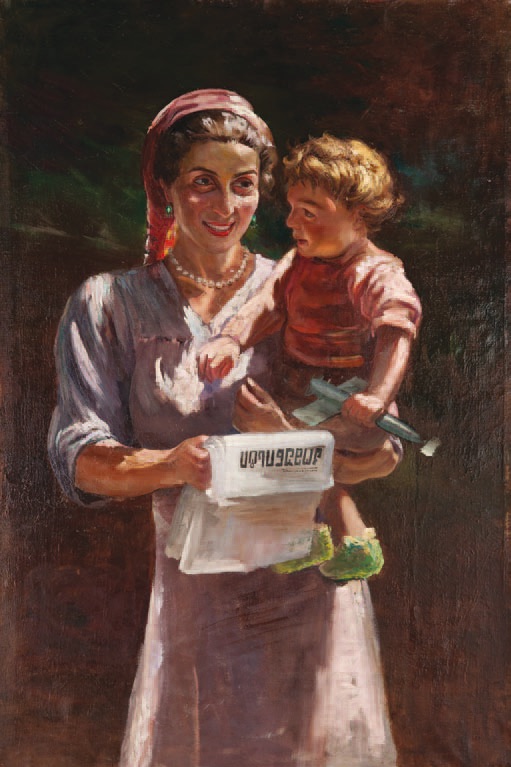

Stakhanovtsi (Industry) 12 is created in a social realism-inspired academic style. In the work, through meticulous construction of the proletariat narrative, a visually idealized realism is achieved. The athletically built workers are depicted against the background of a powerful factory, the limited colors depicting the dynamics of work. In this work, Mose Toidze employs idealized impressionistic lighting as a stylistic device. The factory that transforms into a shimmering imitation of light, a moment that is fixed, and movement that is captured on canvas, creates something that is perceived as an “impression.” Happy Life 13 – here, based on the title and the idealized, sugarcoated expression, the pro-socialist attitude of the artist can be seen. With the collective members' false or illusionary smiles, the canvas portrays the harvest process. This work cannot be considered realistic in any way. The photographic mimicry and "illustrativeness" of the proletariat living environment suggest a connection to kitsch animal art. We can consider Toidze's Ours Are Winning 14 in an identical light. A mother, a member of the Collective, is seen with her infant son against a traditional background and impressionistic lighting. Photogenic, sugarcoated faces are displayed under the play of light beams. Through the printed copy, Mother finds out about the Soviet Union's victories in the war. The last detail, which shows a little boy holding an airplane, is crucial to understanding the Soviet pathos. The child is thought to be the cornerstone of the Soviet Union, whose formation as the country's protector begins while playing.

Mose Toidze. Stakhanovtsi (Industry). Oil on canvas. 141x171

Mose Toidze. Happy Life. Oil on canvas. 121x142

Mose Toidze. Ours Are Winning. Oil on canvas. 135x91. 1940s,

The war genre is less prevalent in Georgian art in contrast to Russian. Irakli Toidze, like his father, looks at the art of socialist realism with empathy; he believes in it. His works are created in the mold of pathos and kitsch. Guerrilla painting became relevant in social realism as an agitation program during the Patriotic War. Irakli Todze's Motherland Calls Us 15 serves exactly this order. A highly artistic lithographic poster presents a woman, a member of the Collective, as a good citizen. She wears a scarlet outfit, has a ferocious look, is flanked by bayonets, and calls Soviet citizens to patriotic war. The picture of the woman holding a military pledge radiates a "programmed" civilian sensibility, which is reinforced by robotic bayonets devoid of warrior figures. Toidze, like his father, leveled national creative traditions, as demonstrated by changing Soviet citizens' ethnic origins into a cosmopolitan appearance.

Irakli Toidze. The Motherland Calls Us. Lithography. 88.8x59. 1941

Ivane Vepkhvadze's work, Battle 16, features a multi-figure battle scene from the Russian Patriotic War. Behind the conventionality and surging energy, Slavic domes, Soviet flags, and uniformed troops are seen in a bleak snow-covered terrain. However, the battle pathos is less obvious because the varieties of fighting calls or accents are determined by conditionality. The main element is the realistic narration of fighting dynamics. Ivane Vepkhvadze opposes the filigree story of Russian social realist painting, as well as the fine marks of the realist style.

Ivane Vepkhvadze. Battle. Oil on cardboard. 26.5-50. 1943

Social realist painting clearly illustrates the projection of utopian Bolshevik ideology or Soviet mythology. From 1921 to 1950, Georgian painting avoided both the fabrication of national ideals and cosmopolitanism. Despite the rather diverse artistic milieu in Sovietized Georgia, most artists associated Soviet culture with an undesirable and inorganic fine-doctrinal program.