Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

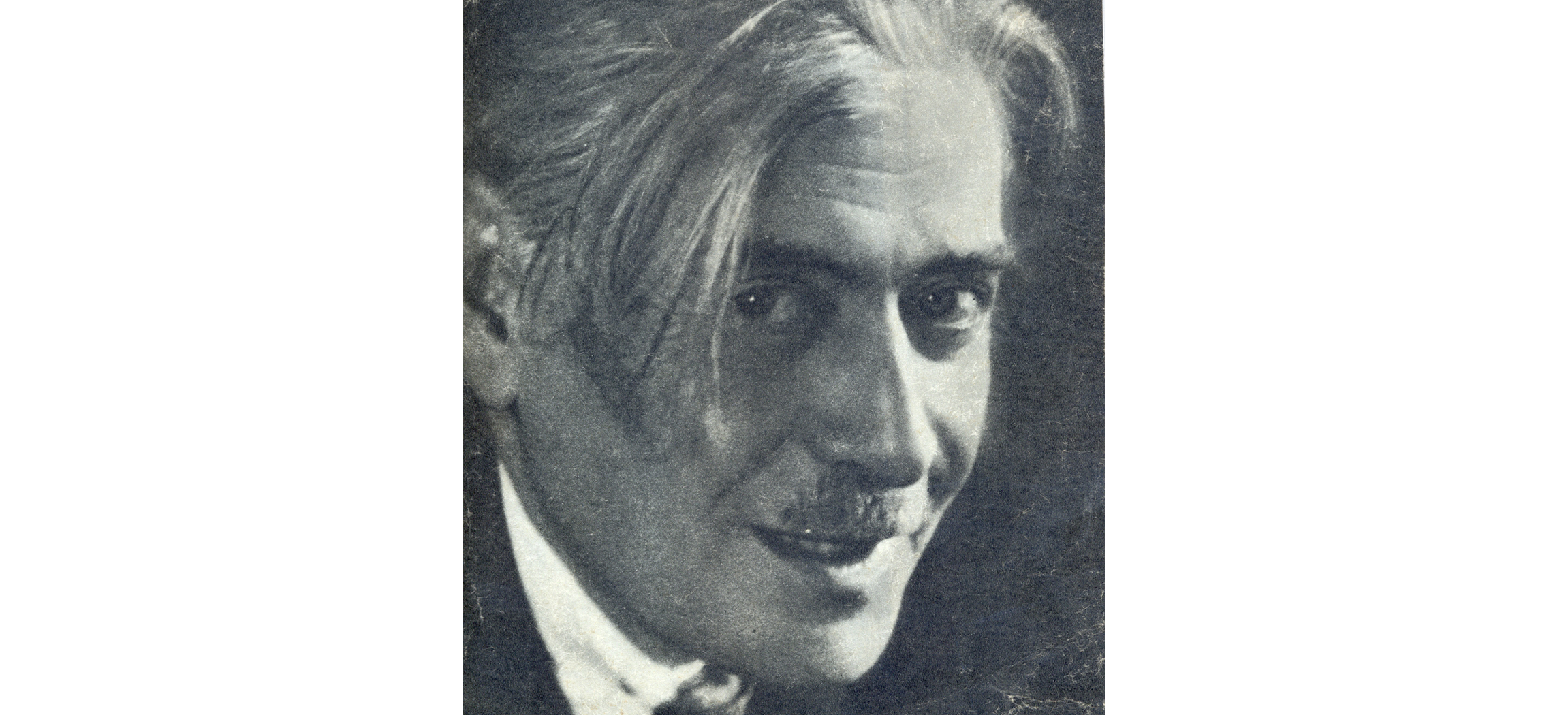

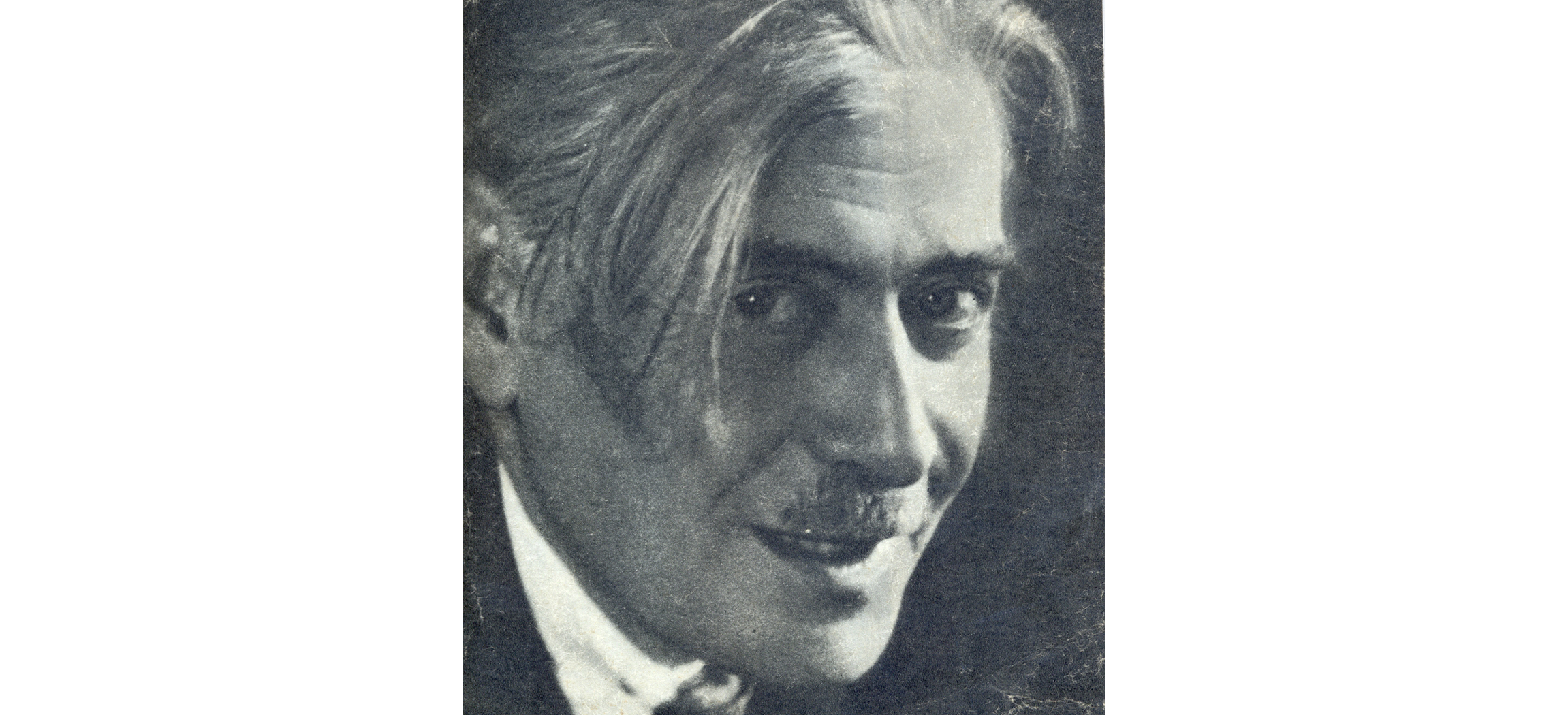

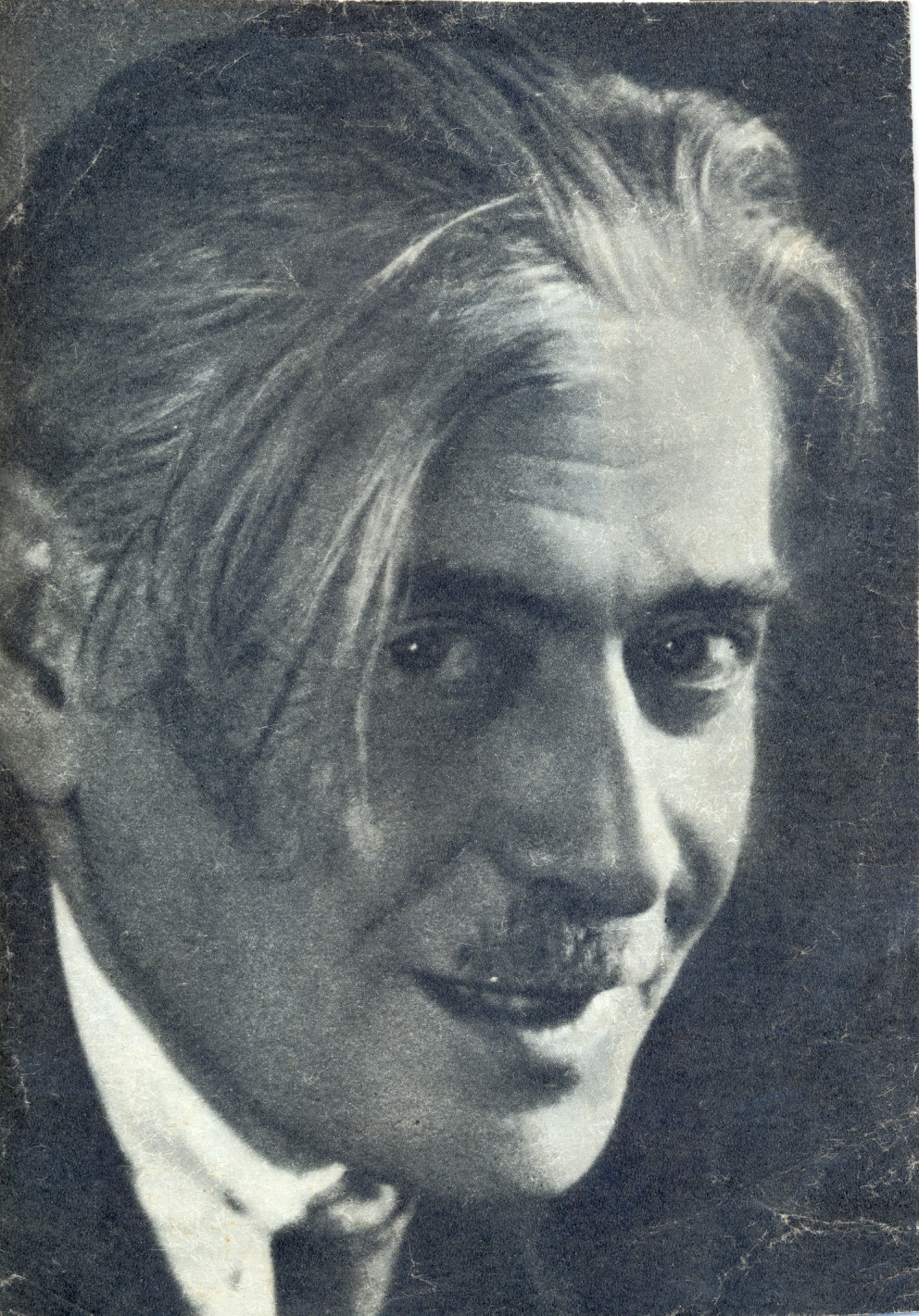

Kote Marjanishvili's artistic journey spanned 43 years—10 as an actor and 33 as a director. He passed away unexpectedly at the age of 61. The ingratitude of his Georgian students, coupled with the constraints of the Soviet system, ultimately led to the demise of an outstanding visionary who played a pivotal role in the evolution of contemporary theatrical art. A true devotee of the stage, Marjanishvili was, metaphorically, “killed” by his unwavering passion for the theater, ultimately succumbing to a myocardial infarction.

Kote Marjanishvili was born in Kvareli to an aristocratic, well-educated family. His father, Aleksandre Marjanishvili, was a poet and translator, and his mother, Elisabeth Chavchavadze, was an erudite individual. Their home served as a vibrant salon, where authors and artists gathered to debate the political and social climate, literature, and art, and to stage amateur performances. It was in this environment that young Kote developed a lifelong love for the theater, participating in family productions from an early age.

Kote Marjanishvili during gymnasium years

Kote Marjanishvili with his mother, Elisabed Chavchavadze

While studying at the Tbilisi Noble Gymnasium, he spent his holidays in Kakheti, where, in Telavi, he would stage plays, and even act in them.

