Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

Otar Chkhartishvili was born in 1938 in Kobuleti and spent his early years in Abkhazia. As a child, he would often sit for hours on the shore, gazing out to sea. In his memoirs, he said the experience gave him a profound sense of freedom. The sea and its coastline went on to become recurring motifs in his art.

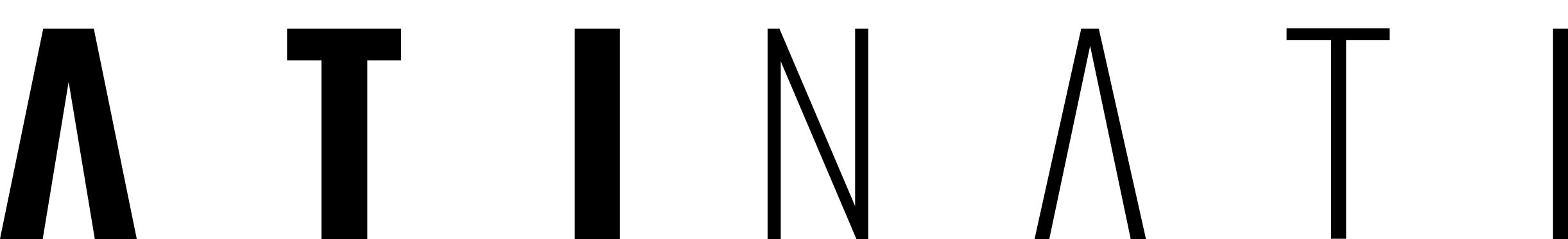

Otar Chkhartishvili. Self-portrait. Canvas, oil. 80X58. 1967. ATINATI Private Collection

In 1960, Chkhartishvili enrolled at the Tbilisi Academy of Arts. The following spring, in 1961, he and a group of fellow artists staged an unsanctioned open-air exhibition on Rustaveli Avenue. While the works displayed at this impromptu vernissage were not particularly groundbreaking, it was through this act that the artist expressed his stance against the Soviet regime. Lado Gudiashvili and Elene Akhvlediani supported the group. Unsurprisingly, the authorities responded with hostility and took retaliatory measures, though the young artists ultimately escaped severe punishment. Despite being expelled multiple times from the Academy, the “rebellious” artist Otar Chkhartishvili was able to complete his studies there.

Otar Chkhartishvili with a portrait of his wife. 1980

A Soviet underground artist, Chkhartishvili produced works that captured the social and aesthetic dimensions of unofficial art. The worldview and visual language of underground artists were radically different from the conventions of socialist realism. Though, by that time, the system had begun to weaken and unravel, it still held significant ideological weight and influence.

Otar Chkhartishvili. Jeans. Canvas, cardboard, jeans, oil. 110x69cm. 1965. ATINATI Private Collection

Underground, or nonconformist, art marked a turning point in the kaleidoscope of artistic developments within the post-Stalin Soviet Union, dramatically altering the trajectory of Soviet art from the 1960s onward. Today, it is recognized as one of the most vital contributions of the 20th-century artistic heritage. A defining moment in this movement occurred in 1974, when Alexander Glazer and Oscar Rabin organized an exhibition in a vacant field in Belyayevo, Moscow. The authorities responded with force, using bulldozers to destroy the artworks, a brutal act that gave the event its name: the Bulldozer Exhibition.

This artistic event stood in stark opposition to the ideological and formal clichés of socialist realism. The artists who participated in it became historical figures of nonconformist art. One of the leading figures of Sots Art, Eric Bulatov, once said: “Our cognition adapts to the distorted space to such an extent that it eventually feels like the norm; however, in reality, it is simply a replacement for actual norms.” This process of normalizing reality, offering an accurate interpretation of events, and freeing oneself from the canonical structures of artistic language, was the goal of the organizers and participants of the famous exhibition, among them the legendary Otar Chkhartishvili.

