Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

It is difficult to find anyone in Georgia who is unfamiliar with Shota Rustaveli’s iconic 12th-century poem The Knight in the Panther’s Skin (Vephistkaosani). The poem recounts the exploits of the main characters, Tariel (who is the knight in the panther's skin) and Avtandil, in their quest for love.

Although the poem is set in the fictional lands of 'India' and 'Arabia,' it reflects the reign of Queen Tamar (1184-1213), a period of Georgian history regarded as a golden era. The poem pays tribute to values such as devoted friendship, love, dedication, heroism, and chivalry. The poem is also deeply philosophical, touching on profound ideas that resonate with readers on a spiritual level. The Knight in the Panther's Skin stands as the pinnacle of Georgian poetry.

Despite its composition in the 12th century, the earliest surviving manuscripts of The Knight in the Panther’s Skin date from the 16th–17th centuries, with around 170 known copies from that era. Among these, the illuminated manuscripts hold particular cultural and artistic significance. The 16th-17th centuries were a turbulent time in Georgian history. Positioned between two powerful Islamic states – the Ottoman Empire and Safavid Iran – Georgia was often subject to their political and cultural influence. These historical circumstances left their mark on nearly every domain of Georgian life and culture, leaving visible traces in everything from literature and art to customs and clothing.

Of all the artistic media, book illustrations – particularly the illustration of secular literature – was most profoundly shaped by Iranian artistic traditions of this period. A major factor in this influence was the active translation of Persian literary works into Georgian, many of which were lavishly illustrated in their original form. These Persian manuscripts served as models and inspiration for local Georgian artists, who adapted their styles, motifs, and techniques.

The so-called Tsereteli Knight in the Panther’s Skin (Vephistkaosani) was copied in the 18th century, while its illustrations date back to the 17th century (S-5006. 33x22 cm). The miniatures appear to have belonged to a manuscript from that period, and it is assumed that the original manuscript was damaged and the miniatures were removed and incorporated into the Tsereteli Vephistkaosani. The Tsereteli manuscript is adorned with full-page miniatures that adhere to the poem's narrative, created by two artists over a short period of time in the first half of the 17th century, and in the 1660s-1670s.

Even a glance at the illustrations demonstrates that the first artist, responsible for 60 of the miniatures, was strongly influenced by 17th century Isfahan miniature painting. His work shows little to no connection with Georgian art, instead closely adhering to the principles of Persian book illumination.

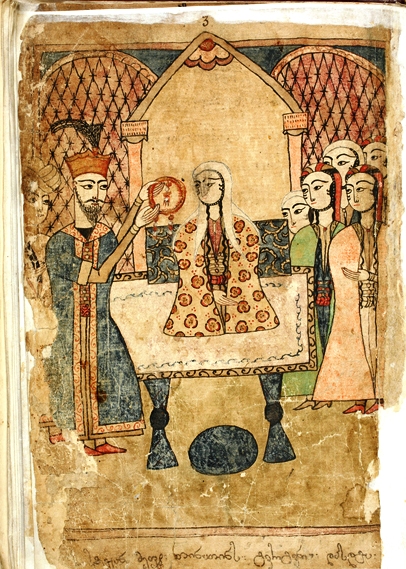

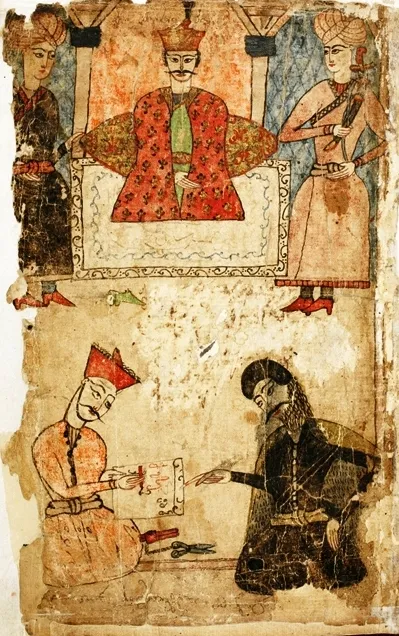

The miniatures illustrate the story, without a nuanced understanding of the poem’s deeper context. The selection of scenes often includes not only key moments, but also minor or less significant episodes. For example, the coronation of Tinatin is shown in two separate images. One miniature displays King Rostevan leading his daughter Tinatin to the throne, and the other shows Tinatin’s enthronement. Inscriptions next to the miniatures explain what is happening in each scene: “Here, King Rostevan leads his daughter to the throne” and “Here, King Rostevan enthrones his daughter Tinatin.”

