Feel free to add tags, names, dates or anything you are looking for

When Avto Varazi was first introduced to the writer Guram Rcheulishvili, Guram told his friend of his new acquaintance as they were saying goodbye: “This man is really a true artist.” Rcheulishvili, an outstanding writer, had recognized a kindred spirit in Varazi. Indeed, the word “true” perfectly captures Avto Varazi’s personality, as expressed in his art.

Avto Varazi, photo by Henri Cartier-Bresson. From the book Avto Varazi

You might agree that, in the context of Georgian art, the label “real” or “true” can only be applied to an artist like Niko Pirosmani, who was devoted to painting with heart and soul. Perhaps that’s why Avto Varazi so perfectly performed as that artist in the feature film Pirosmani (directed by Giorgi Shengelaia), which won numerous international awards. The film’s artwork also belongs to Varazi.

Photo of Avto Varazi as Pirosmani

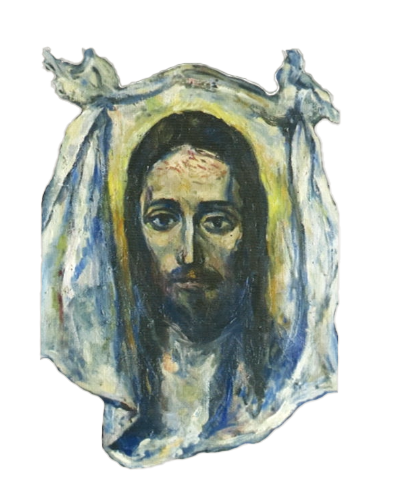

Avtandil (Avto) Varazi was born in Tbilisi on October 25, 1926. He and his brothers, Vakhtang and Levan, were born to well-known parents: their father, Vasil Varazashvili, was a biochemist and pathophysiologist – an internationally recognized scientist who was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1939 (he withdrew the nomination himself out of fear of the repressive Soviet regime). Their mother, Elizabeth, was a noble and virtuous woman with a natural talent for drawing. The family had an extraordinary home library and actively supported the well-rounded development of their children. Avto’s innate artistic talent and love for painting did not go unnoticed by his mother, who made every effort to foster it. He began studying drawing with artist Leonid Potapov, and later studied painting under Alexander Bazhbeuk-Melikov. At the age of 13, the young artist made illustrations for Mikhail Lermontov’s poems Demon and The Novice, earning him the second prize at the All-Union Competition for Illustrations of Lermontov’s Works in Moscow. Unfortunately, these early works did not survive. From an early age, the young man, inclined towards the Christian faith, painted images of the Savior in the style of El Greco.

Avto Varazi. The Saviour. Oil, canvas. 60x43,5cm. 1972. Private Collection

One such surviving piece is the biblical scene The Adoration of the Magi, drawn in Indian ink. In it, the fluid, expressive contour lines that define the figures give way to dynamic stair-like forms – bold, ascending strokes that lead upward to the Virgin Mary and Child, approached by the Magi bearing their gifts. Even in this early, spontaneous sketch, one can see the artist’s remarkable ability to generalize meaning and control inner emotions – qualities that define his artistic style.

Avto Varazi. The Worship of The Three Wise Men. Diluted Indian ink, brush, pen, paper. 12x15cm. 1943. Private Collection

Avto Varazi. Sketches for the Archaeological Exhibition, 1959

Once Varazi fully committed himself to free painting, his creative work can be roughly divided into three periods: 1. The 1950s, from which only a few works have survived; 2. The prolific 1960s, marked by significant works – portraits, still lifes, pop art pieces, and collages – that introduced a new style into Georgian art of that time, and; 3. The challenging 1970s, when he battled a worsening illness (alcoholism) over the course of seven years, a struggle that ultimately ended with his passing away on March 3, 1977. Despite the hardships of his final years, Avto Varazi still managed to create several important works, leaving behind a lasting legacy.

Avto Varazi was unlike anyone else, though many tried to imitate him. Like the anonymous masters of the medieval era, he would work on a particular theme for an extended time, developing multiple variations around a central motif. He painted according to his mood, as if he sought to breathe life into each piece. His inspiration came from subjects that resonated deeply with him, among them musical instruments, especially his favorite violin.