Nonconformist artists from left: Otar Chkhartishvili, Natalia Abalakova, Anatoly Zhigalov, Larisa Pyatnitskaya, Alexander Glezer, Aleko Goguadze, Alyona Kirtsova. Moscow. 1970s.

Chkhartishvili left a rich and multifacited artistic legacy, encompassing landscapes, portraits, still lifes, collages, assemblages, and objects. Yet, for him, the genre or subject matter were never the central focus—"merely a reason," as he put it. Ultimately, it was through art that he became an active participant in his own inner world, constructing a personal universe shaped by his perceptions, imagination, and attitude toward reality. In his landscapes, the artist conveys the essence of a static, motionless world. The space is often closed, and time seems to have stopped. The horizon rarely appears.

Otar Chkhartishvili. Kvemo Kartli, Spring. Canvas, oil. 61X81. 2002. ATINATI Private Collection

Otar Chkhartishvili. Cypress Trees. Cardboard, oil. 69x66cm. 1985. ATINATI Private Collection

This closed, immobile world is also indicative of the era—the "great achievement" of the Soviet Union, marked by political and creative isolation. The pessimism evident in those landscapes reflects a vision of reality as unchanging, set against a backdrop of ideological and technocratic aggression. As a result, Chkhartishvili’s world seems uninhabited, empty, while the human presence appears insignificant.

His landscapes are free from the ideological constraints, pathos, and didactics that characterized socialist realism. His works stand as a creative act in opposition to these very clichés. This is not a mere trend or formal passion, but rather a profound engagement with reality, and the ability to perceive its deeper essence. This sense of alienation, Chkhartishvili’s decision to exist and create beyond the boundaries of official reality, is what gives his landscapes their haunting, singular power.