In 1893, he joined the Kutaisi Georgian troupe led by his cousin Kote Meskhi, and, a year later, he appeared on the Georgian stage in Tbilisi before returning to Kutaisi. At the time, the Kutaisi troupe was led by Lado Aleksi-Meskhivili.

In 1898, Marjanishvili moved to the Russian troupe and began touring, acting on stages throughout the Empire.

.jpg)

Kote Marjanishvili

He kicked off his career as a professional director in Riga, Latvia, during the 1904-05 theatrical season, heading theatrical troupes in Riga, Kharkov, Kiev, Odessa, and Moscow. From 1909 to 1913, he served as stage director at the Moscow Art Theater, collaborating with the British theater reformer Gordon Craig on Shakespeare's Hamlet and other notable productions.

In 1913–1914, he founded the Free Theater in Moscow and moved to St. Petersburg, where he led the revolutionary Free Comedy Theater, established the Comedy Opera Theater, and produced several plays in Ukraine.

In 1920, for the Second Congress of the Third International, Marjanishvili organized a large-scale street performance called Towards the World Commune.

Throughout this time, he traveled across European, familiarizing himself with European theater and global theatrical developments. He took note of emerging trends in dramaturgy and the performing arts, and cultivated both creative and personal relationships with writers, playwrights, directors, actors, and artists working in Europe at that time.

In 1913, following his departure from the Art Theater, Kote Marjanishvili founded the Free Theater in Moscow. With its creation, Marjanishvili was working nearly a century ahead of his time, envisioning a unified theatrical space that would merge various art forms: from spoken and non-verbal drama to opera, ballet, pantomime, and operetta. Under Marjanishvili’s direction, renowned directors such as Alexander Sanin and Alexander Tairov collaborated on productions. He had also hoped to invite influential figures like Gordon Craig and Felix Axel Gallen to join the Free Theater. However, these plans were never realized. The theater struggled financially in its first year, and co-founder Vasily Sukhodolsky eventually withdrew his financial backing. As a result, Marjanishvili shifted focus and established a smaller, experimental, studio-based Chamber Theater, which later came under the leadership of Alexander Tairov.

Marjanishvili returned to Georgia in 1922. He was asked to arrange shows by a number of Russian performers, who had a small troupe in Tbilisi. He staged Oscar Wilde's Salome, Metzel's pantomime The Charming Light, and

At the time, Georgian theater was experiencing a profound crisis. In September, during a meeting held to discuss the closure of the Georgian theater, Paolo Iashvili proposed inviting Marjanishvili to direct a play with the Georgian troupe. Initially, Marjanishvili declined, but then unexpectedly agreed, prompting the theater leadership to defer the final decision on the theater's closure until after the premiere.

The modern era of Georgian theater began on November 25, 1922, with Marjanishvili’s production of Lope de Vega's The Sheep Well.

The Sheep Well. Rustaveli Theater. 1922

In the 1923-24 season, as artistic director of the Rustaveli Theater, Marjanishvili invited Mikheil Koreli and Sandro Akhmeteli to join as production directors. Together with others, he established a training facility for actors and directors which later became the Shota Rustaveli State University of Theater and Cinema of Georgia (formerly the Theater Institute). Collaborating with young playwrights, he helped shape contemporary Georgian dramaturgy.

Marjanishvili also introduced a new generation of visual artists, designers, and composers to the stage, including Kirill Zdanevich, Irakli Gamrekeli, Lado Gudiashvili, Elene Akhvlediani, Petre Otskheli (later), Tamar Vakhvakhishvili, Iona Tuskia. He mentored countless directors and performers, many of whom went on to refine their teacher's artistic principles. The next generation learned from him what it takes to be a director, actor, and true artist- Akaki Vasadze, Mikheil Chiaureli, Veriko Anjaparidze, Sandro Akhmeteli, Ushangi Chkheidze, Tamar Chavchavadze, Emanuil Apkhaidze, Veche Jikia, Shalva Gambashidze, and others, among them.