The Tsereteli Vephistkaosani. King Rostevan leads Tinatin to the throne

The Tsereteli Vephistkaosani. Enthronement of Tinatin.

Like the Iranian miniature paintings, the illustrations of the Tsereteli Vephistkaosani are distinguished by their decorative character. The compositions are symmetrical and balanced, the figures calm; their expressions emotionless. Each element of the composition is rendered with equal care, whether it be a key figure or a small detail, such as a flower or an ornament. The pictorial plane is completely filled with rhythmically arranged elements, giving the miniatures a carpet-like appearance - one of the most characteristic features of Iranian miniature paintings. The pure, bright coloring, contrasting color combinations and virtuoso fineness of the lines also align the Tsereteli Vephistkaosani illustrations with the Iranian miniature painting.

The Tsereteli Vephistkaosani. King Rostevan and Avtandil on a Hunt

The Tsereteli Vephistkaosani. Meeting of Tariel and Avtandil

The Tsereteli Vephistkaosani. Tariel seated by the water

The influence of Iranian art is also manifested in the miniatures executed by the second artist, who was responsible for 26 miniatures. However, artistic features of Georgian painting are also apparent. This artist employed softer color combinations, backgrounds which are less detailed, and figures who are relatively large. Their faces have national features, unlike those created by the first artist, which are marked by the so-called ‘Mongolian type’ characteristic of Persian miniature painting.

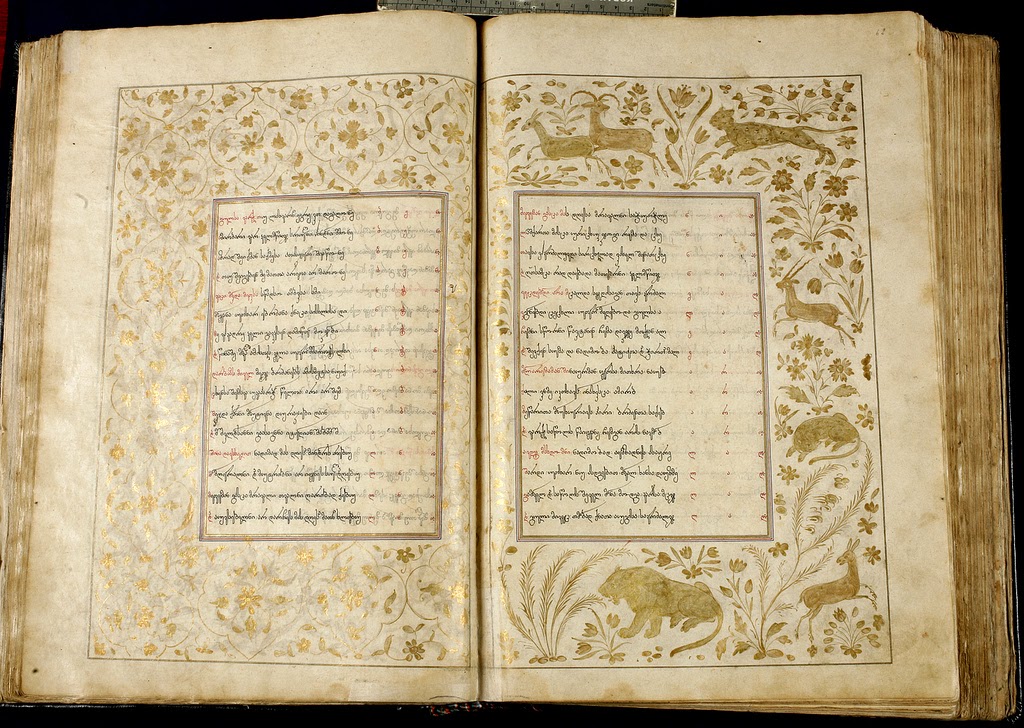

The principles of Isfahan book design follow those of the Vephistkaosani manuscripts copied by Ioane Avalishvili (H-2074. 37x24 cm. 16th -17th centuries) and scribe Begtabeg (H-54. 44.5x30 cm. 1680). Both manuscripts use a decorative framing of the text characteristic of Isfahan book decoration.

The Avalishvili Vephistkaosani

The Avalishvili Vephistkaosani

Yet the influence of Iranian art was not universal: alongside Iranian-style book illuminations, miniatures based on purely Georgian artistic traditions were also produced. One of the best examples of this is the miniatures of The Knight in the Panther’s Skin (Vephistkaosani), copied by scribe Mamuka Tavakarashvili, in 1646, on behalf of Prince of Odishi (now Samagrelo) Levan II (1611-1657). It is the earliest surviving illustrated manuscript of the poem.