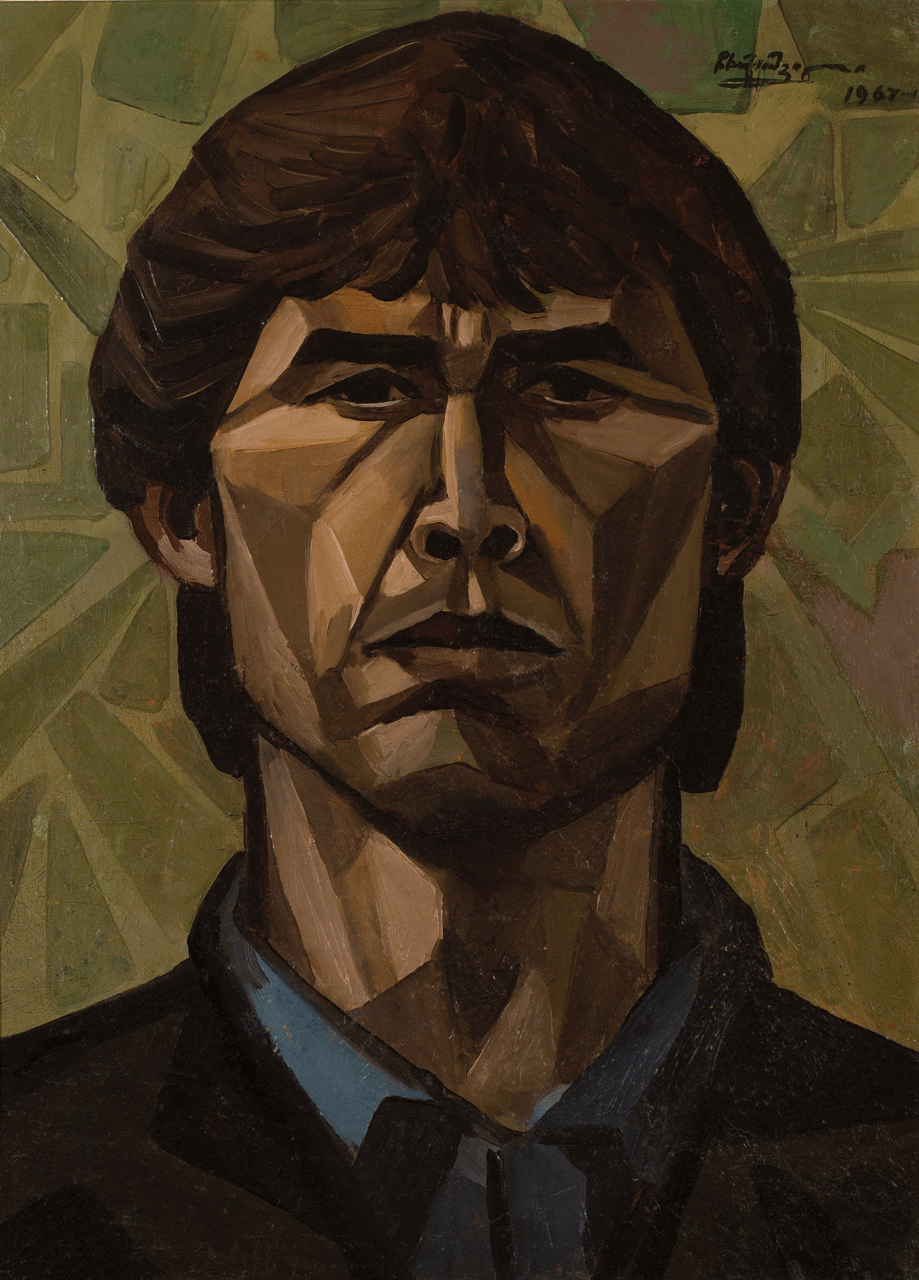

Otar Chkhartishvili. Abstraction on the theme of winter. Cardboard, oil. 40x47. 1984. ATINATI Private Collection

Four Seasons of the Year is a series of paintings born as a result of long-term observation, depicting the same motif: a fragment of a yard seen from the window of the artist's apartment in Rustavi in different seasons of the year. As the seasons change, Chkhartishvili alters both his approach and style of depiction, transforming the realistically rendered yard fragment, along with its atmosphere, mood, and poetic essence, into abstract compositions, through the denaturalization of matter. His works often depict poetic scenes drawn from the rhythms of everyday life, yet his still lifes, in particular, transcend the mundane.

Otar Chkhartishvili. My yard, February. Cardboard, oil. 42x60. 1984. ATINATI Private Collection

Otar Chkhartishvili. My Yard. Canvas, oil. 57x78. 1984. ATINATI Private Collection

Chkhartishvili's work may have started out as a subconscious postmodernist dialog with creative personalities from the past, but it eventually became an artistic approach. Portraits painted in oil are characterized by stylistic diversity. The artist embraces new materials and expressive techniques, yet remains deeply rooted in an understanding of nature and its inherent uniqueness.

Friendly and creative interactions with the leaders of the Moscow and Leningrad underground provided Otar Chkhartishvili with powerful inspiration.

Nonconformist art is a sociocultural phenomenon that emerges from its historical setting. A critical-ironic vision of reality produces a radically distinct adaptation of the creative form, ranging from pop art to new reality. Nonconformists succeeded in decentralizing the canonical, regulated structures of socialist realism. By integrating dogmatic artistic forms and canonical schemes in Soviet art in a new conceptual way, they produced a completely new universe of mood and plasticity, expressing the creative and ideological distinctiveness of the moment.

Marcel Duchamp developed the "artistic strategy" for future art. To oppose the conventionality of society's values and traditional art, he used sarcastic play with ready-made forms of commercial culture, as well as the sacralization of everyday items. Social art creates a grotesque version of the aesthetics of Soviet ideological production, and appeals by ironizing the clichés of ideological art. There is a distinct sense of individuality in Otar Chkhartishvili's social art, which bears broad, conceptual and artistic marks of style. He is the only artist in Georgia whose social art became a full-fledged demonstration of creative integrity.