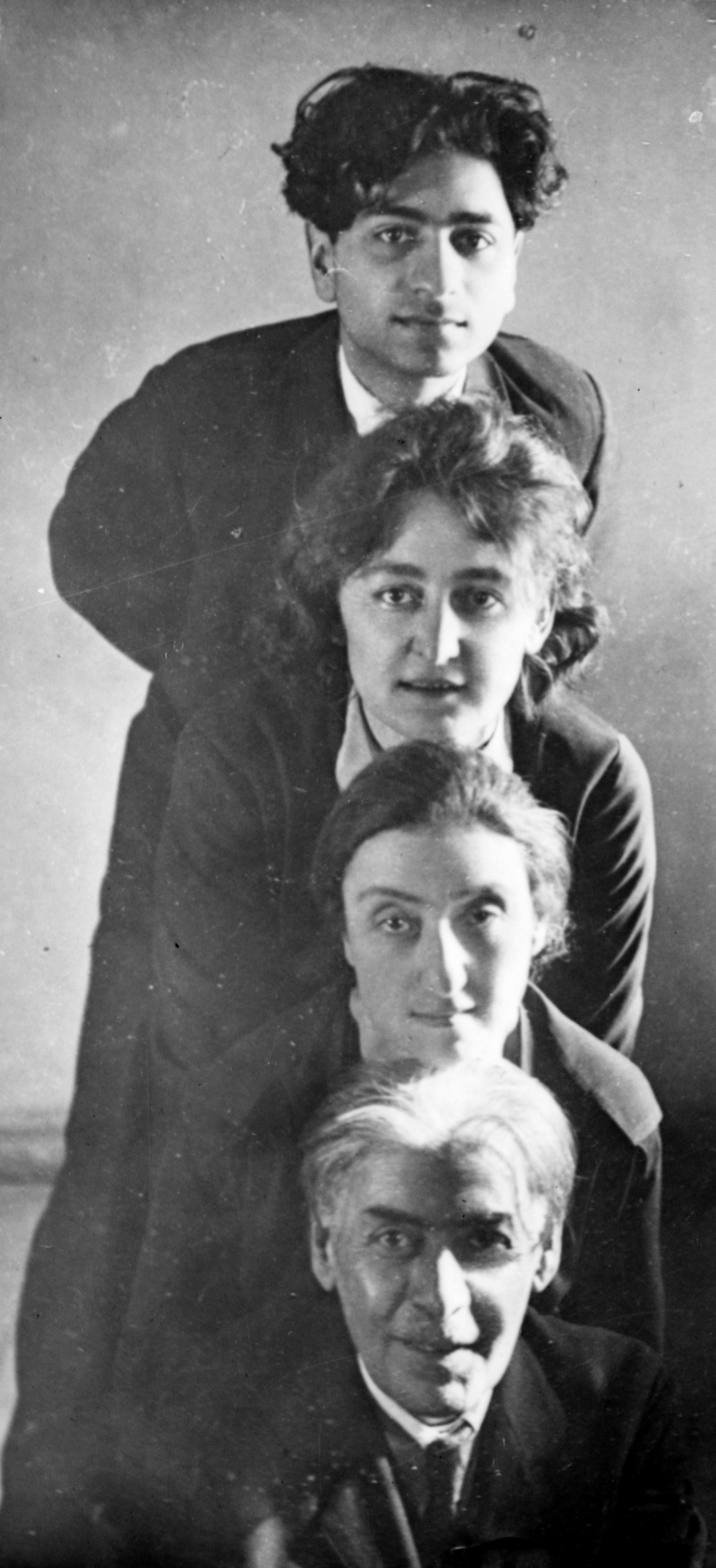

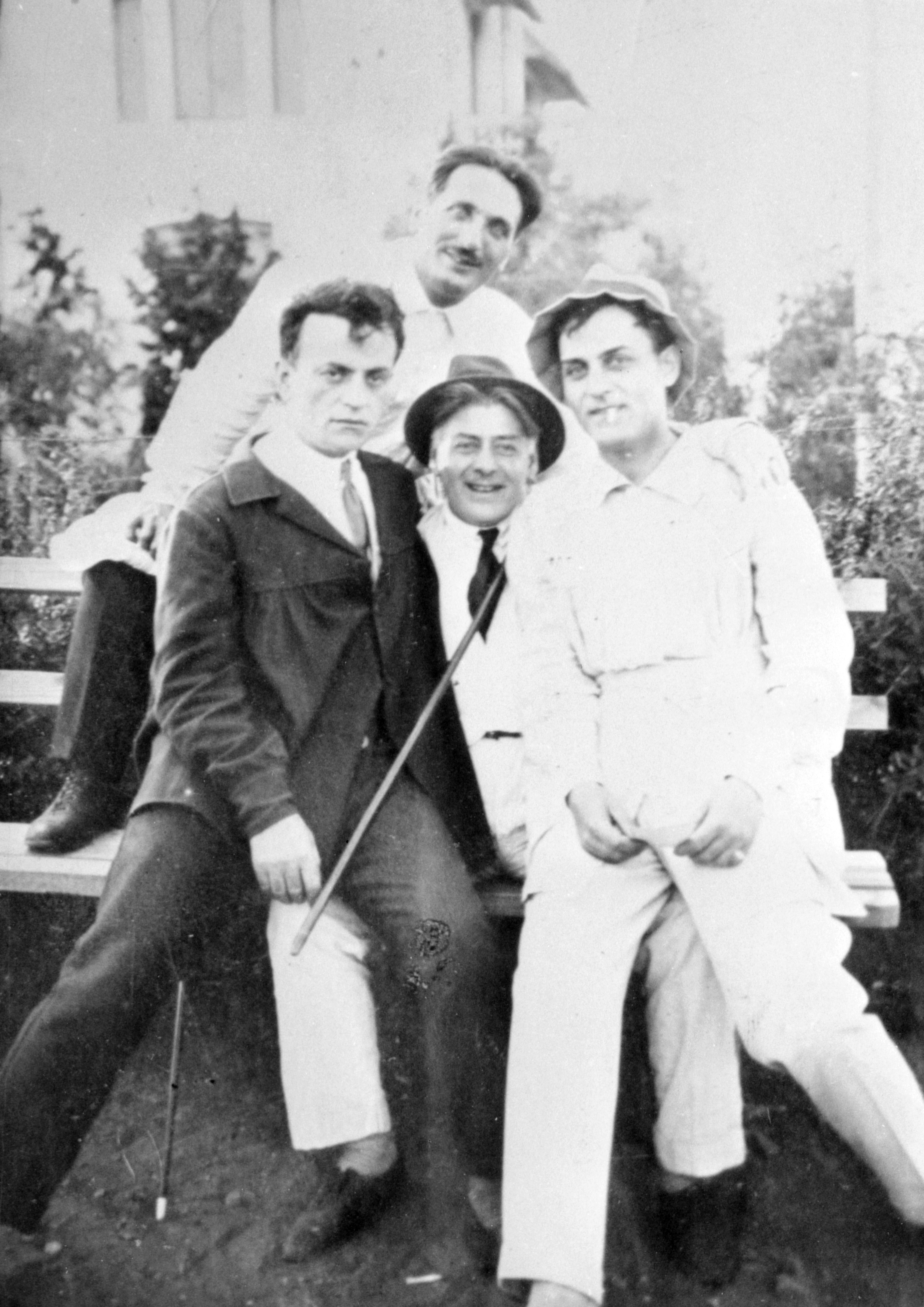

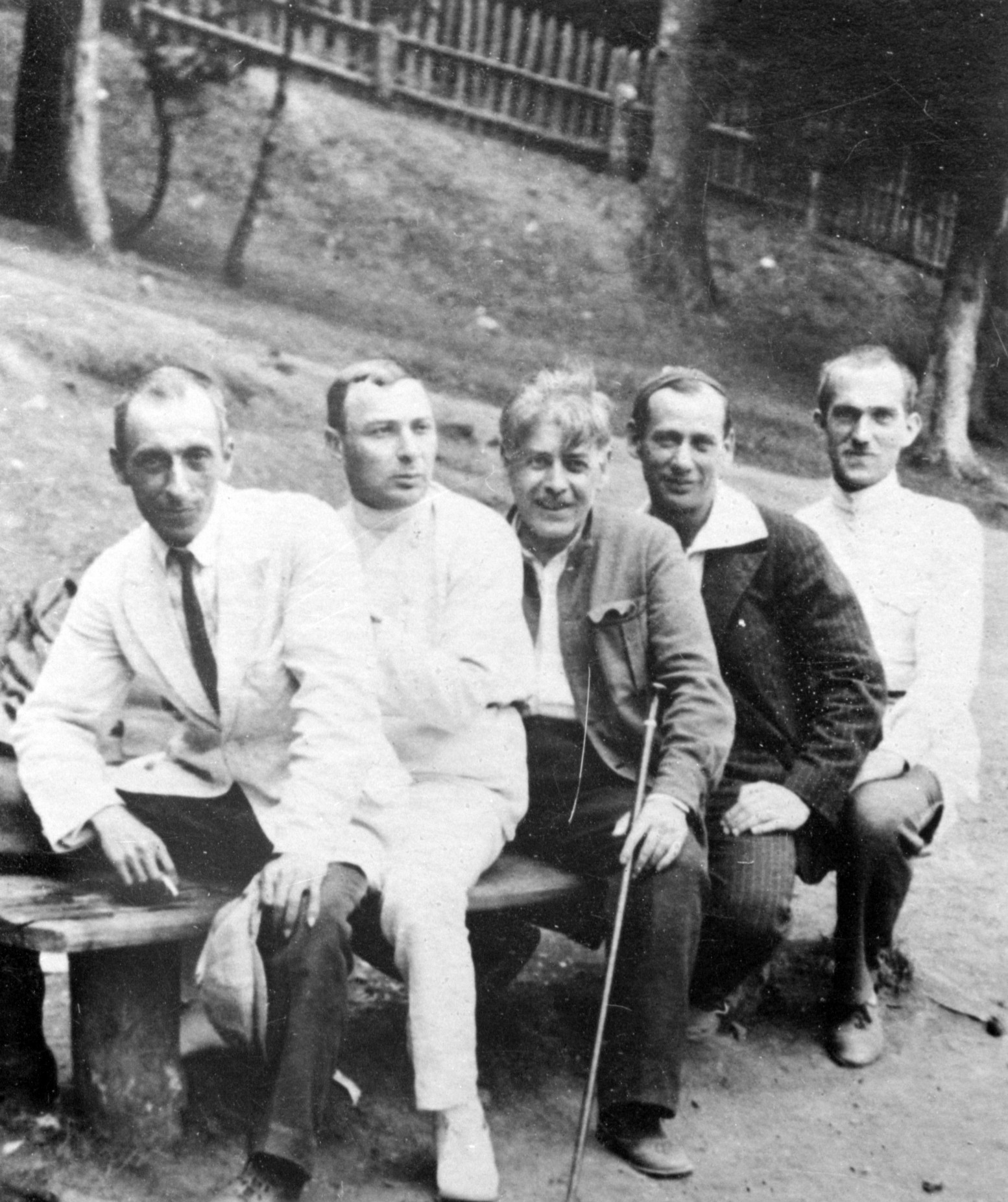

Petre Otskheli, Elene Ghoghoberidze, Tamar Vakhvakhishvili and Kote Marjanishvili

Sandro Akhmeteli, Sandro Shanshiashvili, Kote Marjanishvili and Davit Chkheidze

Valerian Sidamon Eristavi, Ioseb Grishashvili, Kote Marjanishvili, Dodo Antadze

From 1922 to 1926, Marjanishvili presented a rich and diverse repertoire at the Rustaveli Theater, staging works by Georgian and international playwrights, ranging from Renaissance dramaturgy and Romanticism, to works from the Age of Enlightenment, Neo-Romantics, Romantics, Expressionists, and Symbolists.

His productions included Solar Eclipse in Georgia by Zurab Antonov, Divorce by Giorgi Eristavi, Londa by Grigol Robakidze, Mascota by Edmond Audran, The Would-Be Noble by Moliere, The Game of Interests by Hero by John Singer, Malmström (The Man from the Looking Glass) by Franz Werfel, The Funeral of the Whip by Shanshiashvili, Hamlet by Shakespeare, and Lamara by Grigol Robakidze. The last was staged with Akhmeteli, but, due to a conflict Kote refused to sign the playbill.