Mamuka Tavakarashvili was the secretary to the King of Imereti. In 1634, Levan Dadiani captured him and brought to his court in Odishi. In the colophon, Tavakarashvili mentions that he copied the poem while in captivity.

The Tavakarashvili manuscript (H-599. 27 x19 cm) is adorned with 39 full-page miniatures. Unlike the previously reviewed illustrations, the Tavakarashvili Vephistkaosani miniatures stand as a testament to Georgian artistic tradition. The artist clearly deeply understood the content of the poem, and illustrated the key episodes of the tale.

The Tavakarashvili Vephistkaosani. Enthronement of Tinatin

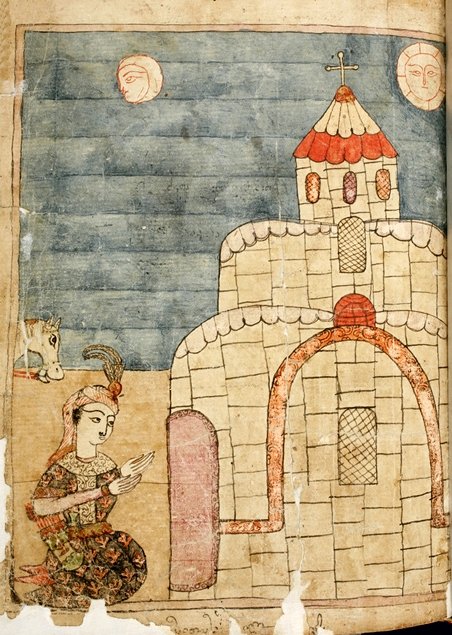

The Tavakarashvili Vephistkaosani. Avtandil praying

The Tavakarashvili miniatures for Vephistkaosani are not characterized by the carpet-like decorativeness of the Tsereteli manuscript illustrations; the artist gives priority to the key characters of the poem, which are distinguished by their large size and positioning in the foreground. The miniatures in question are not of the high level of professional execution, graceful combination of colors, and refinement of lines that are characteristic of the Tsereteli Vephistkaosani miniatures; on the contrary, the figures appear flat and constrained, and the lines are rough and lack plasticity. They are, however, characterized by expressiveness and immediacy.

The Tavakarashvili Vephistkaosani. Tariel

The Tavakarashvili Vephistkaosani. Avtandil

The Tavakarashvili Vephistkaosani miniatures manifest stylistic affinities with the so-called vernacular trend of Medieval Georgian wall paintings. The influence of Iranian art is evident here only in external details, such as the oriental manner of sitting and headgear decorated with feathers and aigrettes.

The Tavakarashvili Vephistkaosani. Meeting of Tarieland Nestan-Darejan

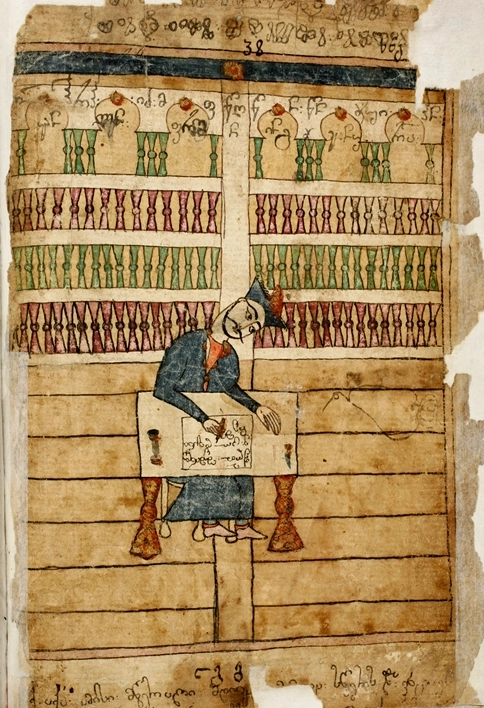

The miniature at the beginning of the book is of particular significance. The upper zone of the composition is occupied by the images of the donor of the manuscript, Levan II Dadiani, accompanied by his entourage. The lower zone features the author of the poem, Shota Rustaveli, and the scribe Mamuka Tavakarashvili. Tavakarashvili is depicted inscribing the poem on a scroll while Rustaveli dictates it to him. It is noteworthy that the artist sees no contradiction in linking figures from the XII and XVII centuries - Rustaveli and Tavakarashvili, depicting them as contemporaries. There are additional miniatures that depict Mamuka Tavakarashvili.