Chkhartishvili was affected by the ideological environment that surrounded him, particularly by the realities of Rustavi, the city where he lived. After World War II, the city grew almost out of the desert, mostly built by German prisoners of the war. It stood as a showcase of socialist progress, populated by a multicultural workforce striving toward the communist ideal. Its landscape was dominated by factories, towering chimneys, dormitories, administrative buildings, cultural centers, and ever-present political symbolism: monuments to Soviet leaders, massive banners, and ideological slogans. But beneath this curated facade, the contrast between utopian rhetoric and lived reality was clear: a dissonance that left a lasting mark on Chkhartishvili. In his art, this tension was transformed into powerful irony. He didn't simply create new works—he reinterpreted existing ones. Communist symbols and ritual objects—flags, badges, portraits of leaders, state emblems—were removed from their official contexts and repurposed to reveal their absurdity. By putting together pieces of serial Soviet art, an artistic wholeness with completely new ideas was generated. Soviet symbols, mythologized characters of the system and ideology, who guaranteed undefeatable strength and a secure way of life for the country over decades, were replaced by the grotesque. The "ritual act" of incorporating the incompatible in the game is one of the key creative approaches that define the aesthetics of Chkhartishvili's works.

Otar Chkhartishvili. Triptych. The Life of Christ. Dedicated to the Memory of His Mother and Father. Wood, oil. 52X112. 1999. ATINATI Private Collection

Red, with its historical, emotional, and psychological weight, was the color of revolution, blood, fire, and ideological fervor. The hue of blood is associated with passion and strife. It is an aggressive hue, hence many twentieth-century terrorist groups used it as an emblem. Communist ideology thoroughly utilized the power of the color red on the human psyche, which did not go unnoticed by Sots Art artists. As such, the fundamental visual motif of communist symbolism in Sots Art was mostly red.

This relationship (linguistic-artistic-coloristic) has an intriguing formal solution in Chkhartishvili's collection of publications, "CPSU. Complete Works of Lenin." The conceptual adequacy and absurdity of the composition constructed from the collage of the cover of a communist ideological newspaper and a multi-volume Lenin collection are enhanced by the artist's sketches on the cover in broad strokes: a woman dancing in a cafe chantant, the articulation of a leader's hand, a five-pointed star, a cross, a church with a collapsed dome. It represents Chkhartishvili's open position on the falsehood of newspaper information and the utopia of Lenin's teachings. Blood red is employed throughout the works, sometimes as a visual motif and sometimes as a signature. These collages include allusions to Malevich's programmatic works ("Black Square on a White Background" and "Red Square on a White Background").

Otar Chkhartishvili. Girl from Avlabari. Cardboard, oil. 61x58cm. 1979. ATINATI Private Collection