Avto Varazi. Violin. Mixed media. 1970's

It is especially remarkable that Varazi, whose career unfolded under the Soviet regime, never compromised his artistic integrity. He completely rejected the ideological constraints of socialist realism and its poster-like pathos. Guided by a strong creative instinct, he discovered those popular artistic trends that nourished modern Western art. The cultural thaw of the post-Stalin era, which loosened the grip of the so-called “Iron Curtain”– if only slightly – opened a window for artists like Varazi. That is why pop art and collage techniques boldly entered his work, going on to become established within Georgian painting through his unique style. Varazi’s painting foreshadowed the advent of postmodernist painting in Georgia. And yet, despite his innovative explorations, Varazi, much like the Georgian avant-garde artists of the 1920s David Kakabadze, Lado Gudiashvili, Shalva Kikodze, Elene Akhvlediani, Ketevan Maghalashvili and others, retained the distinctive features of national artistic traditions and blended them masterfully with European modernism. His works depict spirituality and a kind of pantheism, along with a harmony between detail and overall composition that balances decorative elements and monumentality, emphasizing linearity and often treating the pictorial surface with a certain relief-like structure. These qualities form a continuous chain of heritage stretching back to the Middle Ages, a tradition that even the pressures of Soviet ideology could not break. This deep cultural legacy subtly surfaced in all stages of Varazi’s creative work. At the same time, the inner tension in the structure of his collages seems to reflect an effort to deconstruct and reinterpret the contradictions of daily life under Soviet regime – fragmenting it into symbolic visual forms.

Avto Varazi. Still Life with Bottles. Oil, canvas and collage. 52x36cm. 1965. ATINATI Private Collection

One of the most striking aspects of Avto Varazi’s creative process is his metaphorical thinking and the presence of symbolic imagery. Among these, a notable motif is the image of a fish, which appears repeatedly in his still lifes and collages. This Christian symbol representing Christ has varying weight in the artist’s works: the relationship between the sign (the fish) and what it signifies (Christ) shifts across different compositions, yet it consistently evokes a sense of the sacred, the transcendent. As Varazi himself once wrote, it speaks to “a sensitive eye and a heart that can perceive.” His still lifes featuring fish, painted over the years, engage with a wide range of emotional tones. At times, the symbolism is purely aesthetic; at others, it resonates with deeper philosophical meaning. For instance, the depiction of a fish skeleton conveys a somber, almost tragic atmosphere, but his images of fish on a plate – heads down, eyes bulging or replaced by hollow voids – is horrifying.

Avto Varazi. Fish in an Openwork Frame. Oil, plate, fish meal, newspaper, plaster, cardboard. 42x61,5cm. 1966. ATINATI Private Collection

Avto Varazi. Composition with Fish. Oil and mixed media (newspaper, sawdust, labels), plywood. 80x55,5cm. 1967. ATINATI Private Collection

For Avto Varazi, as for Niko Pirosmani, the color white carries deep symbolic meaning –representing the embodiment of chastity, spiritual purity, and inner cleanliness. This interpretation of the color white is reflected in others of Varazi’s portraits and still lifes.

Avto Varazi. Still Life. Oil, wood, canvas. 43x63cm. 1975-1976. ATINATI Private Collection

Avto Varazi’s unique works of pop art, particularly those featuring a bull, lamb, octopus, and other animalistic artifacts, are worth spotlighting. These pieces emerged almost spontaneously – assembled from everyday objects like clothes draped over a wall or tossed casually on the floor (including his own paint-stained trousers), worn-out shoes, or random piles of nails scattered across a table – in Varazi’s imagination, these items became associated with different animals or creatures. These quirky, surreal expressions of pop art, born from the artist’s unique vision, now belong to prominent nonconformist collections in both America and Europe.

Avto Varazi. A Horse Head. Oil, trousers, finish lime, sawdust, wood. 1966. Zimmerli Art Museum, USA

The artist's fascination with wooden frames of various shapes, ranging from rigid geometric forms to the contrasting elegance of gold-plated frames, with avant-garde artistic forms inserted into them (such as the skeleton of a white fish as a symbolic concept), raises an intriguing discussion. Remarkably, under the constraints of the Soviet regime, Varazi had the boldness to “play” with stylistic frameworks across different historical periods, sometimes even inserting emptiness within them. In doing so, he elevated these eclectic, simulacrum-like constructions into powerful works of conceptual art.

Avto Varazi "With The White Fish"

In early 1977, Avto Varazi began working on what would be one of his final still lifes – a piece he, sadly, never had the chance to finish. Immensely simple, the composition features just three objects, and is rendered in his favorite palette of bluish-green and yellowish-brown. Yet, despite its minimalism, the painting draws the viewer into the quietly enigmatic visual space, evoking a sense of infinite, unresolved completion – a kind of non-finnito. As the final chord of Varazi’s creative journey, this still life secures his place in the history of Georgian art as a profoundly original artist, fully immersed in his painting, body and soul.

Avto Varazi. Unfinished Still Life. 1977