The Tavakarshvili Vephistkaosani. Levan Dadiani, Mamuka Tavakarashvili, Shota Rustaveli

The Tavakarshvili Vephistkaosani. Mamuka Tavakarashvili

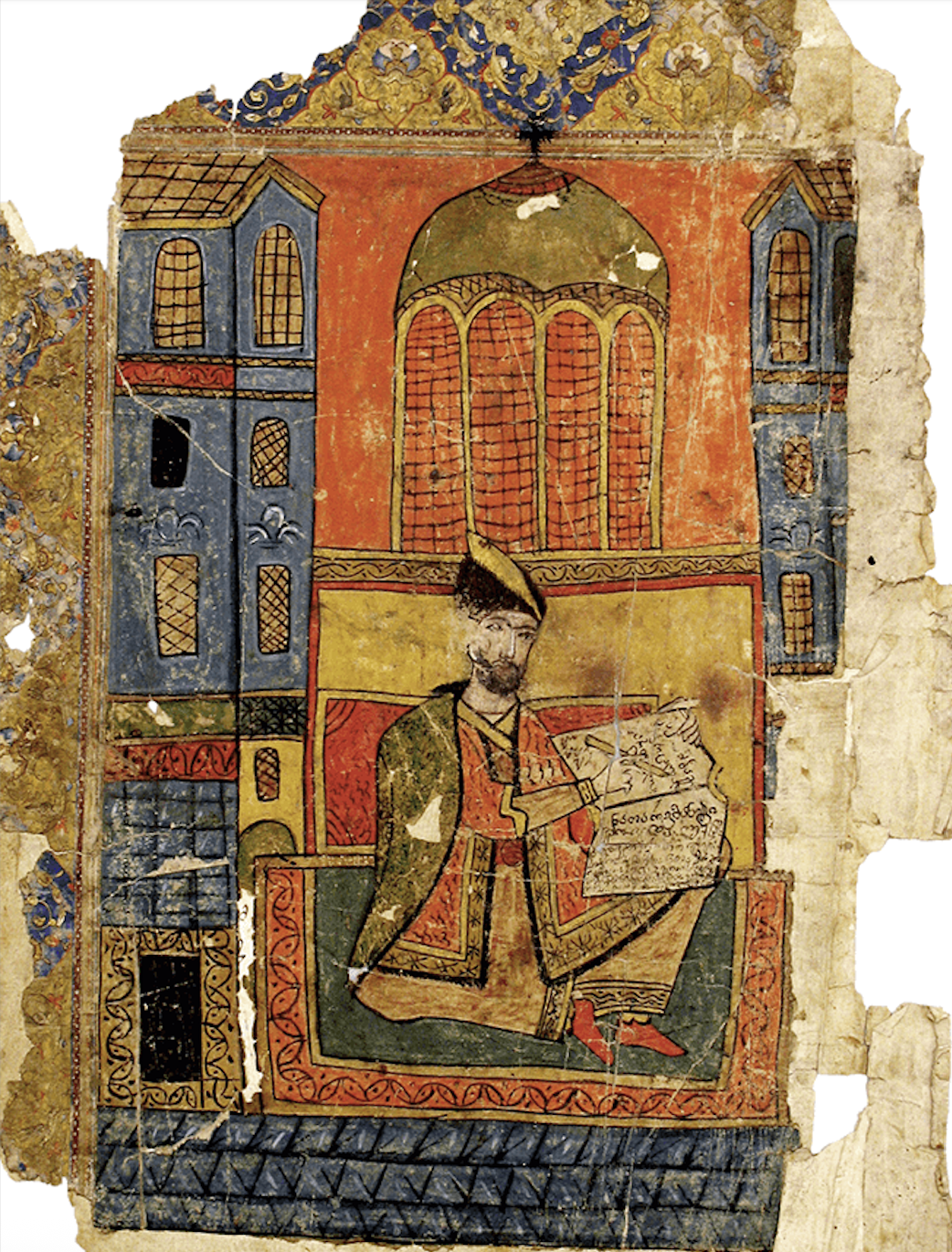

In addition to the Tavakarshvili Vephistkaosani, two other portraits of Shota Rustaveli have survived: a painting from the Jerusalem Holy Cross Monastery (16th century) and a 17th century miniature that is currently housed at the State Museum of Arts. The miniature was originally an illustration of the manuscript of The Knight in the Panther’s Skin (Q-1082), and depicts Rustaveli sitting on a rug with an open book on his lap and a pen in his hand. This is the image which served as a model for the widespread portrait of Shota Rustaveli.

Shota Rustaveli. Miniature

The manuscripts of Shota Rustaveli’s The Knight in the Panther’s Skin that were reviewed here are housed at the K. Kekelidze National Center of Manuscripts. In addition, the Oxford Bodleian Library houses a manuscript of The Knight in the Panther’s Skin from the 17th century, which is similarly adorned with miniatures.