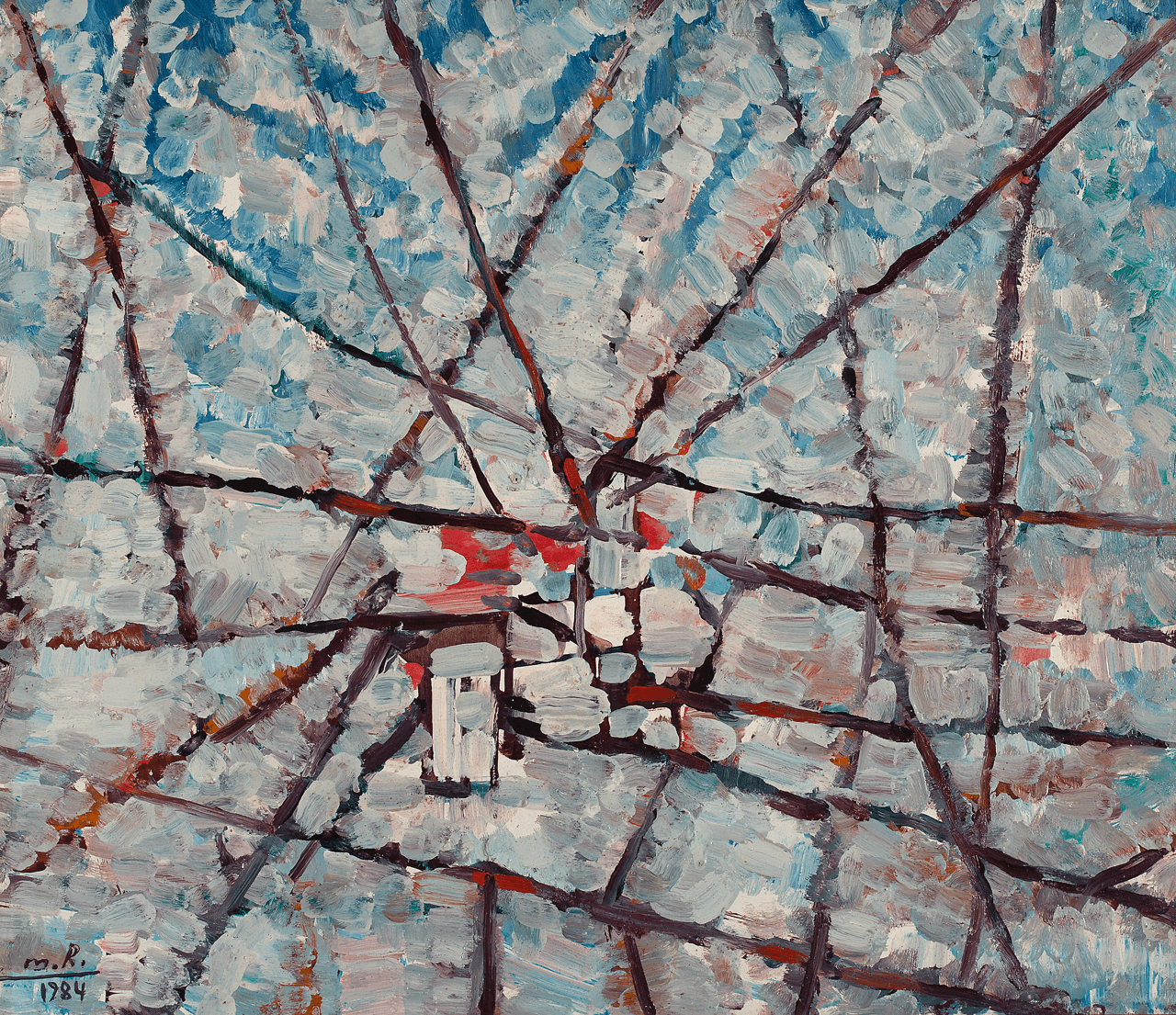

Otar Chkhartishvili’s assemblages—works created by combining painting with diverse objects—convey specific layers of meaning and evoke a wide range of associations and emotions. The artist, as an “archaeologist,” searches for and collects consumer items—Soviet figurative and cultural symbols, pieces from his personal archive, everyday objects, and technical components—which, within his artistic conception, shed their utilitarian purpose and are transformed into signs charged with new significance. The compositions achieve a sense of artistic wholeness, while maintaining a complex internal structure. Each detail, each object, may initially appear to emerge from chaos, yet in reality it is a self-sufficient element within the microcosm constructed by the artist.

Otar Chkhartishvili. Untitled. Plastic, oil, wood, glue. 60.5x69 cm. ATINATI Private Collection

Otar Chkhartishvili faced numerous obstacles throughout his life, yet he played a pivotal role in establishing a postmodernist worldview within Georgian art. His artistic language, at the time often misunderstood and even met with hostility, was rooted in the rejection of Soviet ideological and aesthetic clichés, and the pursuit of a new, free artistic system grounded in exploration and discovery. Reflecting on his path, the artist wrote in his memoirs: “For thirty years, I firmly stood by my position and never betrayed it for a moment… My creativity was, above all, a weapon against totalitarianism and atheism, which I wielded with great love, because it was my duty to do so, and no one else could express what I had to say…”