Under Marjanishvili’s leadership, the Rustaveli Theater became a dynamic center of synthetic art, uniting diverse artistic disciplines into a groundbreaking theatrical vision.

Rustaveli Theater Troupe, 1923

Rustaveli Theater troupe after the premiere of Shakespeare's Hamlet, 1925

Two years later, in 1928, Marjanishvili and his collaborators founded a new theater—the Kutaisi-Batumi State Drama Theater. In 1930, he and his troupe moved to Tbilisi. On this new stage, the renowned director directed several notable plays, including Ernst Toller’s Hoppla, We're Alive!, Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan, Shalva Dadiani’s In the Depth of the Heart, Karl Gutzkow’s Uriel Acosta, and Polikarpe Kakabadze’s Kvarkvare Tutaberi. Between 1930 and 1932, while working in Tbilisi, he also directed Grigol Bukhnikashvili’s Yes, But, Aleksander Afinogenov’s Fear, Shakespeare’s Othello, and other works.

Kote Marjanishvili during making decoration for Uriel Acosta

Among the performances staged by Kote Marjanishvili at the Tbilisi Opera House, the following are especially notable: Dimitri Arakishvili’s The Legend of Shota Rustaveli (1923), Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin (1924), Zakaria Paliashvili’s Abesalom and Eteri (1924) and Daisi (1923), and Rossini’s William Tell (1931).

A director of remarkable creative range, Kote Marjanishvili—who referred to himself as an “illusionary storyteller”—staged works across a wide spectrum of genres and styles emerging in Europe and Russia. As early as the dawn of the 20th century, he was working to fuse verbal and non-verbal theatrical languages. His productions spanned classical and contemporary works, both dramatic and adapted prose, by Georgian and foreign authors alike. He was ever in search of new theatrical forms.

Kote Marjanishvili was the first in Georgia to incorporate cinematic techniques into theater, most notably integrating actual film shots into his production of Hoppla, We're Alive! by Ernst Toller. In addition to his work in theater, Marjanishvili was among the first Georgian film directors. He directed several significant films, including Before the Storm (1925), Samanishvili’s Stepmother (1926), Gogi Ratiani (1927), Amok (1928), The Gadfly (1928), and The Communard’s Pipe (1929).

,_set._მხატვრული_ფილმი__გოგი_რატიანი_._1927._გადასაღები_მოედანი_.jpg)

Feature film Gogi Ratiani (1927)

,_set._მხატვრული_ფილმი__კომუნარის_ჩიბუხი_._1929._გადასაღები_მოედანი_.jpg)

Feature film Komunari Chibukhi (1929)

In the early 1930s, Marjanishvili’s sister Tamar, a nun, was arrested during the Stalinist purges. In a desperate attempt to save her, Marjanishvili made repeated trips to Moscow to appeal to high-ranking officials for her release. At around the same time, his ungrateful students turned against him, forcing him out of the Second State Theater he had founded in Georgia.

Despite these personal and professional blows, Marjanishvili managed to stage three more performances in Moscow: Ibsen’s The Master Builder, Johann Strauss’s operetta The Bat, and Schiller’s Don Carlos. On the eve of the Don Carlos premiere, Marjanishvili once again approached Soviet officials, pleading for help for his ailing sister in exile. Their chilling reply: “Forget that you ever had a sister. And be careful not to get arrested yourself.” The emotional blow proved fatal – on returning home, he suffered a brain hemorrhage and died at the age of 61.

Kote Marjanishvili

Yet his efforts to save his sister had not been in vain. His friends later succeeded in rescuing the tuberculosis-stricken Schema-hegumene Tamar from exile in Siberia, though, sadly, her brother did not live to see her return. Later, in recognition of her devoted Christian service, Mother Tamar was canonized by the Georgian Orthodox Church.

Kote Marjanishvili passed away in Moscow on April 17, 1933. On April 27, the Georgian public brought his ashes back to Tbilisi. Initially, he was buried in the garden of the Opera and Ballet Theater. In 1964, his remains were reinterred at the Holy Mount Parthenon.